By Arthur Neslen

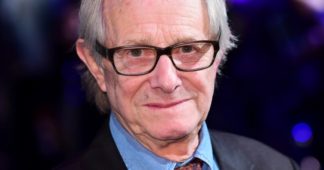

Ken Loach is one of the most influential filmmakers of his generation. His films have won the Cannes Film Festival’s Palme D’or – twice – and its Jury Prize three times, both joint records. Loach’s work has also been honoured at the BAFTAs, and at the Berlin and Venice film festivals.

Over a career spanning more than 50 years, the British film director has been a passionate advocate for socialism, and a dedicated teller of working-class stories. His latest film, The Old Oak, relates a tale of Syrian refugees arriving in a former mining town in the UK’s north-east. It will be released in 2023. In this wide-ranging interview with Equal Times, Loach covers topics including the challenges of organising workers in today’s film industry, the British mainstream media’s “absolutely shameless” attack on Jeremy Corbyn and why, at the age of 86, Loach has no plans to stop making films just yet.

Why did you first want to become a filmmaker? Was there a particular movie that inspired you?

The Italian neo-realists put the workplace on the screen and they were a big influence to begin with. The films set in the north of England in the late 1950s, early 1960s played a part. But the films that made the biggest impression on me were the Czech films of the 1960s – Miloš Forman and Jiří Menzel and those lovely, humanely observed films in which you were just drawn in and warmed to the characters and smiled with them, understood what was happening. I think I took a lot from that and it was a springboard to think about all the technical aspects of filmmaking.

Really though, I was much more interested in the theatre when I was young. We lived in Warwickshire near Stratford-upon-Avon [where the world-famous Royal Shakespeare Company is based] and I used to go to watch the plays and great actors of the time. I was really stage-struck and took every opportunity to read plays and to perform with a group of kids at school.

What was it about the theatre that captured your imagination?

It was the whole experience: the excitement of the live performance, the language, the emotional commitment, and living in a different world of the imagination. When I left university, I’d read law but – much of to my dad’s dismay – I went into the theatre as an understudy in a revue in the West End. I got jobs as an actor – not many – and worked as a supply teacher for most of the time. I was taken on as a director by the BBC, when BBC Two was expanding.

My huge stroke of good luck was being part of a group that produced The Wednesday Play, which had a brief to make contemporary fiction. It was prime-time television. There were only two and a half stations then, so the nation watched if it was of interest. Our brief was to be challenging so it was like a dream. The production was like the theatre in that there were huge studio sets with cameras. But we wanted to be on the streets, creating something in the middle of real situations and we managed, in rather cheeky ways, to subvert the system.

Is there an organic link between socialism and filmmaking?

Filmmaking as a medium can do anything. It’s like the printed word. You can write novels, pamphlets, factual books, opinion. It’s like: how wide is a library? In those early years we developed a sense of politics because the sixties was a very political period and as the New Left developed, one of its slogans was ‘Neither Washington nor Moscow’.

That was the slogan of the International Socialists…

Yes, it was anti-Stalinist and anti-capitalist. After that we read the books and learned our politics and tried to understand how the world works. At the same time, we tried to find ways of telling stories that revealed [what we’d learnt]. The word ‘politics’ sounds rather narrow. The continual thread has been the link between the way people behave, their relationships and their choices – deeply personal choices maybe – and how that is determined by their social and economic contexts.

Which of your films are you most proud of in that respect?

I couldn’t say really. Pride isn’t a healthy feeling. It’s like your children. The ones you [most] care for are the ones that are the least successful – or seem to be.

Are there any films that, in retrospect, you feel were incomplete?

No, because each one is of its time. Filmmaking is the art of the possible. It’s not like writing where you control every dot and comma. It’s what you can get on that day, in that weather, with that group of people, having worked very closely with the writer, whose work is the foundation of the film. The writer is the prime creator – not the director – and it’s what you can get when there’s a thunderstorm in the middle of [filming] or someone’s late or hasn’t turned up. There are lots of things that can go wrong.

What do you see as the biggest challenges currently facing workers in the industry?

It’s very casualised and finances are often very insecure. Youngsters coming into the business are ripped off. They’re asked to work for nothing to improve their CV or get experience, and of course that’s just a way of employers getting free labour. The broadcasters that still support films now subcontract almost everything. But the money given to production companies is inadequate to provide a proper crew, or union rates and so on. That’s a big problem, particularly in documentaries. We need a good union. Our union [BECTU] is now part of Prospect, and that’s been very unsatisfactory.

What have been the problems?

The senior figures in Prospect don’t really understand how our industry works so there’s a constant battle and, as has happened in many unions over the years, the rank and file have different needs to the ones that the officials say they’re trying to resolve.

You’ve made films about this in the past, which have been censored. Is self-censorship now a bigger problem, in terms of what studios will invest in: blockbusters and special effects above narrative?

I think that’s always been the case. It’s a conflict between a commodity and a communication. Investors want commodities and if they take a chance, it’s on something that appeals to them. There’s the old idea that when times are hard, films should be a distraction not an investigation into what’s really going on.

The broadcasters also play a very significant propaganda role. The BBC is a prime example and ITV [the UK’s oldest and biggest commercial network] generally follows suit. One of the clearest examples was the [1984] Miners’ Strike. The line the BBC pursued was “picket-line violence”. That was all you heard about, while everyone that was involved saw police violence, and that of course has emerged.

The other significant event was the destruction of Jeremy Corbyn’s leadership [of the Labour Party, from which Loach was expelled as a member in 2021 for his support of other expelled Corbyn supporters] and the BBC played a prime role in that – an absolutely shameless role – and now that whole political project, that nearly became the government three years ago, has been wiped out of the public discourse.

Has it been delegitimised?

Yes, they’ve rewritten history so that it doesn’t exist. It’s like the photograph of Trotsky that Stalin cut out. The man doesn’t exist in history. Jeremy Corbyn doesn’t exist in history now [either], and all the purges [of the Labour party], the manipulation of the rules and the straight aggression has been unbelievable. It should be unbelievable: the manipulation of rules against the left, the imposition of candidates, expulsions and the fact that at least 200,000 people as far as we know – and probably more – have left the Labour party under [the current Labour leader, Keir] Starmer. It’s not even a news story! If ever we needed a clear example of political manipulation by the broadcasters, there it is. And of course, the Guardian is a joint [offender] in that as part of the liberal media, when those two [media] lead the silence on this extraordinary story, then of course the right-wing press will make the most of it.

You’re still making films at 86. What keeps the fire in your belly?

It’s a privilege. Why would you give it up? The struggle continues. Obviously, there comes a point where your faculties decline – that happens to everyone – and your memory isn’t as good. Everybody who reaches their mid-eighties knows what happens. But you just keep pedalling as far as you can.

Noam Chomsky’s still going strong and he’s ten years older than you…

Well, he’s remarkable but he’s set the bar very high. I’m not sure I’ll get that far. Mind you, I love Noam, I respect him – he’s a lovely man – but I doubt if he, at his age, has ever stood in an Irish bog [while filming the 2014 film Jimmy’s Hall] with his feet wet, early in the morning, thinking: “Why am I here?”

What advice would you give to a filmmaker starting out today?

Get a job in the business. Earn your living at it somehow. Join a union, even though we’ve got to change them, and get to know people. Make friends. Be good. Turn up early. Work as a pro. If you want a craft, then you need to learn a specific amount of technical knowledge but… if you look at films you like and think, “How could I have done that?”, then you can learn most of it.

Do you feel there are still things you need to say in your movies?

Yes! There are so many things but whether I will get another feature film made, I don’t know. I think that’s open to question now.

Are there any hints you can give about the current project you’re working on?

No, I’d rather not. We did two films in the north-east: I, Daniel Blake and Sorry We Missed You and it’s a third one to make it three. But the problem [with hints] is that you set up false expectations. It’s nicer when an audience just walks in, sits down, and doesn’t know what to expect.

We remind our readers that publication of articles on our site does not mean that we agree with what is written. Our policy is to publish anything which we consider of interest, so as to assist our readers in forming their opinions. Sometimes we even publish articles with which we totally disagree, since we believe it is important for our readers to be informed on as wide a spectrum of views as possible.