By Thomas Scripps and Laura Tiernan

27 February 2020

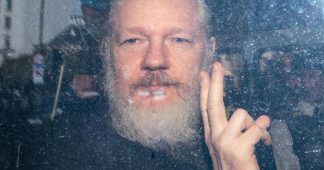

WikiLeaks editor Julian Assange issued a defiant protest in court yesterday, opposing the flagrant abuse of his fundamental legal rights in extradition proceedings brought against him by the United States government.

Assange spoke from the dock on day three of extradition hearings at Belmarsh Magistrates’ Court. The multi-award-winning journalist has been charged under the Espionage Act and faces 175 years in prison for exposing US war crimes, illegal mass surveillance and torture.

Incarcerated at Belmarsh maximum security prison for nearly 12 months in virtual solitary confinement, Assange is being held in violation of international law that prohibits torture and arbitrary detention. He is incarcerated at Belmarsh solely on remand.

At the start of proceedings yesterday morning, District Judge Vanessa Baraitser informed the court that Assange was “medicated” and might have “difficulty following proceedings.” Just after 2.00 pm, she asked Assange’s lawyer Gareth Peirce whether her client was able to concentrate or needed a break.

Rising from his seat in the dock, Assange approached the bullet-proof glass panels separating him from the body of the court, telling Peirce in evident distress that he was under constant surveillance by prison guards, “I cannot communicate with my lawyers or ask them for clarifications without the other side seeing.

“The other side has about 100 times more contact with their lawyers per day… What is the point of asking if I can concentrate if I cannot participate?”

Assange, who has struggled to hear proceedings for much of the past three days, told Peirce, “I’m as much a participant in these proceedings as I am a spectator in Wimbledon.”

Assange’s intervention provoked undisguised hostility from Baraitser. She declared that Assange had no legal right to address the court unless he was testifying, calling a brief adjournment. When proceedings resumed, Edward Fitzgerald QC indicated he would make an application for Assange to sit with his legal team.

Fitzgerald’s unexpected request paralysed Baraitser, who appeared like a marionette with cut strings left dangling. “Do I have the jurisdiction to issue such an order?” she asked James Lewis QC, after he indicated the prosecution would be “neutral” in relation to Assange’s request that he be removed from the dock. Perhaps he could be handcuffed to the desk, Lewis suggested.

“It puts me in a difficult position with regard to the assessment of risk,” Baraitser told the court, with Fitzgerald replying, “We respectfully submit he is a gentle man of an intellectual nature and there’s no reason he shouldn’t be able to sit with us.”

More confusion followed, with Baraitser querying whether the defence team’s request amounted to an application for bail—a suggestion that was immediately shot down by Lewis, who told Baraitser he would undoubtedly object to any bail application. He would need to take instruction on the matter overnight, he told the judge.

The surreal exchange highlighted the legal no-man’s land into which Assange has been thrown. Fitzgerald is scheduled to make an application to the court for Assange’s removal from the dock by 10.00am today.

The outrageous show trial being staged by British authorities has elicited not a word of protest this week from Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn or his shadow chancellor John McDonnell. Appearing yesterday in Prime Minister’s Questions, Corbyn focused on the government’s response to the UK floods, saying nothing about the fate of the world’s most famous political prisoner being decided ten miles away.

After a brief pose of opposition to extradition, McDonnell declared last week that Labour would be constrained in raising Assange’s plight by the sub judice rule. This is a convenient excuse for political cowardice and duplicity. Had he chosen to do so, Corbyn could have spoken out against the brutal treatment meted out to Assange every day this week and demanded his immediate release whatever the consequences.

Legal arguments yesterday focused on the UK-US extradition treaty. Assange’s defence team argued that the 17 charges against him under the Espionage Act (and a separate charge of computer crime) were “pure political offences.”

Fitzgerald told the court, “This is about policy in Guantanamo, policy in the Iraq war, policy in the Afghan war, loss of civilian life, torture and war crimes.”

Article 4 of the Anglo-US Extradition Treaty states that “extradition shall not be granted if the offence for which extradition is requested is a political offence.” It should therefore bar Assange’s extradition for the espionage conduct alleged.

However, the prosecution claims that since this specific provision of the treaty is not incorporated into English law, it is irrelevant to the court proceedings. The UK Extradition Act (2003), passed by Tony Blair’s Labour government alongside a raft of anti-democratic “counter-terror” legislation, removed the political offences exception.

Seeking to uphold the exception, Edward Fitzgerald QC mounted a powerful case for the defence, referencing centuries of legal principle and internationally recognised standards of human rights.

The bar on extradition for political offences “is regarded throughout the world as a fundamental protection,” Fitzgerald argued. It is “contained in every one” of the US’s extradition treaties with Western democracies, including the Anglo-US treaty ratified in 2007.

Moreover, said Fitzgerald, “In case after case the courts have stressed the importance of respecting treaty obligations as a cardinal principle that guides the whole extradition process and the way the courts should approach it.”

Responding to the prosecution’s claim that this treaty has no basis in domestic law and so cannot grant Assange any rights, Fitzgerald referred to section 87 of the Extradition Act (2003). According to this section, the judge must decide whether a person’s extradition is compatible with the European Convention on Human Rights, adopted into English law through the Human Rights Act (1998). The extradition treaty “is the whole substratum” to Assange’s extradition. To ignore its exception for political offences was clearly an abuse of process and therefore constituted arbitrary detention, breaching Article 5 of the ECHR.

Fitzgerald then delivered a profound examination of the fundamental legal principles at stake. “The right to liberty is not just the right to liberty in accordance with tabulated statutory provisions, but the wider test of ‘is this non-arbitrary?’”

He continued, “due process of law is a compendious expression that invokes the concept of rule of law itself and universal standards of justice.”

Fitzgerald cited three key cases to make his point.

Firstly, R v Mullen (2000), in which abuse of process was successfully invoked because the behaviour of the British authorities in the extradition procedures involved them “acting in breach of public international law.”

Secondly, Thomas v Baptiste (2000), where the Privy Council “found that the due process clause of the Trinidad Constitution ‘invokes the concept of the rule of law itself,’” allowing defendants to appeal to a treaty unincorporated into domestic Trinidadian law. As Fitzgerald was forced to spell out in a British court in 2020, “the due process law in Magna Carta is still part of our law.”

Thirdly, Neville Lewis v Attorney General Jamaica (2001), which held that the constitutional concept of “the protection of law” trumped the Jamaican state’s reliance on the very authorities cited by the prosecution in the Assange case. The same constitutional concept is established in the Fifth Amendment to the US Constitution, which is the “cornerstone of the constitutional protections offered to its citizens.”

Fitzgerald concluded, “the prosecution’s simplistic rejection of any reliance on the requesting state’s duties under public international law… ignores the fact that the abuse of process jurisdiction is there to protect against the disregard for the rule of law, of which international law itself forms a part.”

Putting the matter more sharply, the prosecution seeks to appeal to a wholly reactionary, nationalist, black letter reading of the law—resting on the anti-democratic legislation of the Blair government.

Prosecutor James Lewis QC’s rebuttal claimed that Assange “is not entitled to derive any rights from the treaty.” Parliament had “expressly abrogated” the political offence exception with the Extradition Act (2003) and that therefore “the operation of the law has deprived Mr Assange of the challenge he wishes to make.”

Lewis admitted, “It may be slightly surprising to other foreign states but in English law the treaty is irrelevant.”

The hearing continues.

Publidshed at https://www.wsws.org/en/articles/2020/02/27/assa-f27.html