The Ethiopian capital’s tallest building is a mighty tribute in stone and wood to the new Scramble for Africa. And although Israel did not exist when Europe embarked on its New Imperialism in the late 1880s, it certainly wants to join in now.

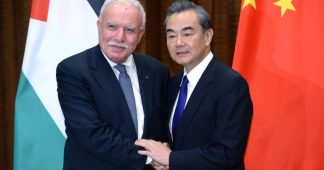

But Tel Aviv’s aim is not the same as that of, say, Beijing, which gave the nearly R3-billion tower complex in Addis Ababa to the African Union in 2012. It was opened with a symbolic giant, golden key.

Under the coalition government of Israel, headed by Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu of Likud, the country wants to secure the support of as many African countries as it can get to buy into its “innovation” trope. It does this in denial of its human rights abuses and flouting of international law in the West Bank, East Jerusalem and Gaza.

Representing 55 countries, the political capital of Africa on Addis Ababa’s Roosevelt Street is a key target of Israel’s dream on the continent. And the settler-colonialist state is hoping that dream may be realised by way of Lomé, Togo, which is hosting the first Africa-Israel summit in October.

Addis and Lomé are separated by a five-and-a-half-hour flight — a straightfoward route from east to west which Israel hopes will secure it a crucial observer seat at the AU. That seat would, in turn, allow it unprecedented access to the AU’s member states whose buy-in it needs at the United Nations to oppose resolutions critical of its occupation of Palestine.

Right now, Israel seems likely at least to get support for its AU bid from Kenya, Ethiopia, Rwanda and Uganda — the stops on Netanyahu’s four-nation visit to Africa last year. It’s been nearly three decades since an Israeli prime minister staged such a tour, although Israel also has diplomatic ties with another 41 AU member states.

South Africa may be one of those 41, but it captured the attention a fortnight ago when it announced it wouldn’t go to the Togo summit out of solidarity with Palestinians. Fellow boycotters include Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia and Mauritania, but those are outweighed by the roughly 20 countries believed to have registered delegates.

Although it is significant that the quartet of mostly Islamic nations rejected an invitation, it’s South Africa’s refusal that is a coup for the Popular Conference for Palestinians Abroad (Palesabroad) and the central committee of the Palestinian-led Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions (BDS) Movement in Ramallah.

Pretoria’s decision was announced by Sean Benfeldt, South African ambassador to Syria and Lebanon.

The Palestinian BDS national committee hailed South Africa’s decision as “an important step”. Speaking to Quds Press, committee member Nisfat al-Khafsh said this would encourage other countries and was a critical part of efforts to pressure Israel to abide by international law.

“South Africa,” said Khafsh, “is the country most committed to the calls for boycotting and divesting the Israeli occupation.”

Yet it’s not as linear as it might seem. In July, Minister of Water and Environmental Affairs Edna Molewa — who heads up the ANC’s foreign affairs portfolio — reported on the ruling party’s deliberation over a South African embassy downgrade in Israel. Disputes between factions meant no final recommendation could be released.

Palesabroad meanwhile sent a letter to every AU member on August 7 reminding African leaders that “Israel remains the only occupying power in the 21st century”, describing the “unjust and inhumane” blockade on Gaza, the confiscation of land, the continued building of illegal settlements, attacks on Palestinians, apartheid processes and the denial of the right to return. It aligned Israeli apartheid with all acts of colonialism and occupation, and said that hosting Israel on the African continent was “an outright dishonour to the sacrifice [of African people]”.

It’s tough going. The solidarity movement for Palestine sometimes feels like it is pushing mud through treacle. Especially in the international media, the support for those affected by Israel’s brazenness about its military occupation and oppression of Palestinian people waxes and wanes.

So it was with the solidarity movement to end apartheid that finally broke through in the early 1980s, albeit largely off the back of prescient Western capital, which saw opportunities glittering on mining headgear and off the glass cladding on then modest skyscrapers in Johannesburg.

Sponsored by Israel and Togo, the Africa-Israel summit is underpinned by the Israeli diplomatic service and the corporate Africa-Israel Connect, with the theme Innovation for a Shared Prosperity. “Innovation” encompasses security, technology, agriculture, health, water and energy. It’s believed trade between sub-Saharan Africa and Israel is relatively high at about R100-billion. Recent indicators show that sub-Saharan Africa exports to China — its biggest trading partner — are worth about R360-billion, to India and the United States about R140-billion, the Netherlands and South Africa about R9 100-million, with imports from China at about R566-billion, South Africa R236-billion, India R190-billion, Germany R182-billion and the US, R157-billion.

So there’s still a way to go for Netanyahu — if it’s only about trade.

Activists and those who support the liberation of Palestine, whether through a two-state or one-state solution, would say it’s not. And that’s why an organisation such as Palesabroad is agitating for “a counter-movement” in Africa that “can act in parallel” to Israel’s push to embed itself on this continent.

Netanyahu told a group of 15 African leaders at a closed-door meeting in New York last year that Africa “excites our imagination”. And indeed, there were takers for that sentiment, most vocally Togolese President Faure Gnassingbé, who was reported in The Jerusalem Post as saying that those African countries “hesitant about strengthening ties with Israel should stop looking for excuses and work with Jerusalem to safeguard Africa’s interests”.

But the focus on Israel wanting to be allowed into the AU has its own irony. That the AU’s headquarters is in Ethiopia means Israel’s possible presence in that building will denote a different role to its current diplomatic status in Addis. Thousands of Ethiopians consider themselves part of international Jewry. Only, of late, they’re struggling to be “repatriated” when others in the diaspora, particularly those born in South Africa, seem to have little to no trouble gaining entry.

This takes us back to 2011 when Ethiopian-born journalist Rachamim Elazar was named Israel’s next ambassador to his home country.

There were some in the federal democratic republic who dared him to be an African bulwark again Zionism. These were weary, if not cynical, Beta Israel — Ethiopian Jews.

More than 30 years of turmoil have passed since they were first churned into the tornado of Cold War geopolitics and then blown on to the periphery of catastrophic neocapitalism.

They’d been promised as Jewry, and Africans, that they’d be protected against further catastrophe in their home country by finding permanent shelter in Israel. Although three airlifts took place, these were not exactly mass migrations — and there was a bit of a catch with the first one, Operation Moses, in 1984.

Elazar was seen by more progressive Beta Israel as being gifted a golden chance not only to assist in “taking home” Ethiopia’s remaining Jews, but also to raise issues about what kind of country Africans in the Jewish diaspora would like to live in.

He seemingly failed to take that chance. In 2014, the Israeli government said there would be no more immigration from Ethiopia. Two years later, a very light “new wave” of immigration began — at about the time of Israel’s “breakthrough” in Africa.

Elazar was part of US-led efforts in the 1980s to “save” Beta Israel from internecine terror after the overthrow of the Addis Ababa aristocracy in the 1970s. The thing was that, even though he wasn’t a member of the Knesset, anyone who represented the State of Israel abroad may as well have been a proxy for its Zionism.

His countryman Aleli Admasu struggled more. He was the victim of that “catch” in 2008 when Likud’s election committee at first disqualified him from running on its slate, saying he was ineligible for an immigrant slot. This was because he had made aliya — the immigration of Jews from the diaspora — in 1983 and Likud had declared that 1985 was the earliest date from which a candidate could be considered a new immigrant.

This would also have affected those who arrived via Operation Moses and supported Likud. Yet politician Avraham Neguise managed to enter the Knesset on a Likud ticket, thanks to the influence he managed to wield in the party over the return of Beta Israel. This helped to patch together the precarious coalition that secured Likud the 2015 elections, but the love hasn’t lasted, leaving 9 000 Falash Mura without Jewish citizenship.

The Africa-Israel summit turns its back on those and so many other wounds. Togo, and others in attendance in October, may regret giving Israel this entry point into the new Scramble for Africa.

* Janet Smith is an independent journalist and writer