by Jan 01, 2020

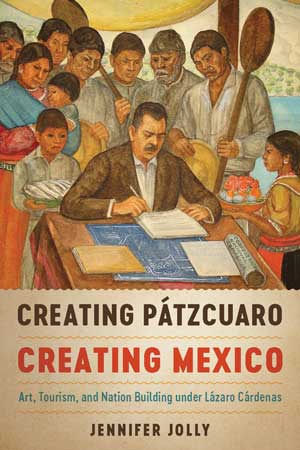

Jennifer Jolly, Creating Pátzcuaro, Creating Mexico: Art, Tourism, and Nation Building under Lázaro Cárdenas (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2018), 352 pages, $29.95, paperback.

Though perhaps not as dramatic as the story of Huitzilopochtli guiding the Mexica to the site of Tenochtitlan—upon whose ashes Mexico City presently stands—modern nation-states still appeal to myths when trying to establish a sense of shared national identity among their subjects. In the United States, many of us are taught that our identity originates in a so-called melting pot, in which different (mostly white European) ethnicities come together. In Mexico, the dominant myth has been one of mestizaje, a mixing of indigenous and Spanish culture and traditions into a uniquely Mexican identity. In both cases, the myths gloss over the genocide and territorial dispossession to which the indigenous inhabitants were subjected by European colonists, and exclude or deny the contributions of different (typically nonwhite) cultures and ethnicities. Calling attention to the way that national identities are almost by definition built around such exclusions, and continue to be weaponized in the framing of the citizen against the unwanted other, therefore remains an important task in the development of alternative subjectivities capable of challenging the authority and hegemony of the nation-state and its attempts to divide the working class.

Though perhaps not as dramatic as the story of Huitzilopochtli guiding the Mexica to the site of Tenochtitlan—upon whose ashes Mexico City presently stands—modern nation-states still appeal to myths when trying to establish a sense of shared national identity among their subjects. In the United States, many of us are taught that our identity originates in a so-called melting pot, in which different (mostly white European) ethnicities come together. In Mexico, the dominant myth has been one of mestizaje, a mixing of indigenous and Spanish culture and traditions into a uniquely Mexican identity. In both cases, the myths gloss over the genocide and territorial dispossession to which the indigenous inhabitants were subjected by European colonists, and exclude or deny the contributions of different (typically nonwhite) cultures and ethnicities. Calling attention to the way that national identities are almost by definition built around such exclusions, and continue to be weaponized in the framing of the citizen against the unwanted other, therefore remains an important task in the development of alternative subjectivities capable of challenging the authority and hegemony of the nation-state and its attempts to divide the working class.

As part of this deconstruction of national identity, Jennifer Jolly, an associate professor of art history at Ithaca College, analyzes the tourist town of Pátzcuaro in the west-central Mexican state of Michoacán as a microcosm of cultural power in which tourism, art, history, and ethnicity were woven together under the presidency of Lázaro Cárdenas del Río (1934–40). Cárdenas’s term is known as the height of Mexico’s land-reform efforts, saw the historic nationalization of the petroleum industry, PEMEX, and is still regarded by many as the most popular and progressive of Mexico’s postrevolutionary sexenios (presidential terms). Cárdenas took power over a state that had been repeatedly plagued by rebellions, assassinations, and other violence since the presidency of Álvaro Obregón Salido in 1920 signaled the official end of the revolutionary struggle that began in 1910 with Francisco Ignacio Madero González’s challenge to the thirty-one-year presidency of José de la Cruz Porfirio Díaz Mori. Cárdenas is credited by many with bringing a degree of stability to Mexico by incorporating different sectors into the state apparatus, without generally taking much of the blame for the state’s rightward shift in the decades following his tenure.

Published at https://monthlyreview.org