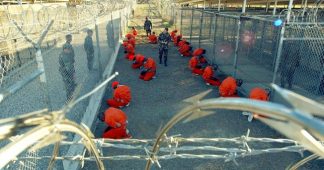

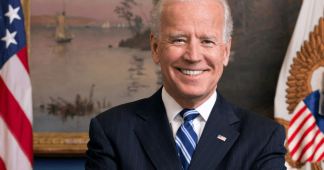

President-elect is expected to close prison camp before its 20th anniversary next year, analysts say

Sheren Khalel

13 January 2021

There are few who are expected to benefit more from US President-elect Joe Biden’s incoming administration than the 40 men languishing in the Guantanamo Bay prison camp.

Established in the aftermath of the 9/11 attacks at the US military base that has been present in southern Cuba for more than a century, activists have this week – as the prison marked its 19th anniversary – again urged authorities to close the notorious facility.

While the Obama-Biden administration (2008-2016) failed to meet its campaign promise to close the prison, it did release 197 detainees, leaving 41 others behind – most of whom have not been charged with a crime.

Now, as Biden heads to the White House with both chambers of Congress in Democratic control, hopes that the facility may finally be shuttered have been renewed.

“When President-elect Biden comes into office, his administration is going to face the choice: Do we want to hold people for life without charge in a military prison, or do we want to transfer them and close the prison?”, J Wells Dixon, a senior staff attorney at the Center for Constitutional Rights (CCR), told Middle East Eye

Closing the prison will likely take time, but for at least six men in the offshore military base, Biden’s victory is a near-guarantee of freedom.

All but one of a group of six were approved for release near the end of Obama’s second term: Sufyian Barhoumi of Algeria; Abdul Latif Nasir of Morocco; Muieen Adeen al-Sattar, a Rohingya who was born in the UAE; Ridah Bin Saleh al-Yazidi of Tunisia, and Tofiq al Bihani, a Yemeni born in Saudi Arabia. And in December, Hani Abdullah of Yemen became the only inmate to have been cleared for release under the Trump administration.

“These people [will be] the priority for the Biden administration, and for advocacy groups, simply because they’ve already been cleared,” Cole Blum, advocacy assistant at Human Rights First, told MEE.

Guantanamo’s controversial Periodic Review Board (PRB), a parole board-type panel, approved the six men to be repatriated to their homelands or transferred to third countries, but US President Donald Trump shut down the State Department office that negotiated prisoner transfers before it could do so.

The outgoing president has been very much against releasing inmates from the facility – saying he actually wanted more people sent to the prison camp.

“We’re gonna load it up with some bad dudes,” Trump said at a 2016 rally, referring to Guantanamo Bay. “Believe me, we’re gonna load it up.”

While Trump did not end up sending new prisoners to the facility, during his four years in office only one inmate was released – Ahmed Muhammed Haza al-Darbi, a citizen of Saudi Arabia – a country the president had embraced as a top ally.

Question of guilt

The process of being approved by the review board is complicated and currently requires an inmate to be cleared by six federal agencies: the departments of State, Defense, Justice and Homeland Security, as well as the Office of the Director of National Intelligence (ODNI) and the Joint Chiefs of Staff.

The involvement of the ODNI, which includes the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), has been controversial, as the agency oversaw the alleged torture of many of those held at Gitmo.

To rule for release, all six department representatives, whose names are classified, must agree unanimously.

Advocates and rights groups have called for the PRB to be reformed under the Biden administration in order to make the process swifter and fairer.

Mohamedou Slahi, a former Guantanamo inmate who was released by the PRB in 2016, 14 years after his capture, has called on the US to address a major issue in the release process – the assumption of guilt.

During a webinar on Monday that focused on the need to close Guantanamo Bay, Slahi, who has written a book about his detention and torture and recently helped in the making of a movie on the topic, said the US needed to state implicitly that those transferred out of the prison by the review board had done nothing wrong.

“When the most powerful country in the world suspects you of something, you are guilty,” Slahi said.

During the event, he said he had been treated like a criminal since his release and has had great difficulties obtaining visas – even after finally being granted a passport, despite never having been charged or found guilty of a single crime.

Reforming the review board

Blum, whose organisation advocates for Guantanamo detainees and acts as an independent legal observer in its court procedures, also said the Biden administration needed to make some major reforms in the review board process.

Currently, the PRB does not address the legality of an inmate’s detention in Guantanamo or the guilt or innocence of any prisoner. It only addresses whether the person should be deemed a threat to US national security

“We need [the review board] to take into consideration factors like the considerable passage of time since they were captured, and not treat previous denials of allegations as evidence of them trying to hide anything, or them admitting guilt previously, and they need to screen out information that was obtained from torture or other cruel punishment they’ve been through,” Blum said.

“I think that the priority would be to do a new round of hearings for all detainees, but the new round of hearings should include those reforms,” he continued, stressing that most of the men still in the prison camp have already been tortured by the US and held in custody for almost two decades, regardless of legal status.

After the release of the six that have already been approved by the review board, 25 others qualify for a possible PRB release, as no charges have been levied against them.

The two men who have been convicted and the seven who are currently charged with war crimes cannot be processed through the board – which brings up another obstacle that the Biden administration will face if it tries to close the prison camp: its war court.

Closing Guantanamo

Past attempts to close Guantanamo Bay prison were met with resistance, largely because of the political cost coming from constituents still reeling from the 9/11 attacks, in which almost 3,000 people were killed.

After two decades, $6bn in taxpayer funds, countless scandals, detailed revelations of torture and a failure by the war court to properly prosecute those on trial, advocates say the political will may now exist to finally shutter the facility.

“I do think closing Guantanamo, and in particular, transferring the cleared men is going to be a priority for Biden. And the reason I say that is because it certainly seems to me that there is broad interest in turning the page on the post-9/11-era and moving the country forward,” said Wells Dixon, the CCR attorney.

“I think if we learned anything from the Obama administration, it is that you can’t move forward without dealing with the past. And that includes Guantanamo,” he said.

CCR, a 55-year-old non-profit legal advocacy organisation, released a detailed report last year breaking down the steps necessary to close the entirety of the prison camp, including its floundering war court.

The Biden administration would first need to appoint senior officials to oversee efforts to close the facility, re-open the shuttered State Department office that negotiates repatriations and release those already approved for transfer, CCR said in its report.

Next, it would need to resolve the status of the men who have been neither charged nor cleared.

“At this point, if they’re not already charged, they’re not going to be tried. So really, what we’re talking about is release,” Wells Dixon said.

After dealing with the men who have not been charged, the administration would need to go to work on closing down the prison’s war court – the Office of Military Commissions (OMC) – and instead seek to hold trials in US federal court.

‘Holding our breath’

In the 14 years since the war court’s establishment, only two of the original 779 people that the government has acknowledged were held at the prison camp have been convicted of crimes.

“It is, and has been for many years, an open secret in Washington, DC, and the broader United States that the military commissions have failed – they certainly have failed to achieve any measure of justice for the victims of 9/11,” Wells Dixon said.

The most controversial of the cases, dubbed “the 9/11 case”, in which five men are being prosecuted for alleged direct involvement in the attacks, has been ongoing for a decade but has not even entered the actual trial portion of the legal proceedings.

“I think that it is absolutely inevitable that the Biden administration is going to have to figure out what to do with the very small number of men who are charged by the military commission,” Wells Dixon said.

“I say it’s inevitable because we are rapidly approaching the 20th anniversary of the 9/11 attacks, and when we reach that anniversary – if not before – there will be a lot of public attention on what has happened over the last 20 years, and specifically, what is going on with respect to the five men who are alleged to be responsible for those attacks,” he continued.

Most legal experts that argue for the men to be tried within the US Federal Court system say that in order to do so, provisions within the 2009 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) that prohibit the transfer of Guantanamo detainees to the US for prosecution, incarceration, and medical treatment would need to be repealed by Congress.

Others have argued that detainees could still go through a federal trial while being barred from stepping foot in the US – by holding virtual proceedings.

The question now is whether the Biden administration will “revert reflexively to the thinking of the Obama administration” and leave these sort of decisions to Congress, or if the new president will take executive action, Wells Dixon said.

“There are a number of legally viable options available to the Biden administration under current law, just as there were to Obama, the question is whether the administration will take advantage of those opportunities,” he said.

“We are holding our breath to see how the Biden administration will approach the issue of Guantanamo… the stakes are high, because we’re talking about lifetime detention without charge.”

Published at www.middleeasteye.net