22 June 2020

In recent weeks, participants in demonstrations against police violence in the United States have demanded the removal of monuments to Confederate leaders who waged an insurrection to defend slavery during the American Civil War of 1861-1865.

But the justifiable demand for the removal of monuments to these defenders of racial inequality has been unfairly accompanied by attacks against memorials to those who led the Civil War that ended slavery and the American Revolution, which, in upholding the principle of equality, for the first time placed a question mark on the institution of slavery.

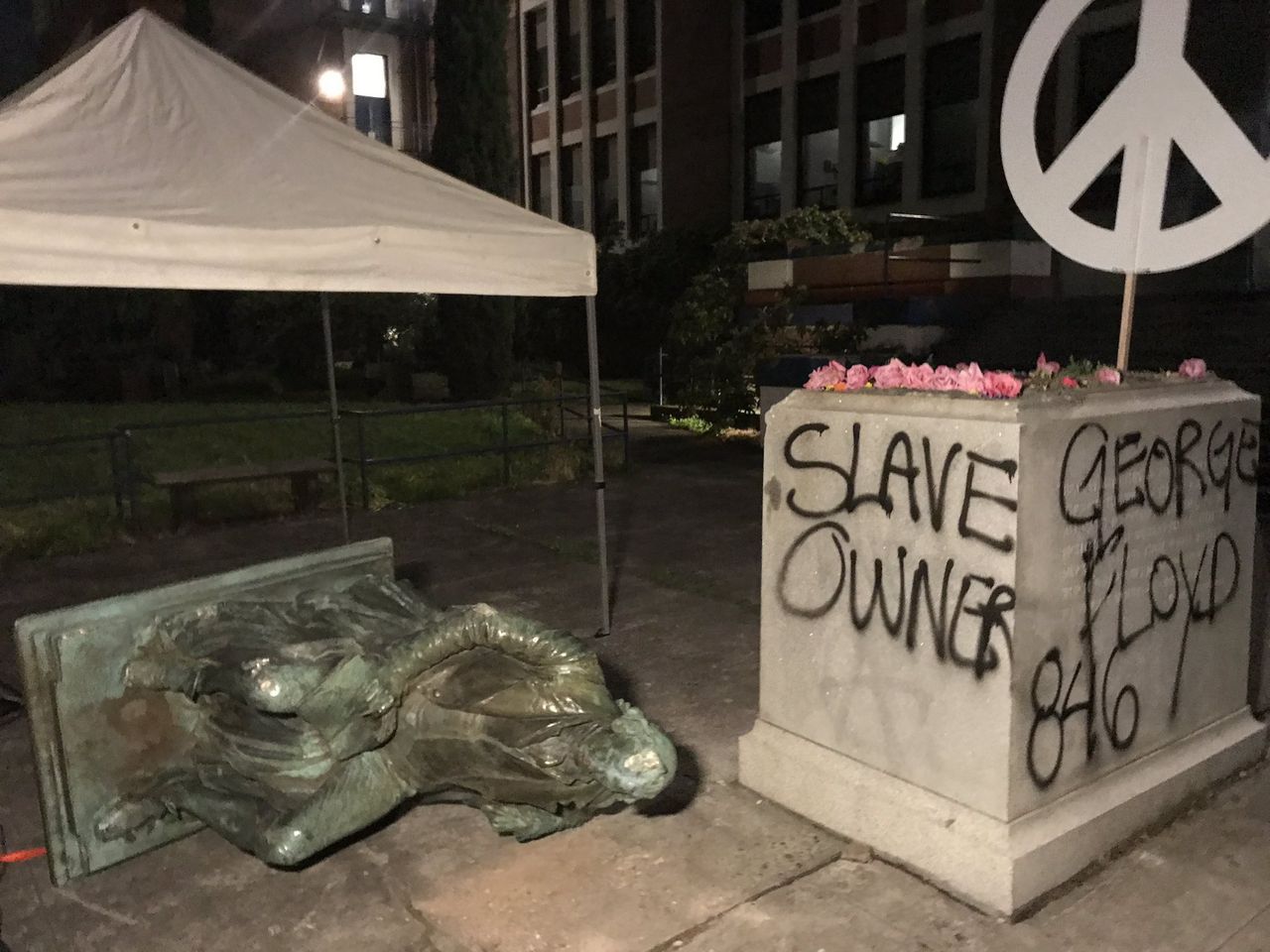

Last Sunday, a statue of Thomas Jefferson, the author of the Declaration of Independence, was torn down in Portland, Oregon, followed four days later by a statue to George Washington, who led the forces which defeated the British during the American Revolution.

On Friday, protesters in San Francisco knocked over a statue of Ulysses S. Grant, who commanded the Union to victory in the Civil War and suppressed the Ku Klux Klan during Reconstruction.

Now a social media campaign has been launched to see the removal of the famous Emancipation Memorial statue in Washington, D.C., which depicts Abraham Lincoln standing above a kneeling slave who has been freed. The statue, erected in 1876, was in fact paid for by freed slaves. Frederick Douglass gave the oration at its dedication.

No one can object to the removal of monuments to the leaders of the Confederacy, who dedicated their lives to the rejection of the thesis that “all men are created equal.” These figures sought to “wring their bread from the sweat of other men’s faces,” in the words of Lincoln’s second inaugural address.

The monuments to the leaders of the seceded states were erected in a period of political reaction following the end of Reconstruction, with the aim of legitimizing the Confederacy as part of the “lost cause” school of historiography, which denied the revolutionary character of the American Civil War.

But the removal of monuments to the leaders of America’s revolutionary and civil wars has no justification. These men led great social struggles against the very forces of reaction that justified racial oppression as an incarnation of the fundamental inequality of human beings.

It is entirely possible that those who participated in the desecration of monuments to the leaders of the two American revolutions were not conscious of what they were doing. If that is the case, then the blame must be placed on those who incited these actions.

In the months preceding these events, the New York Times, speaking for dominant sections of the Democratic political establishment, launched an effort to discredit both the American Revolution and the Civil War.

In the New York Times’ 1619 Project, the American Revolution was presented as a war to defend slavery, and Abraham Lincoln was cast as a garden variety racist.

Historical clarification of some of the major historical figures involved is necessary.

Thomas Jefferson was the author of what is arguably the most famous revolutionary sentence in world history: “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal.” That declaration has been inscribed on the banner of every fight for equality ever since 1776. When Jefferson formulated it, he was crystalizing a new way of thinking based on the principle of natural human equality. The rest of the preamble to the Declaration of Independence spells out in searing language the natural right of people to revolution.

The American Revolution delivered a powerful impulse in that direction that led to the French Revolution of 1789 and the greatest slave revolt in history, the Haitian Revolution of 1791, in which slaves liberated themselves and threw off French colonial domination.

George Washington was the commander of the Continental Army in the American Revolution (1775-1783), in which the 13 colonies asserted their independence from their British colonial masters. Washington, in a decision that electrified the world, left behind his military post and returned to private life, helping to institute in practice the separation of the civilian from military power in the republic.

Abraham Lincoln must rank as one of the greatest figures of modern history. The leader of the North, or the Union, in the Civil War, his historical purpose was revealed over the course of that war to be the destruction of what contemporaries called “the Slave Power.” Lincoln saw that struggle through to a victory in April of 1865, only days before he was martyred to the cause of human liberty. The world grieved at his death. This was so in both the North and South, and especially among the freed slaves. “The world only discovered him a hero after he had fallen a martyr,” Marx wrote.

Ulysses S. Grant was a hero of the Civil War whose stature was second only to that of Lincoln. Prior to his ascension to lead the entire military effort in 1864, the cause of the Union was hampered by generals who opposed the emancipatory impulse of the Civil War.

Grant and his trusted friend General William Tecumseh Sherman recognized that to defeat the South required a war for the destruction of slavery, root and branch. “I can’t spare this man. He fights,” Lincoln said of Grant. In the White House, Grant was overwhelmed by the force of capitalism unleashed by the Civil War, but he defended the freed slaves and suppressed the Ku Klux Klan. After he retired from the presidency in 1877, Grant toured Europe where throngs of workers attended his public events and speeches.

The attacks on the monuments to these men were pioneered by the increasingly frenzied attempt by the Democratic Party and the New York Times to racialize American history, to create a narrative in which the history of mankind is reduced to the history of racial struggle. This campaign has produced a pollution of democratic consciousness, which meshes entirely with the reactionary political interests driving it.

It is worth noting that the one institution seemingly immune from this purge is the Democratic Party, which served as the political wing of the Confederacy and, subsequently, the KKK.

This filthy historical legacy is matched only by the Democratic Party’s contemporary record in supporting wars that, as a matter of fact, primarily targeted nonwhites. Democrats supported the invasion of Iraq and Afghanistan and under Obama destroyed Libya and Syria. The New York Times was a leading champion and propagandist for all of these wars.

The New York Times and the Democratic Party seek to confuse and disorient the democratic sentiments of masses of people entering into political struggle against the capitalist system and its repressive forces within the state because they know that the growing multiracial, multinational and multiethnic movement of the working class will take place in direct opposition to their own politics.

There are many people involved in the taking down of these statues who do not understand the political implications of what they are doing. However, ignorance is not an excuse. Actions have an objective significance. Those who attack the American Revolution help contemporary reaction.

Tom Mackaman and Niles Niemuth