Exclusive: The European Union’s neoliberal economic orthodoxy has spread income inequality and even poverty across the Continent, spurring extremist movements to challenge this system, reports Andrew Spannaus.

By Andrew Spannaus

The rise of protest movements across Europe, with increasing support for extremist candidates and political parties, comes against the backdrop of a growing sense of insecurity for the middle and lower classes across the continent.

Less stable employment conditions and the stagnation or regression of salaries have created the fertile ground for populist movements on the right in particular, which now mix their traditional nationalist and anti-immigrant rhetoric, with criticism of the economic orthodoxy of the supranational European Union (E.U.) institutions.

In recent years the prevailing response from economists has been that many Western nations are simply unable to compete in sectors dominated by low costs and the high efficiency unleashed by globalization. This narrative, however, is used to hide a more troubling reality: government institutions have contributed directly to the economic difficulties with their own actions, driving down living standards through multiple waves of austerity and blocking attempts to break from the neoliberal principles that dominate among E.U. institutions.

The latest Economic Bulletin from the European Central Bank (ECB) presents a range of statistics that highlight the worsening of living conditions even among the wealthiest countries on the continent. First of all, the ECB admits that the official unemployment rate, high but improving, fails to account for categories such as workers who are part-time for economic reasons or who are no longer actively searching for a job. As we have known in the U.S. for years, broader measures of unemployment can make the actual rate practically double, taking into account problems that the headline statistic easily masks.

According to Prometeia, a respected Italian economic research institute, this alternative view of the weakness of the labor market may explain “why poverty levels are not following a descending path, since official labor market statistics may have hidden underemployment.”

The growth in the poverty rate across Europe confirms this impression, and shows that the vaunted social welfare state that European countries are known for has failed to protect citizens from the effects of the economic crisis.

In aggregate terms, for the entire Eurozone (the 19 countries using the common currency), poverty increased from 16.1 percent of the population in 2007, to 17.2 percent in 2015. This includes rises in wealthy countries, such as Italy, France, the Netherlands and Germany. The biggest surprise is found in the figures for Germany: poverty jumped by 1.5 percent over the cited time period, three times the increase in Italy and France.

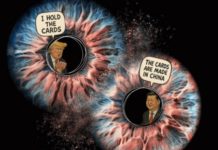

Although it may not seem like a large rise, this statistic is notable because it goes against the common narrative of the strength of Germany as the leading economy in Europe. Germany has a large budget surplus (currently around 8 percent) and is a major player in industrial exports, in particular to new markets in Asia.

Based on this strength, German politicians often take a hard line on budget restrictions at the E.U. level, demanding that countries with greater difficulties cut spending and avoid violating the monetary parameters established for the Eurozone, which prohibit running deficits in order to boost public investment. “If only they were virtuous like us,” the attitude is, “then they also would see economic growth and more social cohesion.”

Expanding the ‘Working Poor’

The statistics on poverty undercut this argument. Germany’s economy has certainly continued to expand, but one of the side-effects has been the impoverishment of large segments of the population. If we go further into the numbers, we find that Germany has seen a big jump in working poor over the past 10 years. From a level below 5 percent in 2007, the figure reached 10 percent in 2014, before leveling off.

Clearly, one of the competitive advantages of the German economy has been blocking wage growth, and even reducing salaries and social protections for much of the population. Whereas in some other countries the gains from increased productivity have been shared with workers, in Germany the benefits have gone mostly to the top.

The main factor in creating this situation was the series of labor market reforms conceived in the early 2000s under the Hartz Commission. Peter Hartz, the Personnel Director of Volkswagen, was called on by then-Chancellor Gerhard Schroeder to come up with a plan to address the high unemployment rate. The resulting proposals concentrated on increasing flexibility in the labor market, in particular changing the structure of subsidies for unemployment and welfare services.

The most severe measures came under “Hartz IV,” implemented in 2005, which forces those who are out of work to accept any offers they receive from the Federal Employment Office, on penalty of losing the meager benefits they already receive. This work requirement means that qualified professionals can find themselves earning 1 or 2 Euros an hour in “mini-jobs,” reduced to menial labor in arguably the most advanced country in Europe.

The social and political effects of the Hartz reforms are evident. Approximately 6 million people are in the subsidy system, and entire areas have come to be known as “Hartz IV neighborhoods,” dominated by people who feel trapped by a system that has provided flexibility for employers, but caused accelerating economic inequality.

Not surprisingly, it is in these areas that populist movements such as Alternative for Germany (AfD), or parties at the left or right extreme of the political spectrum, get their highest vote totals.

‘Success’ at a Cost

From a certain standpoint, Germany’s success in improving its economic indicators through the impoverishment of part of its population actually appears preferable to other alternatives under current E.U. economic policy.

Given the strict budget rules prohibiting large-scale public investment, it has become mandatory to enact “structural reforms” aimed at achieving labor market flexibility, and allowing the entry of private capital into markets previously restricted by public regulations. Germany acted in advance, and also gave a massive public bailout to its banks; now it is held up as an example for others.

A worse scenario has played out in other European countries since 2010: not only structural reforms based on neoliberal ideology, but massive levels of austerity that “cut out the middle man,” so to speak, directly reducing living standards through tax hikes and deep cuts in social services.

When the real estate bubble burst in Spain starting in 2008-2009, for example, the country was forced to implement harsh budget cuts, raise the retirement age, and cut social services. Unemployment rose to almost 25 percent, with youth unemployment close to 50 percent, while the banks were bailed out under an agreement with the E.U., the IMF and the ECB (known as the “Troika”). After years of austerity the economy is now growing again; in this case as well, the cost has been the impoverishment of large swaths of the population.

In Greece, the situation is even more dramatic. Under fire for presenting misleading or false budget numbers – with the help of international banks such as Goldman Sachs – and criticized for widespread tax evasion and an overly generous social state, the Greek people have been subjected to continuous austerity. As a result approximately 15 percent of the population now lives in extreme poverty; a classic case of the cure being worse than the disease.

The E.U. and the IMF have cheered Greece’s commitment to fiscal responsibility, while being forced to admit that this “progress” has “taken a heavy toll on the society and tested its endurance.” (IMF report, Feb. 7, 2017).

One might think that these three examples of increased poverty in countries with very different images both inside and outside of Europe would lead to a profound reappraisal of the austerity policies implemented in recent years. For now, however, the leading players in the E.U. institutions have shown no intention to make a fundamental change; the “reforms” must go on.

* Andrew Spannaus is a freelance journalist and strategic analyst based in Milan, Italy. He is the founder of Transatlantico.info, that provides news, analysis and consulting to Italian institutions and businesses. His book on the U.S. elections Perchè vince Trump (Why Trump is Winning) was published in June 2016.