All the glisters is not gold;

Often have ye heard that told;

Many a man his life hath sold,

But my outside to behold;

Gilded tombs do worms enfold.

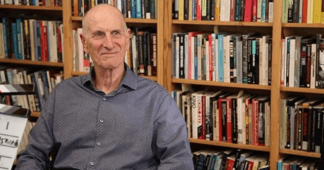

By Professor William Mallinson(*)

Introduction

Do you care for Greece? A country that does not educate its inhabitants properly runs the danger of not being a solid country, and being exploited by all manner of selfish foreign interests. Greek school-leavers unable to enter free state universities either study abroad, or turn to Greek private colleges offering franchised foreign degrees, which they then try to have recognised by the Independent Department for the Implementation of European Legislation (ATEEN). The Greek recognition body, the National Academic Recognition and Information Center (DOATAP) is only responsible for degrees earned after studies abroad at foreign universities. This can confuse some people. If you are seriously concerned, then read on, and I shall try to show you the wood and the trees. Unfortunately, in private higher education, there are some owners whose sole purpose is profit, which comes from student financial fodder. This article is written in the public interest, and more specifically, the interest of parents and students. For anyone who thinks that I am being hard, remember that the only way to improve is to identify failings through criticism, in order to get rid of them. Sometimes, it is therefore necessary to rock the boat of apathy.

The American Connexion

Despite disappearing for a while, the American ‘University’ of Athens seems to have returned, or has re-opened. According to a legal document, the Education Ministry withdrew recognition, and fined the establishment for using its title misleadingly.[1] Students were left in the lurch.

They had paid thousands, some studying architecture for four years, all for nothing. But this ‘university’ now seems to be back in town, trying to recruit students and, therefore, their or their parents’ money. Other American ‘universities’ have foundered in Greece: the University of Indianapolis (next to The American College of Greece’s Plaka office and ‘research foundation’), was one. Apart from its Athens ‘campus’, it had another in Tripolis, which was actually the Dean’s house. Male students were able to have their military service deferred by presenting the Defence Ministry with an official translation implying that they were studying in America. And even the then American US ambassador, Miller’s, wife taught there. While on the subject, the American College of Greece (Deree) cannot escape scrutiny: most of their degrees are from the British Open University, nevertheless thankfully recognised in Greece by ATEEN. But it has been known to cram semester courses into one month, which hardly gives students the space to think, let alone reflect. Although they need the British Open University, their publicity states: ‘Located in Athens, ACG is an independent, not-for-profit, nonsectarian, co-educational institution that offers the best of the American learning experience in the cradle of Western civilization, a city that is alive with history, passion and creativity.’

A particularly shocking case of an American college was that of La Verne University, which closed down suddenly in 2004, without prior notice to staff or students. One professor left in financial ruin died of a heart attack, leaving behind a wife and child.

The Italian and British Connexion

There is another– but distance-learning – university, recognised by the Italian Ministry of Education.

It claims to have closed down its offices in Athens recently, citing problems with DOATAP, leaving many students wondering. An email from of 7 December 2021 states: ‘The Board of Directors has decided to stop the presence of the University in Greece. In this respect, the rental contract for our office in Athens has been terminated. The reasons behind that decision are several and include, inter alia, the problems which still exist with DOATAP in the recognition process of our programs.’ Apparently, current and new recruits will now take their examinations on line, although a hotel has also been mentioned, with all the associated difficulties in avoiding cheating. Yet according to their partner in Greece, they are still taking on students.

DOATAP is not the competent authority for the recognition of degrees that have been awarded to students of the American University of Athens or of any other private establishment in Greece. This responsibility falls to ATEEN. As part of recent changes, there was media speculation that ATEEN would join the DOATAP. But according to Greek legislation, the bodies remain separate. Since ATEEN is responsible for professional recognition, some students of Unimarconi circumvent DOATAP by applying to ATEEN for recognition. But it is not always easy to draw the line between what is strictly academic and what is purely professional.

Despite their apparently closing down, the university has hired lawyers to deal with DOATAP, which clearly has problems with recognising some of the degrees offered. Students must feel rather flummoxed. To compound the confusion, a Greek law of 21 July 2022 means that the process of recognising degrees should be simplified, based on a list of recognised foreign universities. Although this is intended to simplify, things are rarely that simple. How, for example, can a British degree in civil engineering be recognised, if the degree does not include seismology, as it must in Greece? And how are Greek students learning on line examined in Greece? Should an Italian Magistrale (which takes two years) be equivalent to a one-year Masters offered in Greece? How can it be, if the Italian Ministry of Education itself insists on two years? DOATAP can nevertheless recognise a one year Masters, provided that they are recognised as Masters degrees in the mother country.

The Italian university’s Greek partner recently emailed the following, on 29 January 2023: ‘As I understand it, the only way to protect the students is find ways to resolve any issues that they might have with DOATAP. All the information up to now indicates explicitly that in all cases DOATAP acted in bad faith and abused its power.’ Thus we can say that there is no love lost between the university and DOATAP.

On its website, the university’s Greek partner writes that on 5 May 2010, DOATAP recognised the university in Italy. This is true. What is not true is the possible implication that all its degrees are automatically recognised. DOATAP has its own ways of scrutinising, for example by thoroughly checking the credentials of awarding institutions and their degrees.

The university has a strange way of hiring some of its professors, on annual contracts, confusing into the bargain. For example, one professor signed with the TERTIUM Foundation, then with FORCOM and then with a consulting firm, Francesco Fellace. The same professor in Greece reported serious cheating at written examinations, but the university never confirmed to him whether he had failed the examination, nor to his suggestions to improve the quality of their English language written examination questions. Suggestions to improve examination regulations also went unanswered. It might seem to some that the standards adhered to in Italy are not the same as those in Greece. The university even sent a Greek professor seven thick books on psychology, appointing him to supervise theses. Yet the professor had no qualification in psychology. This is known as cutting corners, at the very least. More bizarrely, the following message recently appeared on ‘the Uiversity’s Facebook group: ‘Don’t have time and need help with your thesis? You’ve come to the right place…we also print your thesis and send it directly to your home … info whapp 33******78.’ Since I began this article, the entry has now disappeared. But there are plenty more entries offering help with, for example, theses in jurisprudence.

If any of you readers are now slightly confused, then I sympathise with you, and especially with the students. But to better understand the background, we need a spot of history.

History

For those interested in history and detective work, we should look at the past, when the future founder/owner of the Italian university, at the time a professor at La Sapienza University in Rome, came to Bournemouth as part of an ERASMUS-sponsored project to set up a European MA in Public Relations, involving several universities. This project foundered in a scandal, when which saw the head of department of Advertising and Communication at Bournemouth, Professor Wheeler, suddenly resigning: an ERASMUS official wrote to the Vice Chancellor of Bournemouth University in 1992: ‘in certain identifiable respects his reporting was not only incorrect but probably deliberately so’. Wheeler had used public money to take colleagues on holiday to Rome, rather than teach, as they were meant to. The Italian professor was incensed at his claim that teaching could not take place because of a ‘student strike’. Wheeler then moved suddenly to the Southampton Institute, where another financial farrago took place, after which he ended up at Chester, retiring recently as Vice-Chancellor, but being kept on to review international partnerships. The connexion with the Italian University is that Chester University was until recently a member of FORCOM, founded by owner of the Italian University in 1990.

At the time of the much publicised scandal at Bournemouth (the Vice-Chancellor also resigned later), the owner of the Italian university criticised Bournemouth, issuing a statement for the media, expressing indignation.

The fact that FORCOM, originally used by the Italian Professor to participate in the finally abortive European Masters, has recently been collaborating with Chester University, is therefore bizarre. Some might describe it as an unholy alliance.

China takes a more realistic view of the whole charade, and recently reversed its temporary rules in place for over two years during the COVID-19 pandemic allowing online courses from foreign universities to be delivered to students within China. The temporary rules had been justified in China as a crackdown on substandard online degree courses. China will no longer recognise online degrees from overseas establishments, if the student is studying for them in China. Greece has also reversed the COVID rules, but the EU (Greece included!) continues to recognise on line distance-learning degrees, if they are recognised by the authorities in their countries of origin.

This is of course tricky: even though the Italian University has closed down its office in Greece, Greek students are still being courted and taken on, presumably working like any Italian student, but in English or Greek, (there have been comments from students about the way the Italian on line teachers pronounce English). The serious problem comes with the examinations, particularly on line ones, and how DOATAP can be sure that they are conducted properly. DOATAP has no policing powers.

Why is Greek private higher education lacking in clarity and consistency, with a fair number of students being disappointed? The above gives some of the picture, but there is more. To its credit, the beleaguered Education Ministry managed to insist that teaching staff at private colleges need to have their own degrees recognised by DOATAP. DOATAP decides which foreign degrees to recognise. A Greek law was recently introduced to comply with Brussels rules (the so-called ‘Bologna Process’). Since 21 July 2022, this means that the degrees of Greek or foreign students from universities included in the National Registry of Foreign Recognised Higher Education Institutes will be recognised automatically for continuing studies; in other words, they will not be evaluated by the DOATAP, but by the Greek university, which will refer to DOATAP’s registers of institutions and titles, if they seek to continue their studies in a postgraduate or doctoral programme at a Greek university.

The Bologna Process is also meant to implement a system of quality assurance, to ‘strengthen the quality and relevance of learning and teaching’. In fact it is a dumbing down one-size-fits-all process. There appears to be no stipulated and organised quality assurance system. DOATAP has no policing power over the quality of teaching, and cheating. But for a degree to be recognised, there are checks on the quality controls of the degree-awarding countries. Although Greece has neither signed nor ratified the Lisbon Convention, in practice it follows the Bologna rules. The explanation for not signing is simple: Article 16 of the Greek constitution guarantees free higher education and therefore, quite logically and rightly, forbids private universities. Hence the absurd exploitation of the system by money-grubbers. In this sense, it can be argued that Greece is the last of the Mohicans in trying to maintain transparent and verifiable standards, thanks to DOATAP. In Greece, the Church, Merchant Navy and state education still work in a reasonably organised way.

When did it all begin?

American-influenced higher education began to poison Britain in the late Seventies, with profit-oriented ‘Thatcherisation’. In the late eighties, there was only a handful of universities in Britain. Then, for political reasons, the government decided to rapidly expand the number of students, a ‘clever’ way of keeping young people off the dole queue. A large number of institutions offering non-academic courses and vocational qualifications suddenly found themselves being able to call themselves universities, provided that they met certain – rather flexible (!) – criteria. New ‘degree level’ courses were hurriedly packaged, and within a few years there were suddenly over one hundred ‘universities’. In many cases it was like putting a Mercedes or Rolls Royce label on a Fiat 500 or a Mini. In the rapid expansion effort, standards fell dramatically, the teacher-student ratio deteriorated and, worryingly, entry requirements plummeted, except, of course, at the handful of traditional universities, which remain more accountable to the public (many with the Monarch as the final arbiter) than the new universities, which are run more like businesses.

To save money, the government gave these universities a large measure of financial independence, resulting in a manic quest to place a commercial market value on education, (charging students thousands of pounds), to impose alien and inappropriate ‘management’ methods, to concoct grand-sounding but empty ‘mission statements’, and to call students ‘clients’ and ‘customers’. Academically respectable B.A. and M.A. labels were slapped hurriedly onto all manner of business courses, to attract droves of gullible students. State education in Britain is now a business, with students paying huge fees. Hopefully, Greece will continue to have free state education, but should article 16 of the Constitution be abolished, there could well be a free-for-all, with calls to charge students to study at state universities as well. After all, if it happened in England, then why not Greece, which has always had a propensity to ape foreign fashions.

Greece is in danger of becoming the naïve victim of the more cut-throat of these universities, where profit is the sole motive. Many of these universities are helped by unscrupulous Greek business people, who charge students high fees to award them a degree which, in the end, is unlikely to be as good as a degree earned at a reputable university abroad, whatever the brochures claim.

Yet it is also important to point out that one reason for the proliferation of Micky Mouse degrees is the inadequacy of parts of Greek state higher education. Mediocracy sometimes reigns: a head of an academic department at a state university ran screaming from a faculty meeting, slipping up just before he reached the door, pushing it open, and scrabbling out on all fours, on two occasions. Apart from that, the same man threw a pen at a rival, hitting him just above the left eye. And he even tried to attack a young female member of staff, who collapsed and had to be taken to hospital.

The perpetrator of the screaming had also lied to the department about a serious academic matter (he hired someone unqualified for the job), in order to keep out someone whom he thought was the friend of someone he disliked (even though the latter had already left the university in question). It was very much a question of nepotism, cabalism and bullying. Unfortunately, Greek academic life is riddled with all manner of mediocracy, lying and cheating, which goes some way towards explaining why its universities rank low on the world scale. At one university in Corfu, a professor has been paid for many years, although he is too ill to teach. His teaching is covered by colleagues. Yet under Greek law, the Greek health service should care for him, and his job advertised.

Meritocracy is frowned upon. At one university, a member of faculty complained about malfeasance, was ganged up on, went into his office, and had a fatal heart attack. Most academics have to follow the line of the factions they belong to, for fear that they will not be promoted. This does of course also happen in other countries, but not to quite such an extent or so dramatically. In Greece, meritocracy has been undermined by exaggerated clientelism. This is not to say that there are not some very good universities and courses in Greece. Athens and Thessaloniki, in particular, are, generally; and in the private sector, New York College has some effective teaching. But there is room for improvement, especially in the cumbersome hiring and promotion procedures, which have driven some of the best Greek academics abroad.

We must stop Greece from being a cheater’s Paradise. Quality assurance should be the name of the game, but that seems to be under threat. If DOATAP and ATEEN continue to be entirely separate, this will be exploited by the unscrupulous money-grubbers in Greece and abroad, while standards continue to plummet. DOATAP, with its conscientious staff, needs to be given serious power and extra resources to ensure quality, whatever the protests of the unelected Eurocrats, with their attempts to homogenise what remains of decent standards. DOATAP and ATEEN should be under one organisational umbrella, to avoid inefficient overlapping. In this connexion, the distinction between the terms ‘academic’ and ‘professional’ can be confusing, given that the word ‘academic’ adds respectability to what are in essence simple training courses.

A surfeit of privatisation can lead to catastrophe: it can be argued that the recent train crash was the logical result of a dubious and greedy Italian company, subsidised by the Greek state (!), buying the Greek railway system, to the applause of the Troika. Let us hope that this does not happen to Greek education. It was, after all, Greeks who invented universities, a country’s best defence.

| (*) William Mallinson, a former British diplomat, is a historian of Anglo-Greek relations, and author of Guicciardini, Geopolitics and Geohistory: Understanding Inter-state Relations. (Palgrave Macmillan/Springer Nature), 2021). The above article was first published in Greek and is translated here from the Greek text https://www.zougla.gr/apopseis/article/i-analosimi-elines-fitites-ke-i-anagnorisi-akadimaikon-titlon-mia-paraplanitiki-istoria, https://infognomonpolitics.gr/2023/04/oi-analosimoi-ellines-foitites-kai-i-anagnorisi-akadimaikon-titlon-mia-paraplanitiki-istoria/, |

We remind our readers that publication of articles on our site does not mean that we agree with what is written. Our policy is to publish anything which we consider of interest, so as to assist our readers in forming their opinions. Sometimes we even publish articles with which we totally disagree, since we believe it is important for our readers to be informed on as wide a spectrum of views as possible.