BY ROBERT R. FARRELL AND SAMUEL C. BAXTER

The country’s resurgent pride is a relief for some and worrisome for others. Will Germany ever overcome the stigma of its past?

As Germany marched into the semifinals at the 2010 World Cup, the country’s colors—black, gold and red—flooded the stadium. Pride filled the air, radiating from the faces of joyful fans singing the Deutschland national anthem.

Such a display of German patriotism would have been uncommon just a few decades ago, a time when flag-waving and chanting would have been viewed as potential birth pangs of war.

After decades of feeling ashamed of the past, Germans are slowly beginning to take pride in their history and long list of achievements. Its authors are celebrated, German songs are gaining popularity on the airwaves—and its economy is thriving as other nations struggle. An assertive and confident Germany is boldly speaking on the world stage—and others are looking to it for support.

Younger generations, having never experienced the country’s more severe side, are optimistic about the future, adamant that their newfound sense of self-worth could never spark aggressive patriotism.

The Holocaust was generations ago, they think. This is the new Germany. One that is stable, giving, hardworking. One on which the world can rely.

Yet as national pride surges, some Germans are apprehensive about where this mindset will lead. After all, with its history mired in conflict, some fear a revival of the aggressive characteristics that have repeatedly led it into wars—often with devastating consequences—will quietly re-emerge and take its citizens by surprise.

Will Germany ever be able to escape its past?

Unexpected Position

In 2009, during the 60th anniversary of the founding of the Federal Republic of Germany, which formed after World War II, thousands flocked to the Brandenburg Gate, waving flags in support of their homeland. Patriotism resurged later that year at the 20th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall, and again in 2010 when Germany became one of the final four teams in the South Africa World Cup.

These nationalistic expressions demonstrate that the guilt associated with the country’s checkered past continues to dissipate and a sense of unity is emerging in its place. Germans once again take pride in their country and its successes: Germany is the fifth largest economy in the world by GDP and the largest in Europe. The world’s second-largest exporter, the country generates an annual trade surplus of $200 billion. Its brands—Mercedes Benz, Volkswagen, Porsche, BMW, Puma, Bayer, T-Mobile, DHL—span the world. “Made in Germany” is widely seen as a mark of excellence.

The country’s financial prudence has positioned it as Europe’s problem-solver. When the continent became economically ill, it was Germany that supported the trillion-dollar bailout package—taking responsibility for $652 billion of it—which saved several countries from complete collapse.

And it is Germany that continues to spearhead the effort to prop up the failing economies of Greece, Portugal, Spain and Ireland—placing Deutschland among the most influential European powers.

Because of its fiscal stability and reputation as a nation that foments ideals of peace and human dignity, the country was elected as a non-permanent member of the United Nations Security Council in 2010.

Clearly, Germany is ascendant, and many citizens and politicians believe its outlook is bright.

Rapid Recoveries

The German nation’s revived optimistic attitude sharply divides those who want the country to be free from the shame of its tumultuous history, and those who never want to forget past mistakes—or else be in danger of repeating them.

During the 2010 World Cup, a Lebanese-born shopkeeper who fled to Germany 20 years ago hung a 70-foot German flag outside his store to support the national team. To his chagrin, instead of receiving support for his actions, the flag was repeatedly torn down.

“Police suspect the culprits are members of Berlin’s radical leftist scene,” The Wall Street Journal reported. “For them, the enormous flag is nothing less than a provocation, a repugnant display of German nationalism.”

Although Germany faces ideological challenges, the nation has never been known to take anything sitting down. Throughout its history, it has met and overcome whatever hardships that have come its way with efficiency and forthrightness. This has repeatedly allowed the Deutsch people to recover from devastating circumstances.

In the 1920s, the economy slipped into depression after defeat in World War I, but by the late 1930s, the nation had rallied to again become a major power. After the second world war, when its cities lay in ruins and its shattered citizens queued in long lines for food rations, it was widely felt that Germany would not rise again for a long time, particularly since it was divided into two nations: democratic West Germany and Soviet-ruled East Germany. Yet within 20 years, West Germany underwent a stunning revival, with Berlin, Frankfurt, Munich and Bonn becoming prosperous modern cities with little evidence of previous destruction.

At the end of the Cold War in 1989, the nation faced the daunting prospect of reunification, with many assuming it would take many decades for it to reintegrate beleaguered communist East Germany. Once again, skeptics are being proven wrong, as the once-bankrupt East has not stopped the nation from becoming a major world player.

In every instance, the industrious and efficient Germans prevailed. Unlike other war-torn nations, the country quickly found itself back on its feet. Stores were re-established, restaurants reopened, factories restarted, and national pastimes reinstated.

Turning Tide?

Yet Germany’s ability to bounce-back does not tell the whole story. In almost all instances, the reason the country was in shambles was due to conflicts it had started.

Throughout history, the nation has repeatedly clashed with others, frequently using questionable means to achieve its goals—especially in times of economic crisis.

After each war, Germany said, “Never again.” And for the past nearly 70 years, it has carefully avoided any hint of repeating the events of WWII. But as financial turmoil grips Europe, the country is being forced to take a leading role—a move which has caused some to worry that trends from Germany’s harsher past will begin to re-emerge.

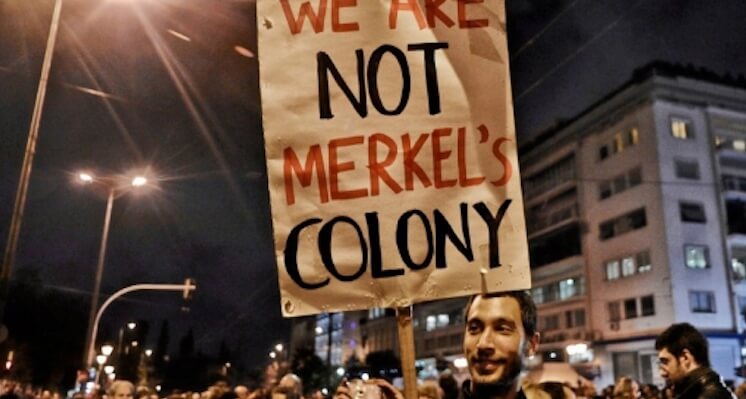

While the nation assisted its European counterparts with billions in bailout funds, it led to growing resentment from Germans fed up with shouldering others’ fiscal mismanagement, prompting German Chancellor Angela Merkel to suggest that financially irresponsible countries be removed from the eurozone.

Germans are also becoming more vocal about once-taboo subjects, with some openly expressing hostility toward immigrants in their nation, clamoring for its 7 million foreign-born citizens—4.3 million of which are Muslim—to return home.

According to a survey by the Frederich Ebert Foundation reported in Der Spiegel, one-third of Germans think the nation “is in serious danger of being overrun by foreigners.” One-third believe that “foreigners have come to take advantage of the welfare state” and that when jobs are scarce, “foreigners should be sent back to their own country.” One-sixth feel “Jews have too much influence,” while more than half want the practice of Islam to be restricted, even though it would violate the country’s constitution. The poll also found that more than one-tenth would like a “Fuhrer” who would govern the country “with a firm hand”!

After years of grappling with immigration problems, Ms. Merkel recently said the concept of multiculturalism in Europe was dead, as printed in a Daily Mail article: “At the beginning of the 60s our country called the foreign workers to come to Germany and now they live in our country. We kidded ourselves a while, we said: ‘They won’t stay, sometime they will be gone.’ But this isn’t reality.”

The article later stated, “The ratcheting up in the political tone, allied as it is with the fears of the population about unemployment and loss of identity, triggered a sharp warning from Jewish leaders in Germany that democracy is under threat.”

Tensions further escalated after a board member of Germany’s federal bank released a controversial book arguing that the failure of immigrants to integrate into society is dumbing down the country—meaning that an unwillingness to identify with German culture has caused a language and education barrier that hinders economic and cultural progress.

“His message has struck a chord among a middle class fearful of declining educational standards and among unskilled workers who are nervous about lower-paid immigrant competition,” Foreign Policymagazine reported, adding, “Since the World War II, xenophobic rhetoric has been barred, both by law and custom. Yet on the German street, resentment about foreigners smoldered, especially so during the Balkan wars of the 1990s when hundreds of thousands of Bosnians and Kosovars arrived in the country…Homegrown Germans, still reeling from the costs of unification, watched aghast, and some of their pent-up frustration is being vented now.” Polls indicate that if the book’s author formed a political party, it would get at least 15 percent of the vote.

Other politicians have entered the fray. Bavaria Premier Horst Seehofer called for an end to immigration, stating in the Guardian that Germany should “deal with the people who already live here” and “get tougher on those who refuse to integrate.”

Familiar Stance

Nationalism, tough talking, fringe groups calling for foreigners to be deported, intolerance and xenophobia have been frequent throughout the nation’s history. To address these and other social troubles, particularly during economic downturns, Germany often places trust in a strong leader to guide it.

Although this approach culminated in the Third Reich under Adolf Hitler, it has happened numerous times before in the nation’s past, including during the eighth century, when a powerful Franco-Germanic kingdom was established. Leaders of this empire considered themselves “defenders of the faith,” as they successfully stopped a Muslim incursion into the continent.

The empire gave way to the rise of Charles the Great—known to the French as Charlemagne and the Germans as Karl de Grosse. This powerful king immediately undertook several military campaigns, which united Western Europe.

Following Charles’ death, Europe fell into disarray and economic despair. After years of chaos, German Otto the Great came to power in AD 936. He was asked by Pope John XII to restore order and defend the church. For his efforts, the grateful pontiff crowned him “Holy Roman Emperor.” This officially united church and state, giving birth to “The Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation”—the First Reich—which officially lasted until the renunciation of the imperial title in 1806.

It was not until several decades before the first world war, when Germany and Italy united from 1871 to 1918, that the Second Reich occurred.

In Wolfgang Benz’s book A Concise History of the Third Reich, he states of this time, “The great power politics of Germany’s second Reich led to the First World War, which Germany entered with illusions of winning a glorious victory…The general goal was to weaken France enough to prevent it from rising again as a great power, and to push Russia far eastward. Other goals included annexation of large tracts of French and Belgian territory, France’s economic dependence on Germany, subordination of Belgium and the Netherlands to German rule, and annexation of Luxembourg.”

“The collapse of the empire in the revolution of November 1918 became a national trauma, characterized externally by territorial losses, oppressive reparations, a loss of status, and military impotence. At home Germans failed to understand the defeat, regarding it as a humiliation and national disgrace. The military defeat and its aftermath triggered the longing for new German greatness in a Third Reich.”

Following its defeat in WWI, Germany made its first attempt at democracy through the Weimar Republic. The system failed miserably, ultimately leaving a record 6 million people unemployed.

With its economy failing and its pride damaged, Germany’s Nazi party and chosen leader, Adolf Hitler, seized the reins of the country promising to establish a 1,000-year Third Reich of peace and one world government. All hopes were dashed as the Nazis resorted to brutal means, sanctioning the deportation and execution of more than 6 million Jews, along with other “undesirables.” At the end of the war, the German fatherland was again brought to its knees.

Perplexing Nation

This gifted, talented country has been somewhat of an enigma. On one hand, it is a nation of intelligent, high-spirited individuals known for their festivals, quality engineering, unparalleled organization and musical heritage. On the other, it has perpetrated some of the most heinous acts of cruelty and barbarity the world has ever seen.

This peculiar paradox was noted by German writer Johann Wolfgang von Goethe: “I have often felt a bitter pain at the thought that the German people, so honourable as individuals, should be so miserable as a whole” (The Life and Works of Goethe).

It has also often been illustrated through motion pictures and books, as well as mused upon by various world leaders trying to understand the nation’s mentality.

In The Germans: Double History of a Nation, author Emil Ludwig writes, “The Romans no more than the Franks or the Italians—indeed, not a single neighbor of the Germans—could ever trust the Germans to remain peaceable. No matter how happy their condition, their restless passion would urge them on to ever more extreme demands.”

Even in the 1943 British film, “The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp,” one character, seeing WWI German officers in a prisoner-of-war camp quietly listening to orchestral music, observed, “I was thinking, how odd they are, queer. For years and years they are writing and dreaming of beautiful music and beautiful poetry. All of a sudden they start a war: they sink undefended ships, shoot innocent hostages, and bomb and destroy whole streets in London, killing little children. And then they sit down in the same butcher’s uniform and listen to Mendelssohn and Schubert.”

No doubt, history reveals that Germany has two personalities—one congenial, the other warlike and aggressive—which have alternated throughout time. What makes the country so capable of incredible ingenuity, yet so prone to destruction?

Why the paradox?

“Germani”

How neighboring nations have viewed Germany begins to reveal the underlying character of its people.

Throughout the Roman Empire, a number of disunited Germanic tribes terrorized Europe with tactics of raiding and pillaging. Julius Caesar led multiple military campaigns to bring them under subjection. He was the first to label this people “Germani.”

In time, the Vandals, the Heruli and the Ostrogoths—all Germanic tribes—would rule Europe.

By AD 455, the Vandals swept through Northern Africa, and eventually attacked and defeated the city of Rome. Their efficient use of piracy, raiding and pillaging still lives on today in the word “vandalize,” which is derived from the tribe’s name.

Twenty-one years later, the Heruli officially occupied Rome—making 476 the official date of the Roman Empire’s fall.

The kingdom of the Ostrogoths (AD 493 to 554), a subset of the Goth peoples, replaced the Heruli.

Many etymology dictionaries trace the word “Germani” to Gaulish origins, claiming it means “neighbor” or “to cry” as in, “one who shouts in battle.” Others note that the most used weapon of these peoples was the spear, and attest that the term comes from the Old High German word for spear, “ger,” which put together means “spear-man.”

The book Surnames of the United Kingdom: A Concise Etymological Dictionary promotes the idea that Germani is probably from the Old High German heri-man, which literally means “army-man.”

Other than “neighbor,” these definitions—one who shouts in battle—spear men—army men—can be summed up into one word: war -men.

Yet it appears that no tribe used this name to describe the whole of Germania, and instead used either Teuton or Deutsch—both generally meaning “people.” To truly understand the German nation, one must dig deeper into the past.

Footnotes of History

British lexicographer Sir William Smith (1813-1893) described the early Germans “as a people of high stature and of great bodily strength, with fair complexions, blue eyes, and yellow or red hair [the Celts were likely living among them at the time]…their chief offensive weapon was the framea, a long spear with a narrow iron point…”

He continues, “Their men found their chief delight in the perils and excitement of war. In peace they passed their lives in listless indolence, only varied by deep gaming and excessive drinking.”

Most historians believe the Germans originated in Europe along the Baltic Sea, but are unclear as to where their peoples derive their ancient roots. Therefore, it is necessary to rely on the footnotes of the past to continue delving into the history of this nation.

Smith reveals a clue to their origin: “The Germans regarded themselves as indigenous in the country; but there can be no doubt that they were a branch of the great Indo-Germanic race, who, along with the Celts, migrated into Europe from the Caucasus and the countries around the Black and Caspian seas [modern-day Turkey], at a period long anterior to historical records.”

Anthropologist Sir Leonard Woolley records in his book The Sumerians a strikingly similar tribe living in the same region: “To the north cast of them, in the Zagros hills and across the plain to the Tigris, there lived a people of very different stock, fair-haired and speaking a ‘Caucasian’ tongue, a hill-people akin to the Guti…” (Some historians equate the Guti with the Goths.)

Woolley continues, stating that after an attempt to take over the Tigris River valley, they “remained in what was afterwards Assyria…”

British ethnologist James Cowl Prichard found that the Greek historian Strabo recorded the same people living south of the Black Sea, whom he labeled the Cappadocians.

“‘The Cappadocians,’ [Strabo] says, ‘of both nations,’ meaning the people dwelling on Mount Taurus under that name, as well as the Cappadocians near Pontus, ‘are termed to the present day Leuco-Syri, or White Syrians, by which term they are distinguished from other Syrians, who are of swarthy complexion [darker skin], dwelling to the southward of Mount Taurus.’”

Greek historian Apollonius called these people Assyrians, saying that they lived near the Halys River (modern-day Kizilirmak River), just south of the Black Sea.

In light of this link, to understand Germany’s national character—and its future—one must then look to the ancient Assyrians.

Past Meets Present

While historical evidence offers competing theories on the origins of the Germans, the Assyria-Germany connection can be furthered by examining this early people’s accomplishments, character and culture. While reading, think of how each could apply to the modern-day Teutonic nation.

- The 1911 edition of Encyclopaedia Britannica states: “The Assyrian forces became a standing army, which, by successive improvements and careful discipline, was moulded into an irresistible fighting machine, and Assyrian policy was directed towards the definite object of reducing the whole civilized world into a single empire and thereby throwing its trade and wealth into Assyrian hands.” Note the words “irresistible fighting machine” aimed at “reducing the whole civilized world into a single empire.”

- James McCabe’s The Pictorial History of the World thoroughly describes the Assyrians, revealing more similarities to the modern Germans. They were “a fierce, treacherous race, delighting in the dangers of the chase in war. The Assyrian troops were notably among the most formidable of ancient warriors…”

- “They never kept faith when it was to their interest to break treaties, and were regarded with suspicion by their neighbors in consequence of this characteristic” (ibid.). In 1939, Nazi Germany entered into a non-aggression treaty with Soviet Russia—WWII began a month later. Also, Poland had a standing non-aggression pact with Germany when it was invaded by Hitler’s army.

- “In the organization and equipment of their troops, and in their system of attack and defence and their method of reducing fortified places, the Assyrians manifested a superiority to the nations by which they were surrounded” (ibid.). The design and engineering of German tanks and aircraft surpassed the allied troops in WWII. They pioneered missiles and the jet engine. Today, they continue to be on the front edge of weapons technology.

- In the book The Course of Civilization Volume I, Joseph Strayer describes Assyria: “They enforced their rule by a deliberate policy of frightfulness, enslaving and deporting whole peoples, and torturing and killing thousands of captives.” This statement could have easily been written about Germany in the early 1940s.

- Carl Engel’s The Music of the Most Ancient Nations points out that “the music of the Assyrians…appears to have attained to a degree of perfection which it could have reached only after a long period of cultivation.” Perfection in music. Think of Bach, Beethoven, Wagner and Brahms.

- The Dictionary of the Ancient Near East states, “Assyrians excelled in road construction and maintenance. Their provincial system was built on good communication, and good roads enabled the Assyrian high command to send infantry and cavalry over long distances to promote stability or conquer new territories.” Germans are also highly skilled engineers, as demonstrated by the world-famous Autobahn.

- Ancient Mesopotamia: Portrait of a Dead Civilization reveals, “In Assyria there was a strong sense of participating in a common and native way of life which repeatedly proved persistent enough to survive military defeats and foreign domination. Who the carriers were who kept the political and cultural tradition and the Assyrian language alive through the eclipses of political power is extremely difficult to say. The right answer would reveal to us the very fountainhead of Assyrian strength and staying power.”

Just as Assyria’s resiliency perplexes historians, so too does the origin of Germany’s mindset.

Key to the Paradox

Crucial early history of the Assyrian people, preserved in the Bible, sheds light on their national character. The book of Genesis records Asshur, father of the Assyrians, in the list of Noah’s descendants (Gen. 10:22).

The Assyrians repeatedly clashed with Israel. For instance, Assyrian King Tiglath-Pileser III (Pul) forced the nation to pay tribute to him (II Kings 15:19-20). The same king returned to take captives (I Kings 15:29; I Chron. 5:6). Later, Assyrian King Shalmaneser captured and imprisoned Israelite political conspirators who had switched allegiances to the king of Egypt (II Kings 17:1-6). The Bible records that Assyrian kings Sennacherib and Esar-haddon also attacked Israel (II Kings 18:13; II Chron. 33:11).

In the book of Isaiah, the Assyrian—German—national psyche is laid bare. Chapter 10 states: “For he [the Assyrian nation] says, By the strength of my hand I have done it, and by my wisdom; for I amprudent” (vs. 13).

Assyria and Germany have a long list of successes and accomplishments, which has led to an ingrained nationalistic pride. (Interestingly, the Hebrew root word for “Asshur” means success.) Look at Germany today: it is strong enough to carry Europe, and other nations come to it for answers because of its financial prudence.

The account in Isaiah 10 continues, revealing the nation’s love for war and tendency to conquer surrounding lands: “…I have removed the bounds of the people, and have robbed their treasures, and I have put down the inhabitants like a valiant man: and my hand has found as a nest the riches of the people: and as one gathers eggs that are left, have I gathered all the earth…” (vs. 13-14).

But why is the German nation wired this way? The answer is found in verse 5, where God reveals His purpose for the nation: “O Assyrian, the rod of My anger, and the staff in their hand is My indignation.” As seen above with ancient Israel, the Assyrian people have long been used by God as a means of punishment for rebellious nations.

Herein lies the paradoxical thinking of the German people: “Howbeit he means not so, neither does his heart think so; but it is in his heart to destroy and cut off nations not a few” (vs. 7). Certainly, while its past is filled with war and violence, Germany “means not so, neither does [its] heart think so.”

Yet the European nation, which is experiencing a renewed sense of nationalism, is not doomed to repeat the cycle of war for all time. The Bible reveals a bright future for it, but the country and its people must first learn valuable lessons, and lay aside deeply ingrained pride and stubbornness. The “rod” used to punish must itself be punished (Zech. 10:11).

Only after this time will Germany be at peace with all other countries and be able to achieve true success as one of the world’s greatest nations. Isaiah 19:24-25 states: “In that day shall Israel be the third with Egypt and with Assyria”—one of the top three nations!—“even a blessing in the midst of the land: whom the Lord of hosts shall bless, saying, Blessed be Egypt My people, and Assyria the work of My hands, and Israel My inheritance.”

It is at this time that the German nation will be able to truly declare, “Never again!”