By Doaa Embabi

Amidst the climactic experience of imprisonment on Robben Island, Nelson Mandela comments on a friendship established with a prosperous colored criminal prisoner saying, “prison is an incubator of friendship-’ (Mandela 280). It is indeed the role of friendship and solidarity during very oppressive times that this article attempts to explore.

The main questions examined are: Is it possible for friendship and solidarity to act as an antidote to the tremendous pain experienced in prison? What are the internal dynamics within friendship and solidarity that help keep a person focused on hope and the achievement of a just cause? How could narrating one’s life experience help in establishing one’s agency — knowing that s/he is backed by supporters and friends? What are the many manifestations that friendship and solidarity take? How could friendship and solidarity be among the safeguards of resistance to, and survival of, oppression?

These questions are addressed with particular reference to two life narratives written by two prominent political figures: the autobiography of the iconic representative of freedom Nelson Mandela: Long Walk to Freedom (1994) and the autobiography of the renowned Egyptian communist leader Fawzi Habashi: Prisoner of All Generations (2011), translated from the Arabic original (2004) by Jano Charbel.

Both works belong to the genre of autobiography or life writing” (Smith and Watson 5). Mandela and Habashi typically position themselves at the heart of the narratives; “they write simultaneously from externalized and internal points of view, taking themselves as both subject and object” (Smith and Watson 5). The events they recount have political, social, and cultural significance. Nonetheless,

“in self life writing the interpreter often recognizes that her ori his choices of what to narrate as formative are subjective and idiosyncratic” (Smith and Watson 5-6). Not only does the writer exercise conscious selection of the material to be included or excluded, but also presents a multi-layered account:

The life writer confronts not one life but two. One is the self that the others see—the social, historical person, with achievements, personal appearance, social relationships. These are “real” attributes of a person living in the world. But there is also the self-experienced only by that person, the self-felt from the inside that the writer can never get “outside of.” The “inside.” or personally experienced, self has a history. While it may not be meaningful as an objective “history of times,” it is a record of self-observation not history observed by others. (Smith and Watson 6)

This account of autobiography stresses the foregrounding of the self as the locus of events and the source of narration. Both Mandela (1918-2013) and Habashi (1924- ) “tell” their own experience of the fight for freedom and of the movements they represent. Thus, as personal histories, such writings cannot be simply regarded as factual historical representation: “While autobiographical narratives may contain information regarded as ‘facts.’’ they are not factual history about a particular time, person, or event. Rather they incorporate usable facts into subjective ‘truth,’ (Smith and Watson 13), i.e. truth that is based on the writer’s perception of the lived experience. As such. “[t]o reduce autobiographical narration to facticity is to strip it of the densities of rhetorical, literary, ethical, political, and cultural dimensions” (13). It is also important to note that, unlike history, life narrative focuses on the personal and individual, even if it incorporates collective cultural, political, or social experiences. Equally relevant to this claim of subjectivity of life writing is the fact that such narratives cannot be measured solely by their fidelity to facts (with the exception of dates of birth, death, implementation of state decisions, etc.). They are ultimately selective, focusing on the self, and engaging in an interactive relationship with the reader—what Smith and Watson call “intersubjective exchange between narrator and reader aimed at producing the shared understanding of the meaning of a life” (16) We do not have a single stable truth delivered unilaterally to the reader:

If we approach such self-referential writing as an intersubjective process that occurs within a dialogic exchange between writer and reader/viewer rather than as a story to be proved or falsified, the emphasis of reading shifts from assessing and verifying knowledge to observing processes of communicative exchange and understanding. It redefines the terms of what we call “truth”: autobiographical writing cannot be read solely as either factual truth or simple fact. As an intersubjective mode, it resides outside a logical or juridical model of truth and falsehood. (Smith and Watson 16-17)

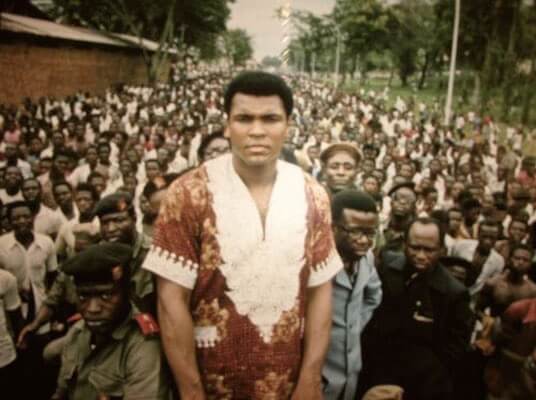

Through this exchange in the life writing by Mandela and Habashi, the reader could observe acts of self-assertion, defiance, agency, t| (|1C pursuit of building a community based on freedom. The historical facts/truths become one component situating the events in their historical context. This is manifest through the employment of details by Habashi and Mandela. One of the key features of their autobiographies is the use of minute details (names, events, places) while supplementing the narrative with photographs taken with family and friends: “The biographical information he (Mandela) supplies and the photographs he displays show Mandela’s attempt to reinforce the communal basis of his text and the fact that the autobiography is as much the story of a community which suffers and resists together as it is his own story” (Alabi 123)— which, to a great extent, also applies to Habashi.

Fawzi Habashi’s memoir bears several affinities to Nelson Mandela’s. In fact, one could say that in the quest for freedom and resistance, there are recurrent motifs in the journey evoking very similar responses from the person going through ail such ordeals for the sake of freedom of expression, and for the right to exist in a society enjoying plurality and free of oppression. The two memoirs were published a decade apart (1994 and 2004) — Habashi’s being the more recent.1 Both men wrote after having been seasoned by experience and driven by the desire to leave to posterity a document representing hope for a better future for their fellow citizens. Although Habashi. unlike Mandela, starts the narrative with the moment of his early youth, touching slightly on his rural background in Upper Egypt, the connections with his origins are never severed. It is true that Mandela’s political career is indeed longer and seemingly more complicated given the nature of the Apartheid system he was resisting and his level of involvement in politics through the African National Council (ANC), the key African organization involved in the fight for freedom. Habashi’s struggle was more ideological; he was a staunch communist who exerted relentless efforts to keep his organization alive and to unify the communists of Egypt. At the same time Habashi was also active in resisting colonialism, and in his capacity as a member of the Egyptian Communist Party, he engaged in most of the critical moments of Egypt’s contemporary history such as the struggle of Egyptians in confrontation with the Tripartite Aggression against Egypt in 1956 after the nationalization of Suez Canal (Habashi 120-27). However, one would tend not to believe that he was seeking a better Egypt only for likeminded fellows. On more than one occasion, for instance, he alluded to his empathy with the political rivals on the far end of the political spectrum, namely, the Muslim Brotherhood (106). Mandela s battle could seem more comprehensive, because he and the ANC had embraced a non-partisan attitude in general, where all the segments of society were engaged. Ultimately, both sought freedom of minds, souls, and physical being from oppression and discrimination.

Both men come from technical backgrounds on which they drew during their imprisonment as a source of asserting their minds: Habashi is an accomplished architect and had a very successful career, while Mandela was trained as a lawyer and practiced the profession with great acclaim before imprisonment. Education, honing one’s skills, and gathering people around learning are all skills that both men continued to nourish, despite the oppressive conditions they found themselves in.

One important common factor that seems to be relevant to sustaining the ability of the freedom fighter to pursue his path is the choice of partner. Habashi talks very early on in his narrative about the way he got introduced to his wife by accident and the fact that he learned about her involvement in one of the leading communist organizations immediately before their actual marriage – much to his heart’s content. Mandela speaks about his various relationships with women, and particularly about the termination of his first marriage on the grounds of an intellectual rift, when he and his first wife Evelyn drifted apart in terms of views of the world and the “struggle.” He also speaks fondly about his second wife Winnie who became a very strong supporter of the cause of blacks in South Africa and a leader in her own right, bearing her share of harassment by the authorities for so long. Despite the difference in scale and scope of the struggle, the ensuing persecution, and the fame that accompanies the whole story, Soraya Habashi and Winnie Mandela – each in her own sphere – were a strong source of inspiration and support for their husbands. Both men speak fondly of their supportive wives and their texts evoke a sense of profound appreciation that they had such strong partners during very difficult times. These successful marital relationships that stood the test of time, the forced separation, the poverty and confusion, all com¬pose one component of the secret ingredient that makes the experience of both Mandela and Habashi so poignant.²

This same ingredient also includes being surrounded with good friends and acquaintances (even if by mere chance during imprisonment) and the ability to draw reassurance from their collective existence. It is through solidarity that imprisonment does not seem to be a futile endeavor, and the whole experience of incarceration stands in great contradiction to the ability to create some-thing worthwhile from the painful nothingness that the authorities attempt to impose (as will be shown in more detail later in the article). Both Mandela and Habashi arc human beings after all and, despite the heroic and audacious nature of their pursuits, they undergo doubt, which makes their experience all the more human. This article does not claim that they were not traumatized; quite the contrary. Indeed, it is because of – even if partly – their resilience and the support of their troupe of friends, family, colleagues, and acquaintances that they were able to keep a positive frame of mind and to leave to posterity a living document of the importance of hope and the belief that justice will prevail.

The traumatic experience related in the two memoirs is initially quite personal, despite the fact that suffering and victimization were anticipated by both Habashi and Mandela. Since they were the result of calculated political actions, the ramifications were obvious, if not planned. This article has at its core interest this personal painful experience and its overcoming through friendship and solidarity in the wider sense of the word. It is not focused on the collective trauma of the society, of which the individual experiences of both Habashi and Mandela are inextricable. It is not focused on what Dominick LaCapra dubs “trauma transformed and transvalued into a legitimating myth of origins,” when trauma “serves an ideological function in authorizing acts or policies that appeal to it for justification” (xii). The article does not adopt the concept of trauma as a psychological “wound” (as the Greek origin of the word suggests), nor does it focus on the symptoms associated with this condition such as dissociation and the inability to recount the story, because this is not the situation of the two narratives studied. The use of the word, however, is limited to qualifying specific painful incidents within the larger framework of imprisonment that both

My Self and My Friends

A discussion of the impact of friendship implies a reflection on the position of the self vis-a-vis the “other” – which includes friends. Dan Zahavi provides a relevant view on the constitution of the “self’: “[O]ne cannot be a self on one’s own, but only together with others. Indeed, on this account, the self is best described as a social construction, something that is more a matter of politics and culture, than of science and nature” (145). Thus, the self is not only something innate or given, it is a state realized upon interaction with others within influential contexts. Friendship, as such, could be viewed as one of the formative influences on the “self,” since friends are among the key categories of the “other.” In their autobiographies, Mandela and Habashi provide accounts of the constitution of the self throughout their journeys, where the relationship with the other plays a seminal role.

As used here, friendship is rather a loose form of commitment that does not necessitate many procedures or even proclaimed allegiance. It is an emotional bond that enhances life (Telfer 238-41). Friendship refers to the various forms of coming together, collaboration, fellowship, and support. Conceptually, the notion of friendship adopted derives from the Western philosophical tradition, which has been discussed profusely from various perspectives: politics, charity, virtue, religious affinity, and oth¬ers.³ However, revisiting Aristotle’s take on friendship in his treatise Nicomachean Ethics (Books VIII and IX) is particularly engaging for the purposes of the discussion of friendship. In his long inventory of the moti-vations informing friendship, Aristotle discusses the importance of this bond at times of prosperity and adversity, and argues as follows:

Do we need friends more in good fortune or in bad? . . . the very presence of friends is pleasant both in good for-tune and also in bad, since grief is lightened when friends sorrow with us. Hence one might ask whether they share as it were our burden, or – without that happening – their presence by its pleasantness, and the thought of their grieving with us, make our pain less. (n. pag.)

According to this argument, a friend is somebody whose presence is comforting and pleasant.4 The idea here is that friends are important for all the support they offer, which ranges from the broad spectrum of actual shouldering of pain down to offering their pleasant company.

Emphasizing this core quality of friendship, Elizabeth Telfer speaks in the twentieth century about its “values,” stating that one value could be helping the friend bear the burden of an unpleasant experience: What we do may in itself be unattractive, but become fun – indeed, be turned into a kind of game – when shared with a friend (239). This could apply at large to imprisonment with friends, where the experience is unpleasant for all but made easier in the presence of people close to those imprisoned. She also argues, in agreement with Aristotle, that “friendship is life-enhancing, it makes us have life ‘more abundantly”’ (239). She explains the phrase “life enhancing” as a form of relationships that makes the person “feel more” in terms of emotions because due to this tie with people we have a stake in the world. Friendship also improves our activities due to the larger sense of commitment one experiences when one performs an activity in the company of a friend. Moreover, friends experience “enhanced pleasure” when they engage in a joint activity (240). Thus, as used in this context, friendship is presented as a bond that is helpful at times of adversity and prosperity alike, because it is rooted in sharing materially and emotionally. It is a bond that helps the person stand the test of trying times.

This claim that friendship enhances our experience of life is indeed true in the cases of Mandela and Habashi. This article will not provide an exhaustive inventory of the many friends, fellows, acquaintances, comrades, colleagues, and inmates both had throughout their long and rich journeys. However, two indicative instances are cited as examples of the power of friendship in helping one’s existence and better understanding of the self. Both incidents are also connected to a very significant event, namely, the recording in writing of the events of imprisonment. Habashi was subjected to brutal torture while serv¬ing time in El-‘Azzab Prison (1959)-to which he refers as El-‘Azaab, the Arabic word for torture (150), as it reminded him of the infamous prisons and concentration camps of Nazi Germany (155). He was brutally whipped (after having been stripped naked) on account of establishing a secret cell among his comrades from the Egyptian Communist Party and for refusing to tell the name of its leader. Upon attempting to walk back to his cell instead of being pulled on the ground—to save himself the pain of having his wounded naked body further scraped off against the ground the Police Investigations Officer, Abdel Aziz Shaker, ordered a bag of salt dissolved in a bucket of water and had his underwear soaked in this water then squeezed

on all the open wounds of Habashi’s body. They had hoped that by doing this Habashi would perish due to a heart shock, which he actually experienced: “I felt a major shock inside of me. Like I had just entered the gates of hell” (160).

Nevertheless, Habashi survived the ordeal. He was well taken care of by his friends who cleaned his wounds and gave him a silk robe to wear. However, more importantly, his friends commemorated this incident in their own memoirs, making his ability to withstand torture and to survive experienced “more abundantly” in Telfer’s terms (239). He specifically recalls the reference made by his comrades to this act of torture in their memoirs and autobiographies: The Bare Feet by Taher Abdel Hakim and Memoirs of a Political Prisoner by El-Sayyed Youssef. To Habashi, the great triumph lies in the fact that “the act of torture perpetrated against me was recorded in history, from the per-spectives of different authors. In my case, history did not neglect to mention the details of this incident” (162). Recording for posterity is key in Habashi’s narrative. It is as if he traded the pain and trauma with the ability to “tell” the story of survival. The redeeming quality of the event is the triumph and the acknowledgment, despite the scars of torture documented by the forensic medical examiner in 1975 “after fifteen years from the date on which this act of torture was perpetrated!” (161). This reflection on the ordeal of torture is indeed one of the climactic points in the text because it connects to one of the important notions of selfhood, namely empathy:

[E]mpathy is what allows me to experience other experiencing subjects. It entails neither that the other’s experience is literally transmitted to me, nor that 1 undergo the experience I observe in the other. Rather, to empathically experience . . . necessarily differs from the way you would experience the emotion if it were your own. (Zahavi 151)

In this sense, empathy not only helps the empathizer to realize himself through assimilating the experience of the “other” – the friend in this case – but also boosts the faith of the person empathized with that their experience is recognized.

Mandela similarly records the support and encouragement he received from his friends Walter Sisulu and Ahmad Kathrada urging him to write his memoirs. They proposed the idea to Mandela in 1975. In the true spirit of enhancing life, they built a convincing argument:

“Kathy noted that the perfect time for such a hook to be published would be on my sixtieth birthday. Walter said that such a story, if told truly and fairly, would serve to remind the people of what vve had fought and were still fighting for” (415). They not only proposed the idea, but also devised a very intricate plan and implemented it with the help of other friends, which led to Kathrada’s loss of studying privileges when the authorities discovered the manuscript. However, this manuscript written on Robben Island served as the backbone of Mandela’s autobiography. Both accounts prove that friends are there to support but also to enrich the potential of life, and to celebrate the abilities and triumphs of the friend as well.

The Wife as a Friend

Philosophical literature on friendship dating back to Aristotle and earlier draws a clear distinction between friendship and other types of relationships such as kinship or marriage. As mentioned earlier, friendship is perceived to be a very unique state that involves closeness to a person without being necessarily based on institutional ties whatsoever, such as contracts (as in the case of marriage). However, reading the two autobiographies reveals the very special relationship both Mandela and Habashi had with their wives. Therefore, the article approaches this social relationship from the perspective of friendship, because neither Winnie nor Soraya were solely wives: “[F]riendship seems to involve reciprocated goodwill and sonic element of utility, pleasure, and moral intellectual virtue” (von Heyking and Avramenko 5), and such aspects were fulfilled in the marriages of both Mandela and Habashi.

Habashi’s narrative highlights the special relationship he had with his wife Soraya, who was not only his wife, but also a comrade. Out of the several details of his early youth and career, Habashi decides to recount how he was introduced to her, proposed, and then ultimately got married to her (29-35). Throughout the rest of the book, the letters exchanged between Habashi and Soraya punctuate the journey of political struggle and imprisonment. The letters reveal a very special relationship of camaraderie. In addition to the practical information (news from lawyers, news about the extended family, requests of items to be brought to prison, and the like), the letters are also messages of fine love and affection. They act as a bridge between the two lovers and fighters. Habashi does not even justify or explain the inclusion of the letters as part of the text. They appear saliently in the narrative, creating a very interesting interplay between the personal and the political spheres of Habashi’s life, while at the same time highlighting the powerful psychological support they provide during hard times.

Very early on in their marriage, the leadership of Soraya’s communist organization HADITU threatened the new bride that she either convince her husband to join the organization or desert him. Habashi was concerned that Soraya would give up under such a pressure.

Naturally Soraya refused to abide by her leadership’s attempts at forcibly recruiting me. Later, whilst in detention, she wrote to me: “Despite our difference in organizational affiliations we shall, nonetheless, fight together against the forces of injustice.” This letter made me happy and proud of Soraya, for she proved to me that our relationship could overcome all the distorted tactics of these organizations. My soul mate Soraya was beyond such pettiness. (41)

Thus, at the outset of the narrative, Habashi establishes the bond that he had with his wife and that it was loftier than “petty” organizational affiliation. Moreover, it becomes clear that it is not just a familial bond, but one that is linked to the struggle against “forces of injustice” (Habashi 41).

During his imprisonment in 1949 in El-Taur, Sinai (which was very isolated at the time), Habashi speaks of waiting for his wife’s let¬ters with such anticipation that he takes the letters to a quiet place to read them without being disturbed, “for I was both hungry and thirsty for love and life” (77). The manner in which Soraya reciprocates reflects her intuitive understanding of her husband’s need to be reassured of her love. She always starts her letters with the expression “My beloved Fawzi.” Also, she starts a letter sent on August 15, 1948, during his first term served in the Huckstep Prison Camp, with a very romantic opening: “I have assumed the seating position that I always take while writing my letters to you. … I can hear Fareed El-Atrash on the radio singing ‘together … together … come on together.’ And I wish that we could be together” (83). This sense of companionship permeates the narrative. Habashi, thus, chooses to conclude his eventful life story with his expression of contentment for being surrounded with a great family. at the top of which comes his beloved wife Soraya (Habashi 275).

Mandela’s marriage to Winnie was also based on attraction and took place amidst his first trial, being charged with treason (1958). Unlike Soraya who was politically active before her marriage, Winnie became a seasoned political activist in her own right after her marriage to Mandela. Friendship in the case of Mandela and Winnie was reciprocated and sophisticated. In a true spirit of friendship, he speaks of Winnie’s ability to become politically involved in goodwill: “others saw her as ‘Mandela’s wife.’ It was undoubtedly difficult for her I did my best to let her bloom in her own right, and she soon did so without any of my help” (197). Both Mandela and Winnie had to survive many ordeals, but she proved to be the right “witch” at the time for the “wizard” of the struggle (188).6 Mandela’s account of his interaction with Winnie is marked with the admiration and support one has for his comrade-in-arms. Early on, when she joined the ANC’s Women’s League protest against the use of passes for women, Winnie was imprisoned in Marshall Square (the police station). In his capacity as lawyer, Mandela went to provide legal aid to the detained women. There he managed to see her and commend her resilience. The exchange of emotions and few words creates a complete image of supportive companionship despite the disheartening context: Winnie “beamed when she saw me and seemed as happy as one could be in a bare police cell. It was as if she had given me a great gift that she knew would please me. I told her I was proud of her” (193). Mandela seems to have been drawing comfort from the reassurance that Winnie is “resilient.” He comes back to this very same thought about her when she had to suffer internal banishment by the authorities in the destitute area of Brandfort (1977) where she was forced to live under very harsh conditions. Mandela comments on the pain he experienced because his wife had to suffer that much, and because he would not be able any more to “imagine” her undertaking normal everyday activities that he usually would be able to conjure up when she still lived in their home in Soweto. Nonetheless, this image of pain is juxtaposed with the closing comment he makes about this story of banishment, praising Winnie’s resilience once more:

Winnie is a resilient person, and within a relatively short time, she had won over the people of the township, including some sympathetic whites in the vicinity. She supplied food to the people in the township with the help of Operation Hunger, started a créche or nursery school for the township’s children, and raised funds to create a medical clinic in a place where few people had ever seen a doctor. (430)

In the true vein of friendship, Mandela speaks with admiration about his wife’s accomplishments under such dire circumstances.

It is as if Mandela draws on this trust – built and tempered by time – in his wife’s capacities to invoke the personal strength he himself needs for surviving the pressure of oppression. The strength invoked by friendship was not only a mental image, conjured at Mandela’s convenience of Winnie at home or Winnie defying oppression by being involved in community work, but it was also the outcome of actual support. When Mandela was in remand in Johannesburg Fort during the Rivonia Trials, he was visited by Winnie who brought him a pair of expensive pyjamas and a silk gown. To Mandela, though this gift was quite “inappropriate” for jail, he saw it as a token of “expressing her love and a pledge of solidarity” (227). Mandela, in a true spirit of friendship, “assured her of the strength of [their] cause, the loyalty of [their] friends, and how it would be her love and devotion that would see [him] through whatever transpired” (277). Both partners needed one another’s support and reassurance and they were to provide that for as long as they could.7

The Worth of Friendship in Isolation

One of the proofs of the power of friendship for both Habashi and Mandela is defined by an absence; both reminisce in so many tones and instances about one of the most poignant aspects regarding imprisonment and harassment by the oppressors, namely, forced isolation. This isolation manifested itself in various forms such as solitary confinement (as a disciplinary measure), single-cell imprisonment (in the case of Mandela), going underground and staying hiding (even if by choice), and banning (i.e., restrictions on mobility (as in the case of Mandela and his wife Winnie). Among many other issues, such acts of “isolation” mainly deprive the person of the free company of friends. The isolation puts the person under tremendous mental pressure, stripping him/her of the ability to feel confidently free. On living underground for about a year before his arrest, Mandela writes: “Living underground requires a seismic psychological shift. . . . You cannot be yourself; you must fully inhabit whatever role you have assumed” (232). In turn, you cannot be as open and as trusting as you would wish. One could lose all the comforts of friendship with this decision, due to the feeling of fear of being caught. Habashi comments on his arrest after having stayed in hiding for long: “I had grown tired of being chased around, of not being able to see Soraya or our children (144). Living underground drained the capacity of both to lead a normal life.

This sense of isolation is also usually doubled with imprisonment in remote places. Habashi experienced this twice: once in one of his early encounters with detention in the then (1949) town of El-Taur, Sinai, which had nothing ‘except tor a medical quarantine unit for those making the pilgrimage to and from Mecca” (70), and where he and his comrades felt as if they were in exile, as their only connection to land was a haggard ferry boat that would arrive every month with their letters and parcels. The second time was under even harsher conditions, when he was imprisoned in El-Wahat El-Kharga Prison in the heart of the desert, where the harshness of the environment and bad treatment aggravated the experience of isolation. Mandela expresses a similar sentiment after having been transferred to the prison on Robben Island: In Pretoria, we felt connected to our supporters and our families; on the island, we felt cut off, and indeed we were” (338). However, both Mandela and Habashi realize that the main consolation in this dismal experience is that, after all, the friends were together. Mandela continues the thought saying: “We had the consolation of being with each other, but that was the only consolation” (338; emphasis added); whereas Habashi sees this utter isolation as an exercise in “human endurance and determination” and more importantly this experience in El-Wahat and other camps ‘‘served to unite us communists (and non-communists alike)” (172). Thus, the intentions of the authorities were defied by the sheer fact that Mandela and Habashi suffered but with friends.

Solitary confinement is the ultimate form of isolation compared to other situations. It denies the person one of the key aspects afforded by friendship, i.e., the assurance and recognition of the self that a friend provides: “Insofar as the other person affirms me as a friend, the other person is also reflecting back to me an approval and endorsement of who I am” (White 86). This pleasure and need for endorsement are devoured in solitary confinement. Isolation was meant to break this resolve secured in the company of friends and comrades: “I found solitary confinement the most forbidding aspect of prison life. . . One begins to question everything. Did I make the right decision, was my sacrifice worth it? In Solitary, there is no distraction from these haunting questions” (Mandela 363). Through their ability to share the burden of pain, and the pleasure they offer with their sheer presence, friends deflect “the haunting questions,” and through their “endorsement” of one’s presence, they provide the required reassurance that the struggle is worthwhile.

Accordingly, the Egyptian and the South African authorities exercised power as envisaged by Foucault:

a power relationship can only be articulated on the basis of two elements which are each indispensable if it is really to be a power relationship: that “the other” (the one over whom power is exercised) be thoroughly recognized and maintained to the very end as a person who acts; and that, faced with a relationship of power, a whole field of responses, reactions, results, and possible inventions may open up. (789)

The resisting blacks or the Egyptian opposition were recognized by the state as “free” acting subjects, and as such were the target of the exercise of power. One of the actions employed by the state exerting its power is the forced separation imposed socially: the case of the Apartheid which is “codification in one oppressive system of all the laws and regulations that kept Africans in an inferior position to whites” and literally meaning “apartness” (Mandela 97). Another form was banning, the “psychological claustrophobia that makes one yearn not only for freedom of movement but spiritual escape,” whose “insidious” effect was that “at a certain point one began to think that the oppressor was not without but within” (Mandela 126). Politically, arbitrary imprisonment and solitary confinement of opponents were another form of power exercised by the state. This time the carceral institution is used to make confinement not only “legal” but also mental and physical. Thus, power becomes “a way of acting upon an acting subject or acting subjects by virtue of their acting or being capable of action. A set of actions upon other actions” (Foucault 789). However, no matter how pervasive such actions are, since the main premise of Foucault’s argument is that those on whom such power is exercised are “free” – despite the condition of physical imprisonment at times – “recalcitrance” is always possible (790). One counteraction could be recalling the memory of warmth of companionship and reassurance of friendship to boost one’s morale. In fact, the comments made by Mandela and Habashi on the forms of isolation exercised against them serve as further proof of the deep appreciation they had for friendship and the value they ascribed to it. Such comments also confirm the possibility of response upon the action of alienation imposed by the state.

The “Other” End of the Spectrum of Friends: The Police

One of the problematic areas in the narratives of Habashi and particularly of Mandela is the paradoxical relationship between “self” (personal or collective) and inimical “other.” Both narratives show a great degree of tolerance towards the “enemy” to the extent that in some cases they corroborate von Heyking and Avramenko’s statement: “As Socrates indicates in the Lysis, regarding friendship as a relationship of dissimilars implies that one befriend one’s enemy, thereby rendering ‘friend’ and ‘enemy’ meaningless” (15). Although the boundaries between friend and enemy do not fully disappear, the relationship between prisoner and authorities (warders, officers of all ranks and positions, and even color as in the case of Mandela) is paradoxical.

However, this controversial relationship between self and other in the context of imprisonment could be better understood against the overall goal of the struggle – namely, achieving justice for all. Mandela and Habashi embarked on a quest for a society that provided equal opportunities for all, and in which all members enjoyed a harmonious life:

Mandela situates his autobiography within his communally based society, and he defines himself in relation to the community. By doing so, he succeeds in claiming his individual subjectivity within the framework of the collective. That claim allows him later to champion the attempt of the community to assert a collective subject position in contrast to the object position the community is reduced to by apartheid. (Alabi 124-25)

Similarly, Habashi, as described by his contemporaries, asserted his own individual commitment but through the collective. According to the testimony of the Egyptian socialist novelist Sonallah Ibrahim—who encountered Habashi in El-Wahat Prison—Habashi “is also characterized by modesty, humility, self-sacrifice, and unwavering determination. . . . [He] was trusted by all. He was a dove and a peace broker amongst those with conflicting political viewpoints” (qtd. in Habashi 286). Mahmoud Amin El-‘Alem further maintains that “[t]he path led by Fawzi Habashi – in terms of his struggle for freedom, justice, progress, and humanity – is a shining example for all Egyptians and for all political activists. He is an individual who has sought to build a socialist nation, along with a world of humanity” (qtd. in Habashi 278). Thus, it is within this communal worldview, where human dignity and humanity are pursued, that the hostile “other* is envisaged and situated. Habashi and Mandela contemplate incidents along the path of imprisonment and examine the human face of their “other.” Mandela’s plight could be considered more complicated than Habashi’s. Mandela had to deal with a multi-faceted “other” in his fight for freedom: He had to grapple not only with the discrimination exercised by white warders, but also by the blacks. Commenting on the black policemen who helped them, Mandela writes: “They were decent fellows and found themselves in a moral quandary. They were loyal to their employer and needed to keep their jobs . . . but they were very sympathetic to our cause” (117). Thus, Mandela acknowledges that some black warders were caught in a dilemma: While sympathetic with their kin, they were employed by the whites and had to abide by their orders. However, despite this sense of community that enables Mandela to empathize with the “enemy,” there are instances where he could not. As much as he finds an excuse for the harsh treatment by the black warders, he could not understand the motive behind the betrayal by Bruno Mtolo, a former MK leader of the Natal region, during his testimony at the Rivonia trial: “I was bewildered by Mtolo’s betrayal…. It is possible, I know, to have a change of heart, but to betray so many others, many of whom were innocent, seemed to me inexcusable” (312).

Small gestures such as offering or accepting food are interpreted by both Mandela and Habashi as attempts at establishing some communication and identification between guard and prisoner on the basis of the common humanity they share. Upon Habashi’s arrest in 1959 against the background of rounding up communists, he recalled another comrade of his who had already fallen in the hands of the police: Mahmoud Othman. As Habashi was taken to the prison of El- Qal‘a (Citadel), he learned of the brutal torturing of his colleague and decided to undertake an act of defiance by asking the prosecutor interrogating him to file a complaint and to open an investigation of the incident. He was given pen and paper and waited for the Prosecutor General to arrive to have the report presented to him. However, the Prosecutor General flew into a wave of rage and tore the paper into pieces. Habashi did not cower. He rather shouted back that the “state has overridden all the rules of law” (148). At that moment,

One of the younger police officers accompanying the general prosecutor pulled me aside by the hand, while trying to conceal the grin upon his face. I believe that this grin was attributable to the fact that this junior officer, like so many others, had grown weary of the arrogance of such big statesmen. (148)

The officer then treated Habashi to a cup of tea in one of the close by cafes, which brought so much joy to the freedom-loving prisoner: “This ‘tree’ life contrasted sharply against a prison life characterized by confinement in bolted cells, and a lack of ventilation” (148). This and other instances vest the officers with a human face. Despite the fact that Habashi feels that the state played an oppressing role for the most part, he could still appreciate the small acts of kindness by some of the officers, and as such brighten up.

Similarly, Mandela recounts a story of a white warder on Robben Island who was very hostile to the prisoners (which compromises their ability to communicate as they would like). They decided to befriend him and asked one of the “comrades” to do so. and they succeeded. One day, this warder threw an extra sandwich on the grass for the inmates to take. For a moment, they were taken aback by the gesture and were at a loss. They ultimately decided that this “was his way of showing friendship” (365) and accepted the sandwich. When they decided not to antagonize the warder, he wanted to listen to what they had to say. Ultimately, he was drawn to their egalitarian argument saying, “It makes more bloody sense than the Nats (the ruling party]” (366). Thus, sharing food symbolizes signs of friendship and welcoming, forging connections while promising some hope.

Brutal force used by the police and prison officers is obviously not openly challenged from within. However, empathy was shown in some occasions, which to a low-spirited prisoner is very uplifting. Habashi comments on the compassionate remark made by a local police officer escorting him, and others, by train (his body bloodied after having been brutally beaten the day before) to El-Kharga Prison saying: “When he saw that my whole body was covered with strips of cotton, this officer whispered into my ear (with a heavy Upper Egyptian accent): ‘They are not humans, they are monsters!’ This officer’s words actually served to raise my spirits significantly” (165). This is a moment of utter identification between victim and officer, where the words combined with the accent-reminding Habashi of his own- soothe the physical pain experienced as a result of the wounds.

The encounters with the police and prison officers are predominantly unpleasant, as it were, ranging from stringent instructions and disciplinary measures to brutal lethal torture. Thus, there is no question in the two narratives about the fact that the balance of power is lipped to the side of this force. However, according to Habashi, this situation witnessed a turning point, where power was in the hands of the prisoners and the Prison Commissioner (Farid Shenaishan) was under their mercy. The Commissioner’s son was dying of food poisoning and the prison doctor was on leave. He and his family were in the middle of the desert, hundreds of miles away from any medical service. He had to turn to the physicians in captivity, who managed indeed to save the son from the snares of death. This experience was a tipping point in the officer-prisoner relations. The sense of human appreciation won: ‘“Shenaishan the Monster’ was replaced by a far gentler personality” (175). Not only did the Commissioner loosen his grip over the prisoners, but even allowed them to reclaim a plot of land and upgrade a neglected water spring, making a water tank which they even started to use as a swimming pool. This is similar to the sentiment expressed by Mandela towards one of the harshest commanders on Robben Island, Colonel Piet Badenhorst, who deliberately made the lives of Nelson Mandela and other inmates very difficult. After having been so mean for almost a couple of years, and probably based on complaint made by prisoners led by Mandela, Badenhorst was to be transferred from the island. Upon leaving, Mandela was called to the main office of prison where Badenhorst said, “I just want to wish you people good luck” (402). Mandela contemplates this shift in behavior by asserting essential goodness that all human beings share:

[He] had revealed that there was another side to his nature, a side that had been obscured but that still existed. It was a useful reminder that all men, even the most seem¬ingly cold-blooded, have a core of decency, and that if their heart is touched, they are capable of changing. Ultimately, Badenhorst was not evil; his inhumanity had been foisted upon him by an inhuman system. He behaved like a brute because he was rewarded for brutish behavior. (402-03; emphasis added)

Mandela and Habashi were able to overcome the barrier of hatred fed by the painful experience they went through. Even if they do not befriend their “enemy” they are able to see the essential humanity latent in this person.

Solidarity, Agency, and Resistance

Conceptually, solidarity is different from friendship. As discussed earlier, friendship is rather individual and certainly personal, whereas solidarity is more communal. Friendship does not necessarily entail action, while solidarity usually does. This article adopts a simple definition of solidarity as: “a relation forged through political struggle which seeks to challenge forms of oppression” (Featherstone 5). Accordingly, solidarity, unlike friendship, is centered on a cause. But similar to friendship, it is a conscious act of coming close. Unlike friendship, it necessitates that one subscribes to a cause and share a frame of mind supportive of this cause. However, reading the autobiographies of both Mandela and Habashi shows that friendship alone is not sufficient for surviving the mental and physical pain experienced. Solidarity is an essential component in the larger endeavor of both. It is important for enabling them to extend resistance to oppression to the microcosm of prison. It is crucial for helping them and other inmates transcend the madness of wasted time with meaningful activities. Most significantly, it is solidarity after all that reassured both Habashi and Mandela at moments of utter doubt that the struggle was worthwhile.

Nonetheless, any treatment of solidarity in both texts needs to be situated against the background of agency and resistance. For the purposes of the discussion in this article, resistance “refers to intentional, and hence conscious, acts of defiance or opposition by a subordinate individual or group of individuals against a superior individual or set of individuals. Such acts are counter-hegemonic but may not succeed in effecting change” (Seymour 305). The most important feature of resistance, therefore, is intentional defiance of injustice. Certainly, in the case of Mandela, a major change is achieved because he ultimately accedes to power. In the case of Habashi, however, the impact of his ideological opposition was more subtle, contributing – together with the many tributaries of resistance—to the struggle by Egyptians against oppression. As Ismael and El-Sa‘id maintain, despite the fact that the communist movement never achieved any formal power:

In a very concrete sense, the communist movement has brought the public into the political process in Egypt. Through its various organizing and mobilizing activities, the movement penetrated into the popular classes and politicized their social problems. In this way, the movement played a vanguard role in politicizing groups and issues. It would have been impossible to envisage the evolution of resistance in the Egyptian society without the impact of the communists. (157; see also 152-57)

Habashi’s personal resistance is but an extension of the spirit guiding the communist movement in Egypt. Despite the fact that the movement had its own structural problems and issues in its relationship with the state, its existence bore on the consciousness of important segments in society: labor and. to some extent, peasants.

Solidarity is also different from friendship in that it involves the group. Given the context of resistance, solidarity is closely connected to the conscious decision exercised by the “self’ to become part of the “we”:

the we is not some entity that is observed from without but, rather, a distinct way of being with and relating to others. . . . One might by birth (right) be a member of a certain group (family, class, nation, ethnicity, etc.) regardless of whether one knows or cares about it, just as outsiders might classify one as a member of a certain group quite independently of one’s own view on the matter. But this kind of group membership doesn’t amount to a we. For a we to emerge, the prospective members have to identify with the group. It is their attitudes towards each other (and towards themselves) that are important. (Zahavi 156-57)

Certainly, Mandela’s narrative is rich in such examples where he himself opts to identify with a given group or other throughout his journey. However, it is noteworthy that Mandela provides an account of specific White people whose solidarity he believed was invaluable: Alan Paton, Helen Suzman, and Bram Fischer. But Fischer’s solidarity is particularly underscored. The first encounter Mandela had with Fischer (a part-time lecturer) was at the University of Witwatersrand. Fischer was the “scion of a distinguished Afrikaner family,” both affluent and politically influential: “Although he could have been a prime minister of South Africa, he became one of the bravest and staunchest friends of the freedom struggle” (79). Fischer, as such, opted to belong to the “we” of the freedom fighters and resistance. Therefore, he was wholeheartedly welcomed by them. This earns him a testimony by Mandela to his unmatched courage and nobility, putting him in a niche of his own throughout the entire narrative. Upon learning of Bram’s tragic death while in prison, Mandela contemplates his unsurpassed solidarity to the cause: In many ways, Bram Fischer, the grandson of the prime minister of the Orange River Colony, had made the greatest sacrifice of all (41 1). To Mandela, the power to act and the belief in his capacity to act were well supported. However, what makes Fischer superior is his double alienation: once as a freedom fighter in a system rooted in discrimination, and another time as a white man defying his own people:

No matter what I suffered in my pursuit of freedom, I always took strength from the fact that I was fighting with and for my own people. Bram was a free man who fought against his own people to ensure the freedom of others” (41; emphasis added).

Solidarity also comes with qualms. Although Habashi chooses consciously to be a member of the communists in Egypt, he still desired that the communist movement be incorporated within the larger “we” of the newly-freed nation. Similar to many Egyptian intellectuals of his time involved in opposition, his active political career coincides with the full period of Nasser’s regime. Thus, he dedicates a long section of his account to the forms of political engagement during that time, and the entailing imprisonment. One of the most important aspects about the story told is that, unlike the ensuing terms of imprisonment served at the time of Anwar Sadat, the term Habashi served during the years 1959¬1964 (coinciding with Nasser’s reign) was the harshest. Nonetheless, throughout his account of that period, Habashi provides proof that the communists exercised solidarity with most of the national causes experienced by Egypt. He focuses on the role they played in the liberation struggle. Though Mandela follows a similar path, the reader cannot help noting that, despite all the differences in the approaches adopted by diverse black resistance movements until the dismantling of Apartheid, there was one ultimate enemy. Habashi’s situation is more delicate, as the “other”/ “enemy” soon shifted – post 1952 – from the foreign colonizer to the ideological other. Hence, this part of Habashi’s career fluctuates between discontent at such political blunders as blocking all channels of legitimate opposition (100,101,103,112, and 204), on the one hand, and admiration of some of the achievements of the Nasserite era, on the other. Habashi concludes the chapters set during the rule of Nasser with this statement: “For the Egyptian people had realized that, even though some serious mistakes were perpetrated, the years of the Nasser Regime were characterized by dignified confrontation of colonialism. . . . Nasser was simply a great national hero” (210). Habashi underscores communist solidarity expressed actively during the 1956 war by France, the UK, and Israel against Fgypt. Over the stretch of four pages, he illustrates the acts of bravery by the communists and their contribution to the war effort (122-25). He also cites the memoirs of other communists who provided accounts of their personal and the whole movement’s contribution to resistance. His and other testimonies he cites not only document the com-mendable acts of members of the communist groups, but also provide an alternative narrative for the non-ideologized Egyptian, that the communists were not enemies of the state, but part of the struggle for true freedom from oppression. Although he does not dwell much on the encounters between communists and the ideological “others,” his narrative focuses on the efforts towards rebuilding the country on the basis of freedom and the communal spirit, regardless of ideological differences.

The year 1959 marks the climax of the intricate relationship between Habashi and his political “other,” Hunted by the police, his wife in prison, and almost the entire communist political leadership locked up (142), Habashi interrupts the narrative of the actions he undertook to help those in prison and their families, while trying to preserve his own freedom, with a digressive thought on the achievements of the revolution (the Aswan Dam and Arab national unity for instance [142-43]). Similar to Mandela, Habashi has a very clear position. But he could not align himself with the crimes committed against his comrades in the name of protecting the state and the Revolution. Indeed, Habashi is sufficiently fair to give the “other” credit for all the good deeds: “Yet the blood would drip from thorns of Egypt’s blossoming rose” (143). Opposing the crushing of human dignity was for him far more paramount to any act of political solidarity to appease the ruling regime.

If we are to agree with Foucault that power is “actions upon actions,” if power is only exercised on “free” subjects, and if the very existence of power means inherently “insubordination” (789-94), then resistance to power needs to be understood against “agency.” Agency here is not simply having “free will” but the manner in which one can “exert will,” which is what controls and informs aspirations and actions (Hitlin and Elder 177). Agency becomes both the “ability” to act and confront problems as well as the perceived capacity in one’s ability to act: “self-perceptions of agentic capacity have social consequences. People who perceive more agency are more likely to persevere in the face of problems, either within situations or in encountering obstacles that represent structural impediments” (Hitlin and Elder 182). This is how solidarity expressed in the texts of Habashi and Mandela operates. The texts illustrate “free” subjects empowered by their belief in their capacity to “act” and hence resist the hegemonic strategies of state power and the institution of Apartheid.

Referring to one of the early incidents of imprisonment against charges of joining a campaign of defiance against the petty laws imposed by the government in June 1952, Mandela voices this spirit exactly: “Marshall Square [police station prison] was squalid, dark, and dingy, but we were all together and so impassioned and spirited I barely noticed my surroundings. The camaraderie of our fellow defiers made the two days pass quickly” (115). This sentiment was invoked again in 1956 when, together with 156 other ANC members (almost the entire executive leadership of the ANC), Mandela was detained in Johannesburg prison, known as the Fort. Despite everything, the men could overcome the enormity of the pain empowered by the presence of comrades: “Our communal cell became a kind of convention for far-flung freedom fighters. . . . Now our enemy had gathered us all together under one roof for what became the largest and longest unbanned meeting of the Congress Alliance in years” (175). Mandela explains so expressively the importance of such acts of solidarity and commitment. In Robben Island, as much as he is aware of his leadership powers, he is conscious of the significance of the role played by other comrades: “It would be very hard if not impossible for one man alone to resist. I do not know that I could have done it had I been alone. But the authorities’ greatest mistake was keeping us together, for together our determination was reinforced” (341).

Habashi, on the other hand, speaks about the necessity of col-lective resistance, even if over small matters such as improving food or better living conditions. Reflecting on the protest and the sabotage of the wagon that carried food to prison, on grounds of objecting to the bad quality of the food served, Habashi speaks painfully about the little victories achieved regarding demands:

That night we dined content with our feelings of relief and accomplishment. I climbed into my bed on this night and lay awake mulling over how people’s dreams and struggles diminish once they are imprisoned – they become relatively petty dreams and struggles. For example: reclaiming the right to enjoy a proper meal, demanding basic sanitary norms – and receiving soap or washing detergent in return, or wining the freedom to smoke cigarettes. Inmates may feel embittered because they have to undertake such struggles for the realization of their basic needs in prison. However, it is always in their interests to engage in these struggles, to persist in their efforts, and to never lose sight of their demands – for these are decisive struggles, the outcomes of which shall naturally influence these inmates’ sense of self-worth. Therefore, inmates should always strive to win these small victories. (46)

Habashi questions the limitations imprisonment imposes on prisoners’ ambitions and the transition experienced from struggling for a cause to protesting in order to achieve small and even petty demands. However, he highlights a key psychological factor in this equation of injustice, namely, keeping the spirit that together they are capable of having their say despite all attempts of suppression. It is an important exercise of resistance that helps human beings preserve their self-esteem, strongly needed, should they wish to pursue the struggle when released. Mandela and Habashi could understand that the intent of the dominant power is to demolish opposition and break their resolve. They realized that collective resistance is indispensable to keeping the struggle alive.

The acts of asserting “capacity” to extend the limits of prison and to resist oppression took various forms:

Opposition employed by prisoners to ensure physical and mental survival invariably developed into a second and more far-reaching level of resistance, that intended to respond to the negative psychological effects of imprisonment. On Robben Island, to resist the state’s attempt to destroy them mentally, the Islanders began (and later extended) a cultural, academic, and sporting life within the prison. (Buntman and Huang 50)

Indeed, one of the primary tactics adopted collectively to defy the deliberate repression in prison was to organize cultural and recreational activities. In the opening chapter of the part titled “Robben Island: Beginning to Hope,” Mandela describes the various cultural and recreational activities organized by the prisoners ranging from Christmas concerts (where warders were “the audience’’ enjoying themselves as much as the prisoners) to chess and draught tournaments, to organizing a “drama society” that offered performances at Christmas (395-97).

Habashi echoes similar cultural and recreational accomplishments in the aftermath of the serious crackdown on political prisoners on par with that experienced by Mandela and his colleagues on Robben Island.

He records the qualitative shift in the treatment of political prisoners in 1961 when the authorities realized that their notorious behavior could not have continued unquestioned. The degree of “freedom” granted transformed the inmates psychologically from feeling that they are ‘prisoners” to feeling like “exiles.” In El-Kharga Prison, this corner of “hell on earth,” there emerged the cultural renaissance of El-Wahat” (181). Over more than ten pages (181 -93), Habashi provides a detailed account of the cultural activities conducted in this prison indicating the names of the inmates involved in the process: “This renaissance was the product of barefooted, half-naked, and half-starved inmates. In this place of isolation, we sought to replace the culture of oppression with the culture of arts, creativity and greenery. Our cultural experiment in El-Wahat resembled a rose that had sprouted in the heart of hell” (181). His account of this cultural renaissance includes the composition of very famous pieces of literature, the unleashing of the creativity of others in terms of acting, and above all the construction of a Roman style theater (using handmade bricks) where all the plays and performances were made (189-92).

Once again, defiance through culture is cited by Habashi who never failed to employ his skills as an engineer in all the projects he undertook in prison. During his term of imprisonment in Abu Za‘bal Prison in 1974, on charges of attempting to re-establish the Egyptian Communist Party, Habashi was driven by the urge to “do something productive” and to “beautify” the prison (224). Thus, he decided to build a fountain surrounded by a number of small statues each symbolizing one form of oppression in prison: lost beauty, crushed joy, and thwarted revolution. Despite the fact that Habashi spent only six months in prison, he managed it) complete this work of art that stood as an artistic symbol of the triumph of the oppressed.

Another powerful tactic of solidarity was education. Robben Island was dubbed the “University.” Mandela explains that the learn-ing skills of all were honed:

In the struggle, Robben Island was known as the University. This is not only because of what we learned from books, or because prisoners studied English, Afrikaans, art, geography, and mathematics, or because many of our men . . . earned multiple degrees. Robben Island was known as the University because of what we learned from each other. We became our own faculty, with our own professors, our curriculum, our own courses. We made a distinction between academic studies, which were official, and political studies, which were not. (406-07)

Mandela states that this endeavor was partly driven by necessity, as it was believed that the young men admitted needed this kind of education to be able to make informed decisions and learn about the ANC, the focus of this large solidarity movement that brought them to prison in the first place. Thus, “(political prisoners on Robben Island both strengthened the skills and capacities of existing leaders and were able to nurture previously untrained supporters” (Buntman and Huang 58).

Educational activities in the case of Habashi may not have been as structured as those on Robben Island. Nonetheless, they are represented as an important means of support, while being necessary for survival, as they simulated the normal life political prisoners craved. During Habashi’s imprisonment in El-Taur Camp in the 1940s, university professors decided to exercise their profession in prison and teach the illiterate. Thus, they

added a great deal of flavor to an otherwise relatively bland existence…. Eventually small “schools” sprang up amongst the inmates—in order to educate the less fortunate inmates. The illiterate inmates amongst us were taught to read and write, while other “schools” featured lectures covering a wide variety of subjects—especially scientific and cultural subjects. (73-74)

Inasmuch as these and other activities were relevant and productive, they seem to have been part of the greater desire of the inmates to overcome this trauma of incarceration and rather try to reclaim the normal life each one of them led outside. Studying was once again one of the instruments collectively employed by Habashi and his comrades in El- ‘Azzab Prison – where he was confined in Prison Chamber No. 4 with around fifty other inmates: “In our prison chamber we would try to make use of our time by conducting cultural and educational activities – such as discussion groups, book review sessions, and study groups for the literary analysis of plays or novels – as this was the only means of ‘productive’ entertainment available to us” (154).

Attending to intellectual needs while using educational and cultural activities as a venue for expressing resistance to the attempts of repression exercised by the state power is not the sole domain of solidarity and resistance. Indeed, food and its consumption are also an arena for the struggle over power and the maintenance of identity. Among the key tactics employed was the use of hunger strikes, which seems to be one of the timeless approaches resorted to. As Mandela puts it eloquently: “A hunger strike consists of one thing: not eating” (368). However, for this approach to bear any fruit, it had to be a collective action. Mandela relates one of the successful strikes on Robben Island in 1966, when the political prisoners learned that others in the general section were striking. Thus, political prisoners followed suit without knowing the exact reason for doing so. This act of solidarity was based on supporting “any strike of prisoners for whatever reason they were striking” (369). The justification of this attitude is also succinctly phrased by Mandela to the authorities when asked about the reason that made political prisoners join as well: “men in F and G were our brothers and our struggle was indivisible” (369). That was Mandela’s announced stand, despite his own personal doubts concerning the worth of starving oneself and giving the authorities a reason to rejoice at the suffering of prisoners. Nonetheless, the position he took was expressive of his utter support for the group: “once the decision was taken … I would support it wholeheartedly as any of its advocates” (369). Solidarity with the group or cause is an indispensable device for fending off the subjugation exercised by the authorities.

Likewise, Habashi had his own doubts about the worth of hunger strikes. Many a time does Habashi put the narrative to a halt and wonder about the “worth” of the small acts of defiance undertaken in prison together with his other colleagues. It is as if he does not want to lose sight of the bigger picture, namely, the national struggle that is happening in reality outside. He always juxtaposes this larger fight against injustice with the action in prison:

Of what value was our hunger strike which lasted a few days – in context of the greater picture of events in the year 1948? Does this hunger strike have any intrinsic value worth documentation, or even worth mentioning? In my assessment, every moment that a human being spends in the course of reclaiming his or her natural rights is a moment of dignity and self-respect, and thus it is a moment or effort worth being documented. (60)

Thus. Habashi acknowledges the importance of such acts of solidarity that might seem futile or onerous. As much as Mandela, he believes that even if they boiled down to being representative of defiance only, they are necessary for confirming the human dignity of the oppressed.

In addition to the use of hunger strikes as a means of self-assertion and resistance, food and its consumption are also exploited by the authorities to express power and domination: “Eating is a recurring and necessary part of survival that becomes a key element of the regular prison routine. Furthermore, because of the symbolic power that food possesses, it is a form of communication through which expressions of domination and resistance can be made’* (Godderis 256). Indeed, food is used as a tool by the authorities to break resistance and control inmates, to express leniency, or even to demonstrate discrimination. In Robben Island, “diet is discriminatory” as Indians and people of color “received a slightly bet¬ter diet than Africans” (Mandela 342). Violation of the prison code entailed “either solitary confinement or loss of meals” (343). Deprivation of specific food staples such as milk (Habashi 63) or a refined form of bread is also a regular form of punishment. Apart from hunger strikes, the ability to share food or to provide for exceptions on special occasions is another conscious act of defying the scarcity and poor quality of food served in prison. On birthdays, “we would pool our food and present an extra slice of bread or cup of coffee to the birthday honoree” (Mandela 414). Moreover, both Mandela and Habashi provide lengthy accounts of the times when prison authorities had succumbed to the demands of improving conditions in prison, particularly through permitting cultivation of food crops. This gesture is described in detail by Habashi when the Prison Commander granted El-Wahat prisoners a plot of reclaimed desert land, on which prisoners were able “to grow a number of vegetables and legumes including—okra, a variety of beans and other plants” (175). During the years Mandela spent in Pollsmoor Prison, in preparation for his release, one of the signs of the recognition of Mandela by the state was the tremendous improvement of his diet (448) and the permission as well as the facilities provided for him to grow food crops and to share these crops with the warders and prison kitchen (449-50).

In addition to the positive spirit and forward looking attitude that both Mandela and Habashi managed to preserve throughout their journey by the support of friends and the reassurance provided by being surrounded with like-minded comrades, regional and international solidarity played a key role in boosting their morale and at times even effecting changes in the dire reality they experienced – even if limited. In this sense, solidarity traversed the limits of geography. Along these lines. Habashi recounts the incident of the killing of the communist activist Shouhdi ‘Attiya El-Shafe’i, as it served as a landmark in the treatment of (communist/socialist) political prisoners in Egypt. Shouhdi was a defendant in a legal case and had stood military trial, and the authorities were unable to deny having him in their possession. Nasser learned of his murder while he was in Brijuni (former Yugoslavia) in the company of Premier Josip Tito attending a parliamentary session. Upon hearing the news of his death, the MPs stood for a minute of silence to commemorate ‘Attiya’s death. At this moment, Nasser—according to Habashi — realized that his commitment to socialist policies could be at stake. Thus, orders were issued to prohibit torture in prisons. This included El-Wahat Prison. The instructions were even communicated to the inmates.

The new rights included “the right to correspondence with family members and access to the canteen, amongst other freedoms” (179) Habashi, however, reads the incident from the perspective of appreciation of this act ot sacrifice by their comrade: “In dying, Shouhdi had sacrificed his life and soul for the sake of his comrades, fellow inmates, and for the sake of all political prisoners in Egypt” (179). This incident testifies to the intricate workings of solidarity, which is not simply about subscribing to a cause. In fact, solidarity becomes an act and a position taken with the hope of creating more space for dignified existence.

Likewise, Mandela’s imprisonment together with other defendants during the Rivonia Trials (1963-1964) stirred much denunciation among left politics proponents. Mandela himself attests to this solidarity:

The world had been paying attention to the Rivonia Trial. Night-long vigils were held for us at St. Paul’s Cathedral in London. The students of London University elected me president of their Students’ Union, in absentia. A group of experts at the UN urged a national convention tor South Africa that would lead to a truly representative parliament, and recommended an amnesty for all opponents of apartheid the UN Security Council . . . urged the South African government to end the trial and grant amnesty to the defendants. (325)

This is of course far from being an exhaustive examination of international solidarity. But these incidents related by Habashi and Mandela themselves attest to the power of solidarity in enhancing the lives of political prisoners. Moreover, all such support testifies to the multiple forms of solidarity indicated by David Featherstone, who argues that solidarity is not a given identity to which supporters subscribe, but is rather a dynamic state that crosses borders, where “solidarities” in support of one cause exist to challenge other counter-solidarities in turn (23).8

Conclusion

The personal narratives of Mandela and Habashi emphasize human agency and the potential for self-transformation and social change by retelling a story that is touching, while embedded in concrete experience. As typical autobiographical narrators, Mandela and Habashi “place themselves at the center of the stories they assemble and are interested in the meaning of larger forces, or conditions, or events of their own stories” (Smith and Watson 14). At the same time, both texts truly belong to the genre of prison writing. Through writing they challenge the

isolating power of the prison, in an effort that is at once per¬sonal and political: to recover agency through a willed, virtual relocation of the prison writer himself . . . and from this space to publicly reconnect the prison cell, and the suffering that occurs there. . to the apparatuses of power that turn to prisons as a primary means of establishing order. (Larson 145)

However, the question remains: Is there a difference between the experience of trauma where the individual falls victim to the arbitrary actions of brutal power—while being entirely helpless and not ideologized—and that of being traumatized for a political cause, which in a sense is expected? Both Habashi and Mandela were aware of the ugly consequences of their defiance of oppressive authorities, yet they still decided to pursue the path of the struggle, as stated clearly by Mandela. He and his comrades were “accepting responsibility for actions [they] had taken with pride and predetermination” (322). They willingly walked this thorny path of struggle. Nevertheless, as both mention directly and indirectly time and again, they would not have been able to do so without the support of friends.

This article has argued that the power of friendship and support could help counterbalance the tremendous pain, both physical and psychological, imposed in the case of oppression – political and otherwise. At the same time, the moral commitment on the part of the person on whom power is exercised – who in this case happens to be an opponent of injustice or a freedom fighter—helps imbue the personal experience of suffering with purpose. Thus, solidarity and friendship become the main drive of endurance for a person in times of hardship, and at the same time a commitment towards the larger group/community to be preserved. In fact, commitment to friendship in the wide sense of the word contributes to the desire to ensure the harmonious diversity of society.

In the case of Mandela, it is even taken a step further: it leads to his involvement in the long process of reconciliation and forgiveness in the South African society, ultimately commissioning the establishment of the Truth and Reconciliation Committee. The political endeavor involved consisted in

freeing the community from the crushing weight of an awful history and give it a chance to restore a relationship with another community that it has harmed or by which it has been harmed. Indeed, it would allow a relationship of trust, peace and concord between communities previously at odds with each other to be restored. (Vandevelde 264)

In the case of Mandela, this engagement in the process of transformation was not an easy decision, but he was able, with the support of his comrades along the path of freedom, to help forge an alternative potential future. Habashi’s powerful positive spirit, augmented by the love and support of his close circle of friends and acquaintances, might not have resonated as widely as Mandela’s, given the limited influence of the Communist Party and the appeal of communism to Egyptians. However, within the circle of communists, Habashi remains an icon of resilience inspiring integrity and perseverance for undoing injustice to many.

Notes

1 It is true that Mandela’s autobiography was first published in 1994 with the

support of Richard Stengel. However, the core part of the text was written clandestinely between 1975 and 1976 during imprisonment on Robben Island, with the help and encouragement of his life-long triends and comrades Ahmad Kathrada and Walter Sisulu (Mandela 414-18).

2 Mandela and Winnie got divorced shortly after his release from prison in April 1992 (Mandela 522). However, this separation does not negate the support they offered one another during the difficult years of the struggle.

- For an anthology of extracts of key works of the philosophical tradition’s engagement with friendship from antiquity until the twentieth century, see Pakuluk’s anthology of seminal treatises on friendship from Aristotle to Tclfer.

- Aristotle discusses friendship in two books in this treatise and elsewhere in his writings on politics. His fundamental assumption is that friendship is “virtue or implies virtue” (n. pag.) and that the existence of friendship as such entails justice.

5 This is the Arabic acronym for the Democratic Movement for National Liberation. There were different fraction in the communist movement in Egypt and HADITU was the most prominent in the 1940s.

- Reference here is to a proverb used by Winnie’s father during the speech he gave

at her wedding reception: “If your man is a wizard, you must become a witch!” (188), i.e. she has to follow her husband and support him in his endeavors.