Reporters, photojournalists, lawyers and academics commenting on the hunger strike of convicted terrorist Dimitris Koufodinas found their Facebook accounts suspended by the platform. Facebook admitted “mistakes” but failed to provide a full explanation conceding rather magnanimously: “We do allow people to neutrally discuss”.

By

Mar.8, 2021

In the past week, Facebook suspended a number of Greek user accounts which had been posting about Dimitris Koufodinas. Koufodinas is serving 11 life sentences for crimes related to domestic terrorism in Greece, including 11 murders, perpetrated as a member of the 17 November terror group.

17 November were active between 1975 and 2002, during which time their victims included Greeks and foreigners, including former torturers from the time of Greece’s military dictatorship, businessmen, publishers, journalists (including the brother-in-law of current Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis), judges, police officers, officials and ordinary staff of the US,UK and Turkish embassies in Athens (including a CIA station chief), and in one instance a bystander, student Thanos Axarlian. The perpetrators were arrested in 2002 and put on trial. Several 17N members, including Koufodinas, are still serving long prison sentences.

Koufodinas has been on hunger strike since January 8, protesting his move to maximum security prison outside Athens. His protest has caused a clear rift between the conservative government, which refuses to make any concessions on the move, and left-leaning parties of the opposition, calling for an intervention to prevent his death. On March 5 Koufodinas suffered from kidney failure, his doctor claiming “his life is in imminent danger”.

Fierce debates have also been taking place in judicial and academic circles as well as on social media over the legality of the government’s actions and the legitimacy of his defence team’s claims. An MEP from Spain filed a question in the European Parliament. Meanwhile, public protests numbering in the hundreds have been taking place daily in Athens and other Greek cities calling on the government to change its stance, while a series of attacks on police and property have been linked to more extreme support for his cause.

The Greek police is said to fear a surge in rioting as the confrontation worsens, while there is more widespread concern over the social and political tensions that the case is stirring up, coinciding with the economic uncertainty created by the ongoing pandemic.

In the midst of this potentially explosive situation, it emerged this week that several Facebook users in Greece had their accounts temporarily suspended after posting about the Koufodinas case.

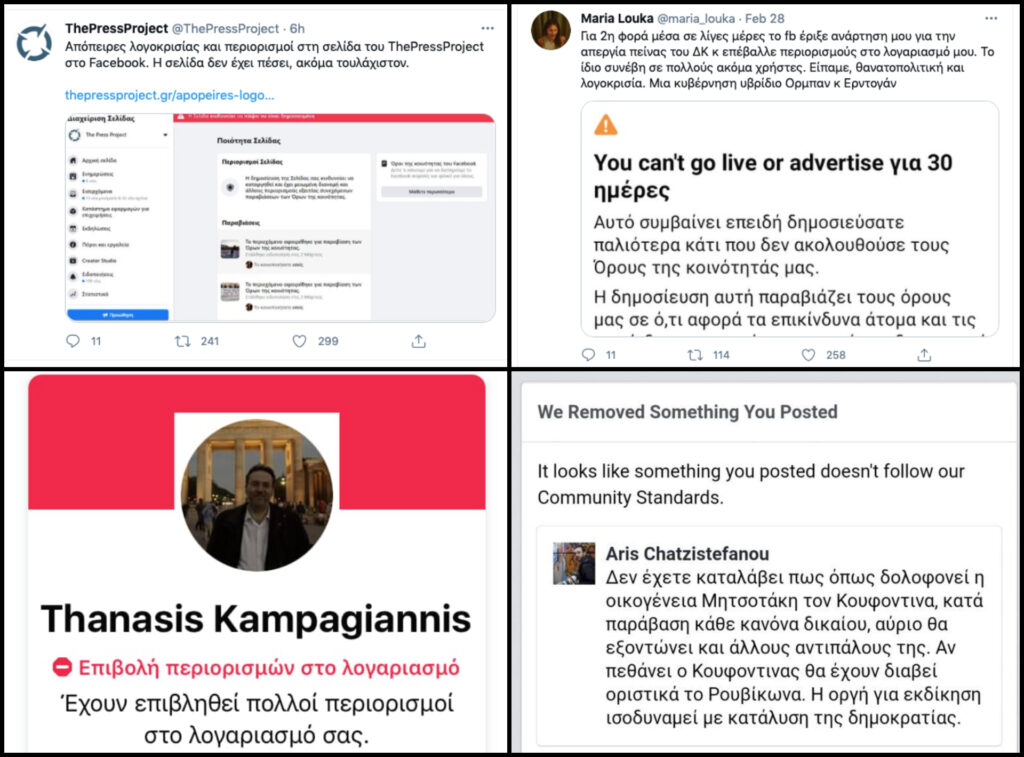

The suspended accounts included a media outlet hosting a debate with invited lawyers on the case (ThePressProject), several journalists (including Aris Chatzistefanou and Maria Louka) and photojournalists (e.g. Marios Lolos, Tatiana Bolari, Lefteris Partsalis) who had posted photos of the protests, a lawyer famous for representing the victims of neonazis in the Golden Dawn Trial (Thanassis Kambayiannis), an academic (Natassa Tsoukala). While some were voicing support for Koufodinas, others were simply reporting on events or engaging in debate about the prisoner’s legal rights and whether the government was following the “rule of law” as it claimed. Some notable examples of account suspensions can be found in a Twitter thread compiled by journalist Yiannis Baboulias.

A statement issued by the Greek Photojournalists’ Union highlighted the issue at stake:

“Photojournalists’ duty is to run in where others run away, to record events and show the images to the world ‘so that no-one can say “I didn’t know”’.

Today the Facebook profiles of several colleagues have been taken down for doing just that. Publishing images of protest on the subject of hunger striker Dimitris Koufodinas.

We don’t know how Facebook wishes to describe this, but we call it censorship.”

Some reacted by accusing the government of censoring its critics through social media, comparing it to authoritarian figures such as Hungary’s Orban and Turkey’s Ergodan.

Others pointed the finger at Facebook’s outsourced moderators, thought to include Teleperformance, one of the largest global call-centre companies with a large presence in Greece which Reporters United has previously investigated. During the first wave of the pandemic, Teleperformance provided free call centre services to Greece’s National Public Health Organisation (EODY), the domestic equivalent of the CDC.

A third accusation which emerged was that a mass reporting campaign orchestrated by government supporters had resulted in the suspensions

Facebook’s response: “We do allow people to neutrally discuss”

Reporters United and other organisations contacted Facebook with questions relating to its actions. We received a brief statement from a Facebook spokesperson in English via the company’s PR representatives in Greece, Hill+Knowlton Strategies.

“Terrorists, violent extremist groups and hate organizations have no place on Facebook and Instagram. Under our Dangerous Organizations and Individuals policy we ban members of terrorist organizations like Mr Koufontina from using our platforms and also remove posts that praise or support these individuals whenever we become aware of them. However, we do allow people to neutrally discuss these individuals and share news reports about their actions. While our systems are making a lot of progress, they are not perfect and sometimes we make mistakes, as happened here in a few instances. We’ve restored content that was taken down in error when made aware of it ”

A lengthier explanation was distributed to the Greek media, but only made available in Greek.

The statement contains several interesting points.

Firstly, Facebook admits that it made “mistakes” in applying its policy in several instances of posts referring to Koufodinas’s hunger strike and the reactions to it.

Facebook’s representative claims that the suspensions were carried out in accordance with the platform’s policy on Dangerous Individuals and Organisations. However, the statement acknowledges that Facebook also removed posts which “neutrally discussed” or reported on the protests surrounding Koufodinas’s hunger strike.

Facebook also provided Reporters United with further background information. In it, Facebook states that the accounts were identified through a combination of user reports, AI technology and human moderators.

Facebook denies that it takes action based on mass user reporting. In its response to the Greek media, Facebook stresses that:

“We do not take action against a piece of content based on mass user reporting. Even a single report is enough for us to remove a piece of content if we confirmed it was violating” (The statement is underlined in the Greek original).

Unanswered questions

Facebook’s response through its representative leaves key aspects of the incident are not explained.

For example, the suspensions did not appear to be random, and neither were they comprehensive. Several key accounts, including that of Koufodinas’s son who regularly expresses unmitigated support for his father, were not suspended, while accredited journalists and established media outlets were hit by the ban.

Reporters United asked Facebook whether it had been contacted by the Greek government in relation to the suspensions, or if the government had reported any content to the platform as inappropriate or abusive, but the company did not provide a response.

We also asked the company whether their Greek-language content moderation is provided by Teleperformance. We did not receive a response to this question either.

Facebook informed us only that they use 15,000 content moderators, and that Greek is one of 50 languages spoken.

The company is notoriously secretive about its moderating process, only publishing its community standards in 2018 after they were leaked to the press. They are, however, known to outsource the work to third-party companies. In 2019, the Greek investigative website insidestory.gr published interviews with Greek-language moderators for Facebook who had been employed by Arvato, a subsidiary of the Bertelsmann group based in Berlin. According to the former contractors, the Greek-language team in Berlin ranged between 25-60 members who worked for minimum wage reviewing up to 2,000 content reports per day, while the only requirement for the job was fluent Greek.

This by itself raises questions about the quality and independence of decision-making in Facebook’s content moderation process.

Whatever the mechanics of this episode, Facebook’s actions had the effect of stifling information-sharing and debate on a topic of public interest in a manner which appears to suggest political bias – even if the intent was not there.

This is a massive failure for Facebook’s content moderation, an activity for which the platform is already coming under increasing scrutiny by governments and rights advocates worldwide. The fact that Greece is a small market for the social media platform, and that the posts concerned an issue of mostly domestic interest, may account for the carelessness with which the issue was treated.

Facebook, however, is the most popular social platform for news in Greece, where social media are a more trusted news source than print or TV, according to the Reuters Digital News Report 2020.

Taken at face value, Facebook’s own explanation suggests that the platform cannot be trusted to moderate its user content on issues with any nuance or sensitivity. For example, is it reasonable to put a journalistic photo of a banner with slogan on the same footing as a user’s post with the same slogan?

The incident also raises larger questions of much broader significance. For instance, should a private company with such a dominant market position – or its sub-contractors – have the discretion to effectively silence the press in a democracy?

Given the platform’s well-documented power to shape perceptions and real-life events, this should be a subject of concern for everyone, not just Facebook users and Greek citizens.

Published at www.reportersunited.gr