by

Posted December 23, 2016

The attribution of extreme events to human-induced climate change—what is termed anthropogenic climate change—has been a burgeoning scientific frontier as scientists grapple to understand how our activities are altering the earth system. This past week at the annual meeting of the American Geophysical Union, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association (NOAA) and the American Meteorological Society (AMS) announced the release of the most recent in a series of annual, special editions of the Bulletin of the American Metrological Society (BAMS), “Explaining Extreme Events From A Climate Perspective 2015”

The report focuses on 26 peer-reviewed research papers from 116 scientists in 18 counties that highlight extreme weather events across five continents and two oceans from 2015. Using combinations of historical data, trend analysis, and models, this collection of papers seek to determine how each event was influenced by human-induced climate change. Events in the report include extreme high temperatures and heat waves in Western and Northwest China, Central Europe, Egypt, Japan, Indonesia and Southern Australia, along with an assessment of US daily rainfall extremes, the Alaska Fire Season, extreme drought in Canada and Indonesia, and heavy rain in India.

The prevailing narrative in this year’s report is the influence that climate change is having on extreme heat and drought events.

“Without exception, all the heat-related events studied in this year’s report were found to have been made more intense or likely due to human-induced climate change, and this was discernible even for those events strongly influenced by the 2015 El Niño.” — from Explaining Extreme Events From A Climate Perspective 2015

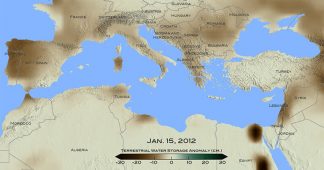

2015 is currently the warmest year on record, with a 0.90 degree Celsius (or 1.62 degree Fahrenheit) deviation from the 20th century average. In this year’s report, there is a summary of global surface temperature from Dr. Jonghun Kam and colleagues that is notable for a couple of reasons, foremost for using only areas of the globe where 100 years or more of observational data are present, which provides an incredibly high degree of confidence in temperature trends for those areas.

Kam and peers find that nearly 30% of the global surface area included in this large data set experienced either a first, second, or third warmest summer on record in 2015. It should be noted that many areas of the globe, including southwest California and much of the Pacific and Indian Ocean where we know accelerated warming is occurring, was not included as observational records did not meet the 100 year threshold.

“The dog was barking in the night, but we did not have the data to hear what the dog was saying” – Dr. Martin Hoerling

The term El Niño arose in the scientific literature in the early eighties, and since then, as Dr. Jeff Rosenfeld noted Tuesday, has been blamed for everything from civil wars in Africa to the fall of the Incan empire. The current state of the science however, has allowed research to disentangle the effects of 2015’s strong El Niño with additional forcings attributable to climate change.

In 2015, three separate events each resulted in over a $1 billion dollars (US) in damages in the contiguous US: the late May floods in Texas, Hurricane Joaquin in October that resulted in catastrophic flooding in South Carolina, and the unseasonably heavy December rains in the Mississippi basin. In an analysis of US rainfall extremes, Dr. Klaus Wolter and colleagues note that the contiguous US has experienced significant upward trends in heavy precipitation over the last century. Wolter and peers attribute extreme events of 2015 and the overall upward trend in-part to human-induced climate change as the spatial pattern of events relates well to overall increases in global temperatures. Of the 10 years with the most extensive extreme daily rainfall events, 9 have occurred since 1990.

Attribution of extreme events to human-induced climate change can be difficult in a logistical sense in that often the scientists who are concerned with understanding the causes of any extreme event are not the same concerned with calculating the magnitude of the event.

Attribution of extreme events feedback to the science. There are really two questions:

1) What are the long-term contributions that climate change will have to event frequency—how much more often will an event occur in a warmer world?

2) What are the long-term contributions of climate change to event intensity—how much more severe will any given event be?

Whenever there is any severe weather event, there is often an insatiable desire for “real time” analysis and attribution. Is this event directly related to human climate change? But as this report notes, the conversation is subtly shifting from “how did this event happen?” to also including “how well was this event anticipated?”

There is no uniform method of event attribution. Every event must be examined independently. There are “three pillars” of event attribution:

1) The quality of the observational record. Is the data sufficient to test the hypotheses generated? How long is the record? How spatially representative is it?

2) The ability of models to simulate that event. Are our current computer models and simulations adequate enough to be able to represent and simulate the event we are interested in?

3) Our understanding of the physical processes that drive the event and how they are being impacted by climate change.

Future use of attribution science depends on the parties of interest, as Dr. Stephaine Herring and her co-authors note, insurance agencies may value the “robustness” of analysis in order to best assess damages, while aid agencies may value “swiftness” so they can rapidly mobilize to an area to offer support.

A recent paper in Environmental Research Letters from Dr. Daniel Mitchell and colleagues is the first time that attribution scientists teamed up with public health officials to look at how mortality was impacted by a specific event—the 2003 European heat wave. Their findings were startling, with about 20% of the summer deaths in London and nearly 70% of the summer deaths in Paris attributable to human-caused climate change.

This report highlights not only how our environment, climate and weather are changing but also how scientists, citizens, and policymakers must adjust moving forward. Disentangling the effects of climate change from seasonality or climate variability can be difficult, but it is a challenge necessary in our changing world. Adaptation science offers a means for better adaptive measures and decisions. Scientists will continue to pursue the questions of how the magnitude and frequency of extreme weather events are being altered by climate change. In the five years that NOAA, AMS and BAMS have been compiling this report, 104 different studies have been included. The majority of the scientific papers considered have covered heat, drought, and precipitation events. Of the 29 papers on heat, only 1 failed to attribute the event to climate change. But of the 24 studies include on precipitation, 62% did not find human influences contributed to the events. Studies on drought result in an equal split. A lack of attribution of any event directly to human causes is not necessarily a not guilty verdict, but often perhaps an inability to meet one of the pillars of attribution. As our understanding and abilities in attribution increase, there is hope we can better find the sources and drivers of extreme events and better understand the effects of how our actions are influencing climate and weather in a very tangible and real way.

However, there is a concern in the simple binary attribution of a “yes” or “no” to human-induced climate change. Dr. Friederike Otto, Oxford University, noted that the São Paolo drought from 2015 was severe and significant, but was only a 1 in 10 year event. Statistically, this means São Paolo has an approximately 10% chance of experiencing a drought of this magnitude in any given year. However, other factors influenced by climate change have decreased the resiliency of systems—environmental, societal, political, etc.—to handle events even of this magnitude. There is a cumulative effect. A body that is already plagued by a persistent, chronic condition will not be able to handle even a common cold as well as a healthy, functioning body. If we are to make better, more adaptive decisions ahead of extreme events, this is something else we need to consider.