The negotiations over a European Union bailout were riven with splits on whether “frugal” Northern states should have to assist their coronavirus-hit Southern partners. But while the eventual €750 billion deal was widely hailed as a victory for European solidarity, its details show that it will aggravate the EU’s inequalities even further.

By Peter Wahl, Klaus Dräger

Sep. 6, 2020

Too many interests of German capitalism and its government would have been at stake if the conflict between North and South had been allowed to escalate any further. Yet the summit did not come out with a message of “Joint liability for debts” among the member states. Rather, the EU’s Recovery Program (Next Generation EU, in EU speak) is just an exceptional firefighting effort designed to contain the crisis for the next three years.

Among the supporters of “More Europe,” the program led to euphoric reactions. After ten years of permanent crises, they now believe in a historic breakthrough — a kind of “Hamilton moment” for Europe. EU Council president Charles Michel boasted, that this was now the EU’s ”Copernican turning point.” And Thierry Breton, a French heavyweight in the European Commission, responsible for the internal market, services, military, and space affairs, bragged that “in the last one hundred days the EU had moved forward more than in the thirty years before.”

However, all this hype hides three painful truths. The economic impact of the recovery program is grossly overestimated; the conflicts over money are based on deeper, structural shifts in the EU’s informal architecture of power; and the differences of principle about the further development of the EU and its final goal, already smoldering for some time, have now come out into the open.

Looking Back

So far, there have been three phases of the EU‘s response to the coronavirus pandemic.

The first phase (February to March) was very chaotic — each member state took its own national-level actions, there was no coordination at the EU level, and no solidarity for the most affected countries, such as Spain and Italy, at the time. As a result of this chaos, in the second phase there emerged a discussion about joint EU coronabonds — to no avail.

Finally, in April the EU Council agreed on its first corona package. €560 billion from the EU level was to be provided to the member states most hit by the crisis, in the form of loans: €240 billion from the European Stability Mechanism (ESM), and €200 billion from the European Investment Bank for small and medium-sized enterprises in trouble. Added to that was the much-heralded €100 billion temporary loan program SURE, to assist member states on short-time work schemes. However — announced in April 2020 — the Commission expects this scheme only to become operational this month. So far, the EU’s first corona package has been quite a non-starter.

The third phase of the EU’s pandemic policy was launched with the joint initiative by Merkel and Emmanuel Macron on the Recovery Program, the European Commission’s subsequent proposals, and the agreements around these principles at the “historic” summit in July. But let’s take a look at where the money is going.

The Regular EU Budget: On Course With Austerity

The €1.8 trillion pledged to ”save Europe” sounds like an ambitious promise. But €1.074 trillion of this is the normal EU budget framework for 2021 to 2027, representing 1.1 percent per year of the EU’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) as of 2019. And this seven-year budget is based on austerity. Compared with the previous budget for 2014–2020, the funds for agricultural policy have been cut by €46 billion (but still remain the biggest item). There is also a 10 percent reduction for cohesion policy. Significantly less goes to the European Social Fund, the Erasmus program (education and training), for research, or for combating child poverty.

In contrast to the European Commission’s draft, the additional funds proposed for research (Horizon Europe) in the Next Generation EU package have been cut, as has the “greening” Just Transition Fund. This latter fund’s official aim is to assist member states in phasing out coal and other environmentally damaging industries, in order to move forward toward climate neutrality and to cushion the employment and social effects of the regional restructuring that results.

Commission president Ursula von der Leyen‘s ”EU Green Deal” is clearly battered — indeed, nongovernment organizations (NGOs) such as Corporate Europe Observatory are very critical of the Commission’s conception. An alliance of NGOs led by Climate Action Network (CAN) and Bankwatch looked at the “national energy and climate plans” of many member states, as demanded by the EU with a view to implementing its “Green Deal.” According to these NGOs, too many EU countries still envisage “put[ting] money [into] harmful measures such as development of new fossil gas infrastructure, exploitation of national fossil fuel resources, use of biomass in low-efficiency heating systems and investments in non-renewable energy sources.”

On the other hand, concerning the EU budget, the rebates enforced by Margaret Thatcher should be abolished after Brexit. However, the German one remains at €3.761 billion annually. For the Netherlands, Austria, Sweden, and Denmark, the discounts were even increased in July. Normally, there is a popular narrative in the Northern member states that the EU should not become a “transfer union” in which their taxpayers bail out Southern economies — but here we have a clear case of transfers to the richer countries.

Grants or Loans?

The so-called ”frugal five” (Austria, the Netherlands, Denmark, Sweden, and Finland) were able to record clear successes. €390 billion (instead of the original €500 billion) are to flow to the member states as grants, €360 billion (instead of €250 billion) as loans. With a term of three years, this amounts to €130 billion per year. Measured against the GDP of the whole EU-27 (€14.7 trillion in 2019), this amounts to just 0.8 percent of annual EU GDP. Given the scale of the economic collapse — and as compared to national rescue packages — the much-cited ”bazooka” turns out to be a water pistol.

Loans, on the other hand, are taken up only very hesitantly by member states with high public debt. Even with the first corona package, none of the €240 billion loans of the European Stability Mechanism have been called up so far. Member states fear a stigmatization effect: those who take out ESM loans must expect higher interest rates on their government bonds on the international financial markets.

At the core of the €750 billion “Next Generation EU” package is the Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF). It is to provide €312.5 billion in grants in the three years up to 2024. Member states are to submit annual national recovery plans, which shall be examined by the European Commission and approved by the European Council by qualified majority voting. Countries would receive payments from them, provided they can credibly demonstrate progress towards certain EU targets. These targets have not yet been set concretely. Monies from the reconstruction fund in any case will be subject to the so-called European Semester, the instrument of economic policy governance by the European Commission.

Conditions — A Time Bomb

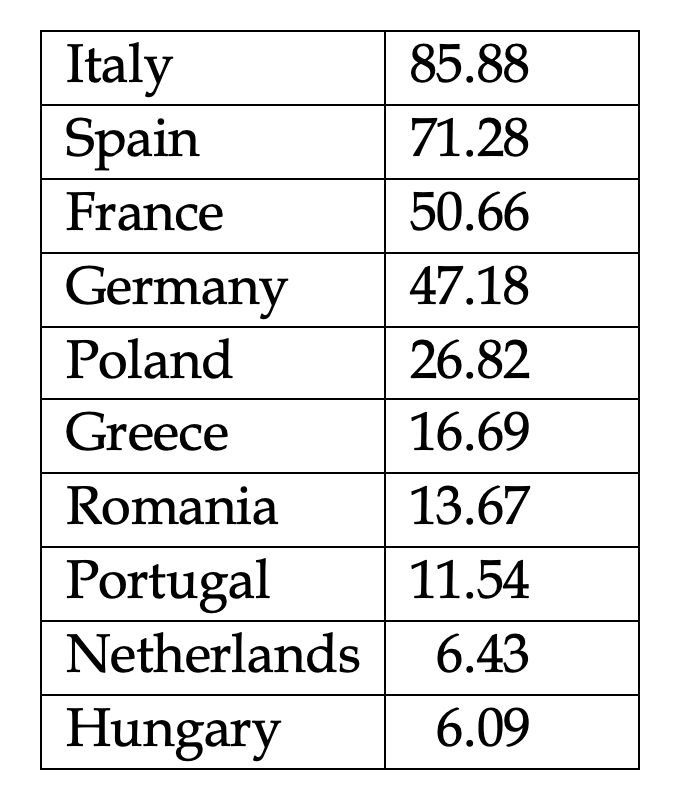

The distribution of the grants from the RRF takes into consideration not only the economic impact of the crisis (with Italy, Spain, and France on top), but may be also some more implicit tactical thinking.

Poland, for instance, is not that badly affected by the crisis, compared to the Mediterranean countries — and nor is Hungary. But against the backdrop of an East-West conflict, concessions to them can be interpreted as the price to pay to neutralize the threat of them vetoing the entire package. They will get less from the cake to be distributed — but still enough for them to accept.

What is also remarkable in this context is the projected amount for Germany. This is due to the revised allocation key for the RRF — favoring big countries and also big “poor” countries. The Netherlands, the leader of the “frugal five,” itself ranks among the top ten beneficiaries.

The ”historic decisions” of the EU summit are extremely meager compared to the challenges concerning public health — not least, facing a second wave — the economic and social effects of the pandemic, and the climate and environmental crisis at large. “Too little, too late,” as many mainstream economists commented. The emergency program might have a slightly dampening effect on the most hard-hit countries. But the dynamics of the economic and social drifting apart of the EU will not be stopped by it.

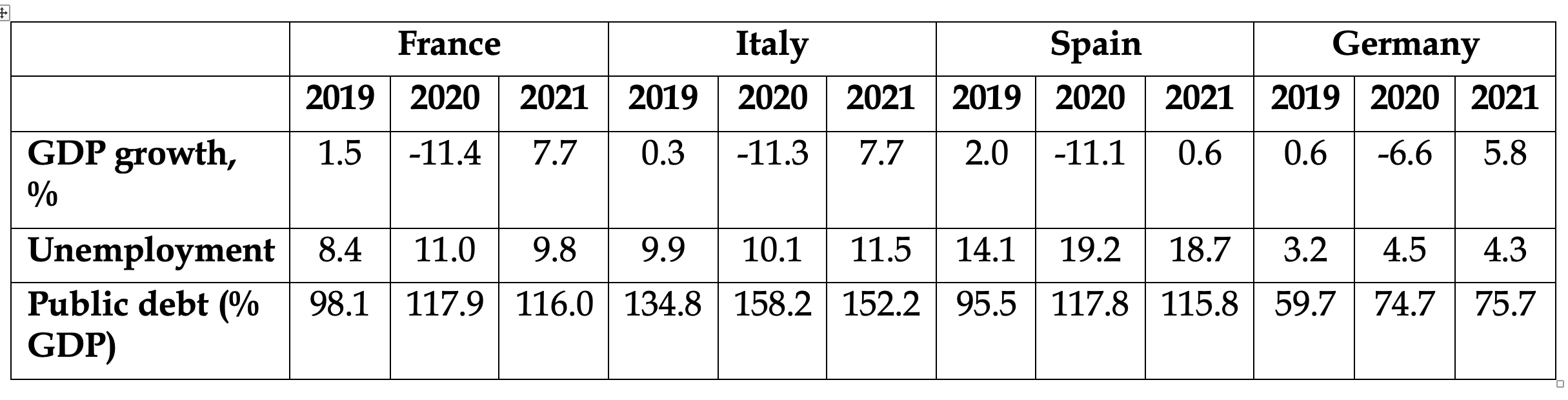

A look at the main drivers of economic fragmentation not only due to the corona crisis shows why (based on OECD forecasts). Firstly, because the economic and social impact of the crisis on member states is very uneven (see table below). While Italy, Spain, and France would be hard hit with a recession of more than 11 percent in 2020, Germany would come off with a less than 7 percent hit. The same discrepancies are expected on unemployment and other indicators.

Moreover, the economic potential of member states to mobilize national resources for emergency measures and rescue packages is also very uneven. By now, the German measures — loans, guarantees, grants, etc. add up to €1.15 trillion, i.e. almost one-third of German GDP. In contrast, France has so far mobilized only €324 billion, i.e. 13.4 percent of its GDP, Italy 17 percent, and Spain only 2.2 percent.

At the same time, the rescue measures are expected to lead to an increase in public debt — in Italy by 24 percent, in Spain by 23 percent, and in France by 20 percent, while Germany might get away with a 15 percent increase. This will further increase the already heavy debt burden of the Southern countries for years to come and restrict their room for maneuver much more than for those with lower debt rates.

* Peter Wahl is one of the founders of Attac Germany and a member of Attac’s Scientific Council. He writes on topics including European policy, development policy, and international relations.

Klaus Dräger was a longtime political adviser for the left-wing group in the European Parliament (GUE/NGL) on employment and social affairs. He is now retired.