By Stephen Frost, Lissa Johnson

Jill Stein, William Frost

on behalf of 117 signatories

February 17, 2020

On Nov 22, 2019, we, a group of more than 60 medical doctors, wrote to the UK Home Secretary to express our serious concerns about the physical and mental health of Julian Assange.1 In our letter,1we documented a history of denial of access to health care and prolonged psychological torture. It requested that Assange be transferred from Belmarsh prison to a university teaching hospital for medical assessment and treatment. Faced with evidence of untreated and ongoing torture, we also raised the question as to Assange’s fitness to participate in US extradition proceedings.

Having received no substantive response from the UK Government, neither to our first letter1nor to our follow-up letter,2we wrote to the Australian Government, requesting that it intervene to protect the health of its citizen.3To date, regrettably, no reply has been forthcoming. Meanwhile, many more doctors from around the world have joined us in our call. Our group currently numbers 117 doctors, representing 18 countries.

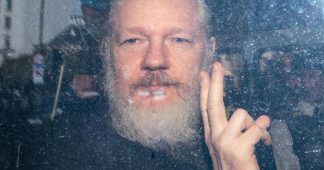

The case of Assange, the founder of Wikileaks, is multifaceted. It relates to law, freedom of speech, freedom of the press, journalism, publishing, and politics. It also, however, clearly relates to medicine and public health. The case highlights several concerning aspects that warrant the medical profession’s close attention and concerted action.

We were prompted to act following the harrowing eyewitness accounts of former UK diplomat Craig Murray and investigative journalist John Pilger, who described Assange’s deteriorated state at a case management hearing on Oct 21, 2019.4, 5Assange had appeared at the hearing pale, underweight, aged and limping, and he had visibly struggled to recall basic information, focus his thoughts, and articulate his words. At the end of the hearing, he “told district judge Vanessa Baraitser that he had not understood what had happened in court”.6

We drafted a letter to the UK Home Secretary, which quickly gathered more than 60 signatures from medical doctors from Australia, Austria, Germany, Italy, Norway, Poland, Sri Lanka, Sweden, the UK, and the USA, concluding: “It is our opinion that Mr Assange requires urgent expert medical assessment of both his physical and psychological state of health. Any medical treatment indicated should be administered in a properly equipped and expertly staffed university teaching hospital (tertiary care). Were such urgent assessment and treatment not to take place, we have real concerns, on the evidence currently available, that Mr Assange could die in prison. The medical situation is thereby urgent. There is no time to lose.”

On May 31, 2019, the UN Special Rapporteur on Torture, Nils Melzer, reported on his May 9, 2019, visit to Assange in Belmarsh, accompanied by two medical experts: “Mr Assange showed all symptoms typical for prolonged exposure to psychological torture, including extreme stress, chronic anxiety and intense psychological trauma.”7On Nov 1, 2019, Melzer warned, “Mr. Assange’s continued exposure to arbitrariness and abuse may soon end up costing his life”.8Examples of the mandated communications from the UN Special Rapporteur on Torture to governments are provided in the appendix.

Such warnings and Assange’s presentation at the October hearing should not perhaps have come as a surprise. Assange had, after all, prior to his detention in Belmarsh prison in conditions amounting to solitary confinement, spent almost 7 years restricted to a few rooms in the Ecuadorian Embassy in London. Here, he had been deprived of fresh air, sunlight, the ability to move and exercise freely, and access to adequate medical care. Indeed, the UN Working Group on Arbitrary Detention had held the confinement to amount to “arbitrary detention of liberty”.9

The UK Government refused to grant Assange safe passage to a hospital, despite requests from doctors who had been able to visit him in the embassy.10There was also a climate of fear surrounding the provision of health care in the Embassy. A medical practitioner who visited Assange at the embassy documented what a colleague of Assange reported: “[T]here had been many difficulties in finding medical practitioners who were willing to examine Mr Assange in the Embassy. The reasons given were uncertainty over whether medical insurance would cover the Equadorian Embassy (a foreign jurisdiction); whether the association with Mr Assange could harm their livelihood or draw unwanted attention to them and their families; and discomfort regarding exposing this association when entering the Embassy. One medical practitioner expressed concern to one of the interviewees after the police took notes of his name and the fact that he was visiting Mr Assange. One medical practitioner wrote that he agreed to produce a medical report only on condition that his name not be made available to the wider public, fearing repercussions.”11

Disturbingly, it seems that this environment of insecurity and intimidation, further compromising the medical care available to Assange, was by design. Assange was the subject of a 24/7 covert surveillance operation inside the embassy, as the emergence of secret video and audio recordings has shown.12He was surveilled in private and with visitors, including family, friends, journalists, lawyers, and doctors. Not only were his rights to privacy, personal life, legal privilege, and freedom of speech violated, but so, too, was his right to doctor–patient confidentiality.

We condemn the torture of Assange. We condemn the denial of his fundamental right to appropriate health care. We condemn the climate of fear surrounding the provision of health care to him. We condemn the violations of his right to doctor–patient confidentiality. Politics cannot be allowed to interfere with the right to health and the practice of medicine. In the experience of the UN Special Rapporteur on Torture, the scale of state interference is without precedent: “In 20 years of work with victims of war, violence and political persecution I have never seen a group of democratic states ganging up to deliberately isolate, demonise and abuse a single individual for such a long time and with so little regard for human dignity and the rule of law.”7,12

We invite fellow doctors to join us as signatories to our letters to add further voice to our calls. Since doctors first began assessing Assange in the Ecuadorian Embassy in 2015, expert medical opinion and doctors’ urgent recommendations have been consistently ignored. Even as the world’s designated authorities on arbitrary detention, torture, and human rights added their calls to doctors’ warnings, governments have sidelined medical authority, medical ethics, and the human right to health. This politicisation of foundational medical principles is of grave concern to us, as it carries implications beyond the case of Assange. Abuse by politically motivated medical neglect sets a dangerous precedent, whereby the medical profession can be manipulated as a political tool, ultimately undermining our profession’s impartiality, commitment to health for all, and obligation to do no harm.

Should Assange die in a UK prison, as the UN Special Rapporteur on Torture has warned, he will have effectively been tortured to death. Much of that torture will have taken place in a prison medical ward, on doctors’ watch. The medical profession cannot afford to stand silently by, on the wrong side of torture and the wrong side of history, while such a travesty unfolds.

In the interests of defending medical ethics, medical authority, and the human right to health, and taking a stand against torture, together we can challenge and raise awareness of the abuses detailed in our letters. Our appeals are simple: we are calling upon governments to end the torture of Assange and ensure his access to the best available health care before it is too late. Our request to others is this: please join us.

We are members of Doctors for Assange. We declare no competing interests. Signatories of this letter are listed in the appendix.

Published at https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(20)30383-4/fulltext?rss=yes