By Glenn Greenwald

Former Ecuadorian President Rafael Correa, in an exclusive interview with The Intercept on Wednesday morning, denounced his country’s current government for blocking Julian Assange from receiving visitors in its embassy in London as a form of “torture” and a violation of Ecuador’s duties to protect Assange’s safety and well-being. Correa said this took place in the context of Ecuador no longer maintaining “normal sovereign relations with the American government — just submission.”

Correa also responded to a widely discussed Guardian article yesterday, which claimed that “Ecuador bankrolled a multimillion-dollar spy operation to protect and support Julian Assange in its central London embassy.” The former president mocked the story as highly “sensationalistic,” accusing The Guardian of seeking to depict routine and modest embassy security measures as something scandalous or unusual.

On March 27, Assange’s internet access at the Ecuadorian Embassy in London was cut off by Ecuadorian officials, who also installed jamming devices to prevent Assange from accessing the internet using other means of connection. Assange’s previously active Twitter account has had no activity since then, nor have any journalists been able to communicate with him. All visitors to the embassy have also been denied access to Assange, who was formally made a citizen of Ecuador earlier this year.

Assange has been confined to the embassy for almost six years, when Ecuador granted him asylum in August 2012. The grant of asylum was made on the grounds that Assange’s extradition to Sweden for a sexual assault investigation would likely result in being sent to the U.S. for prosecution, where he could face the death penalty.

From the start, Ecuador told both the U.K. and Swedish governments that it would immediately send Assange to Stockholm in exchange for a pledge from Sweden not to use that as a pretext to extradite him to the U.S., something the Swedish government had the power to do but refused.

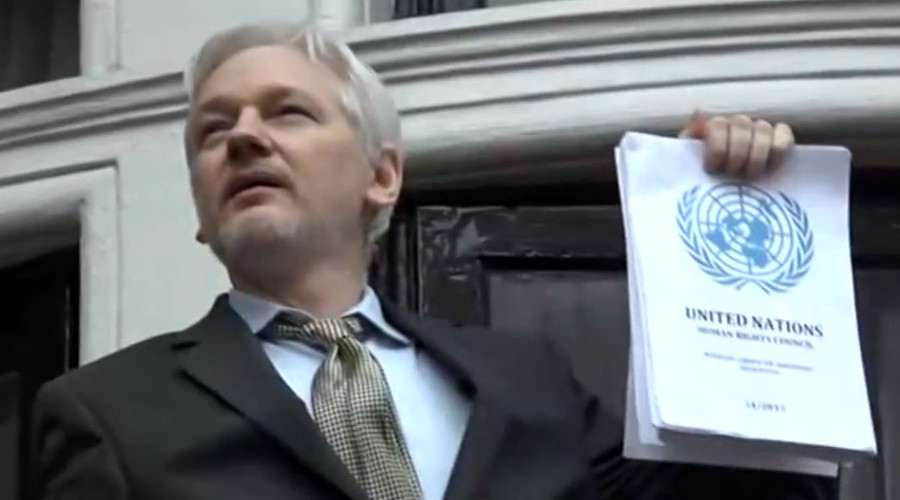

Correa also emphasized that Ecuador, from the start, told Swedish investigators that they were welcome to interrogate Assange in their embassy, but almost five years elapsed before Swedish prosecutors — in 2016 — finally did so. Citing those facts, a United Nations panel ruled in 2016 that the actions of the U.K. government constituted “arbitrary detention” and a violation of Assange’s fundamental human rights, a decision British officials quickly said they intended to ignore.

Despite the fact that Swedish prosecutors dropped its sex crimes investigation last May (not because they concluded Assange was innocent, but because they believed further efforts to bring him to Sweden were futile), U.K. authorities have vowed to arrest him on what it claims are bail violations.

The danger for Assange thus remains high if were to leave the embassy, particularly in light of a highly threatening speech given last year by Mike Pompeo, then U.S. President Donald Trump’s CIA director and now his secretary of state, in which he labeled WikiLeaks a “non-state hostile intelligence service,” denied that its publication of documents is protected by the First Amendment, and vowed that “to give them the space to crush us with misappropriated secrets is a perversion of what our great Constitution stands for. It ends now.”

In January, doctors who examined Assange inside the embassy warned that continued confinement posed grave threats to both his physical and mental health. Assange’s mother said earlier this week that his health was “rapidly deteriorating” and had become “extremely dangerous.”

Correa cited those facts, as well as Ecuador’s legal obligations under international law to asylees, to denounce Ecuador’s denial of visitors to Assange as “basically torture.” Denial of visitors is, Correa said, “a clear violation of his rights. Once we give asylum to someone, we are responsible for his safety, for ensuring humane living conditions.” But “without communications to the outside world and visits from anyone, the government is basically attacking Julian’s mental health.”

The ex-president said he believed it could be appropriate to limit Assange’s communications if he were acting “irresponsibly” by interfering in another country’s politics. During the 2016 U.S. election, Correa said, his own government told Assange that it thought his attacks on Hillary Clinton were becoming excessive and briefly suspended his internet connection to underline its concerns.

“But that was just temporary,” said Correa. “We never intended to take away his internet for an extended period of time. That is going way too far.” Correa’s Foreign Affairs Minister Guillaume Long similarly said in an interview with The Guardian earlier this morning that he, too, believed that the denial of visitors to Assange and the blocking of his internet access for this long — believed to be due to Assange’s frequent tweeting over the Catalan independence movement in Spain — was unjust.

As for reports that Ecuador is negotiating with the U.K. government to turn over Assange, Correa said that he had no knowledge of those discussions, but said it would be “unthinkable” for Ecuador to do so without first obtaining enforceable protections for Assange’s rights, including not having the U.K. government use the bail violations as a pretext to hand over Assange to the U.S.

Emphasizing that the U.S. government has made clear that it wants to prosecute Assange for publishing newsworthy material under statutes that allow for the death penalty, Correa said any such deal that did not include protections against extradition to the U.S. would be “a terrible betrayal, a violation of the rules of asylum, and a breach of Ecuador’s responsibility to protect the safety and welfare of Julian Assange.”

During his presidency, Correa was particularly assertive about defending the sovereignty of his country from intrusions by more powerful states, particularly the U.S. In 2007, he ordered a U.S. military base on Ecuadorian soil closed unless the U.S. was willing to allow Ecuador the reciprocal right to establish a military base in Miami.

But earlier this month, Correa’s successor, the current Ecuadorian President Lenín Moreno, announced that it had “recently signed an agreement focused on security cooperation [with the U.S.] which implies sharing information, intelligence topics and experiences in the fight against illegal drug trafficking and fighting transnational organized crime.” Many in Ecuador viewed that as a prelude to a return to the days when the U.S. dominated Ecuador, including with new military bases, a suspicion Moreno’s government denies.

But to Correa, Moreno is returning Ecuador to the days when it was subservient to the dictates of the U.S. government. “Everyone in Latin America knows what this agreement with the U.S. means control, intervention, spying,” he said. Given the submissive posture of the current Ecuadorian president, Correa said it would not shock him if they submitted to American and British demands regarding Assange. Correa also cited the Moreno government’s recent decision to terminate peace talks between the Colombian government and rebels on Ecuadorian soil, which the ex-president believes was done at the behest of the U.S.

As for the “spying” allegations in the Guardian article, Correa said that the newspaper took a customary and standard security arrangement, and tried to make it appear sinister and scandalous. “Of course we provided security to Assange in the embassy,” Correa said. “It was our duty under the law to do so. We had the U.K. government threatening to break into the embassy. We spent what amounts to a small amount of money to provide security.”

Correa said that unlike the U.S., which surrounds its embassies with massive military protection, Ecuador does not have the means to do that. “So, when we have special security needs, we hire private firms to provide it. There is nothing unusual about this. It would have been a violation of our duties if we did not.” Correa said his government hired a well-known security firm based in Spain, UC Global, to provide those services, but the current government replaced it with an Israeli firm. “But those services are still being provided by the current government,” Correa said.

As for The Guardian’s claim that Assange himself breached Ecuadorian cybersecurity systems to read emails and documents from Ecuadorian officials, Correa said the claim seemed “absurd,” adding that The Guardian “presented no evidence for this, just an anonymous source.” Conceding that it was possible that Assange had managed to hack into various government systems, he emphasized that he had no knowledge that any such spying by Assange had taken place nor has he seen any evidence for this claim.

The former president stressed that he had been given virtually no chance to respond to The Guardian’s allegations before publication of its article. “They sent it to some email address in Ecuador very shortly before they published the story,” said Correa, who is currently in Belgium. “I did not see the email until after the story was published. They seemed to want to make a sensationalized story, not any serious report to find out the truth.” Correa said he would provide The Intercept with the email sent by The Guardian; upon receipt from Correa, this article will be updated to include it.

Correa continues to believe that asylum for Assange is not only legally valid, but also obligatory. “We don’t agree with everything Assange has done or what he says,” Correa said. “And we never wanted to impede the Swedish investigation. We said all along that he would go to Sweden immediately in exchange for a promise not to extradite him to the U.S., but they would never give that. And we knew they could have questioned him in our embassy, but they refused for years to do so.” The fault for the investigation not proceeding lies, he insists, with the Swedish and British governments.

But now that Assange has asylum, Correa is adamant that the current government is bound by domestic and international law to protect his well-being and safety. Correa was scathing in his denunciation of the treatment Assange is currently receiving, viewing it as a byproduct of Moreno’s inability or unwillingness to have Ecuador act like a sovereign and independent country.