Philip Chrysopoulos

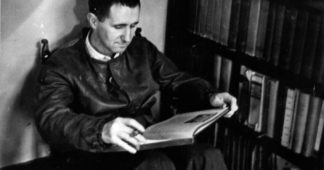

Konstantinos Kavafis — or Constantine Peter Cavafy as he was internationally known — was one of the greatest Greek poets.

He was born in Alexandria, Egypt on April 29, 1863, the last of nine children of the wealthy merchant Petros-Ioannou Kavafis. He died on the very same date seventy years later, in 1933.

In a short autobiography, Kavafis wrote of his life:

“I hail from Constantinople, but I was born in Alexandria – in a house on Sherif Street. When I was very young I left and spent much of my childhood in England. I visited this country after a long time but stayed for a short while. I lived in France too. In my teenage years, I lived for over two years in Constantinople. I had not visited Greece for many years. My last job was as an employee of a government office of the Egyptian Ministry of Public Works. I speak English, French, and a little Italian.”

Incredibly, the man known above all else for his poetry Kavafis never published his poems in book form during his lifetime.

Instead, he preferred to give them to newspapers and magazines to publish, or simply handwrote them and gave them away to anyone who was interested.

Beloved Alexandria was Kafavis’ base

He wrote 154 poems and dozens of sketches and left behind a number of unfinished pieces. The first book of his poems was only published in 1935, two years after his death.

Kavafis lost his father at the age of seven, the death forcing his mother Harikleia to take the family and move to London, and then to Liverpool.

The young Konstantinos learned English and cultivated an interest in literature early on in life. However, financial problems forced the family to move again in 1878, this time back to Alexandria.

In 1882 the nationalist riots in Egypt prompted the Kavafis family to relocate yet again, but to Constantinople this time. He made his first systematic efforts to write poetry during his stay in this great city, with the very first poem in his archives appearing to have been written in 1882.

The works “Beizades to His Mistress” (1884), “Dunya Guzeli” (1884) and “Nihori” (1885) show how deeply the Byzantine city had inspired him.

In October of 1885 Kavafis returned to Alexandria, along with his mother and his two brothers, Alexander and Paul, after receiving compensation for the destructive riots of 1882.

One of his first decisions upon his return there was to acquire Greek citizenship. Kavafis then began to work, first as a journalist and then as a broker at Egypt’s Cotton Stock Exchange.

In 1889, he was initially recruited to work as an unpaid secretary to the country’s Irrigation Service; in 1892 he became a salaried employee there, a post in which he would remain until 1922, even reaching the rank of Deputy Mayor.

In 1891, Kavafis saw his first remarkable poem “Builders,” published. He wrote some of his most important pieces, such as “Candles” (1893), “Walls” (1896) and “Waiting for the Barbarians” (1899) from 1893 until the end of the century.

The poet’s mother passed away in 1899, and Kavafis wallowed in his grief for a long period of time.

In 1902 Kavafis traveled to Greece for the very first time in his life; it was in Athens where he met his future colleagues Grigorios Xenopoulos and Ioannis Polemis.

In a letter he wrote upon arriving in the Greek capital, he said he felt like a Muslim pilgrim who travels to Mecca.

He visited Athens again during the next year, and on Nov. 30 of the same year, Xenopoulos wrote the historical article “A Poet,” which appeared in Panathenaea magazine.

This was the first time Kavafis’ work had received any attention and praise from the Greek public.

Kavafis settled in the house at 10 Lepsius Street in Alexandria, where he would spend the rest of his life writing the most important poems of his oeuvre, in December of 1907.

With his literary reputation on the rise, he received a number of renowned visitors to his home, including Tommaso Marinetti, Andres Malraux, Nikos Kazantzakis, Kostas Ouranis and Myrtiotissa.

Kavafis and his famous poem, “Ithaca”

In 1911, Kavafis wrote his famous poem, “Ithaca.” Three years later, he met the great English novelist Edward Morgan Forster and became friends with him; five years later, Forster would introduce the poetry of Kavafis to the English-speaking world.

Kavafis was finally able to resign from his work as a public servant to dedicate himself to his poetry in April of 1922.

“At last, I was released from that hateful thing,” he later wrote.

In the following year the poet’s last living brother, John Kavafis, who had been the first admirer and translator of Konstantinos’ work, passed away.

In 1926, the Greek government awarded Kavafis their greatest honor, the Medal of the Order of the Phoenix.

He began to suffer from problems with his larynx and doctors diagnosed cancer in 1930.

Kavafis soon found himself unable to speak, and in 1932 he was subjected to a tracheotomy operation in Athens.

The poet returned to Alexandria, with his health constantly deteriorating, in 1933. In early April he was transferred to the Hellenic Hospital and at 2 AM on April 29, 1933, the poet breathed his last breath at the age of 70.

Kavafis brought an international aura to modern Greek poetry

Scholar Maria Akritidou wrote about the great man’s work “Konstantinos Kavafis is a hypermodern poet, a poet for later generations.”

“Apart from its historical, psychological and philosophical value, the austerity of his style, which sometimes touches on laconism, his weighted enthusiasm that appeals to emotional intellectualism, his correct phrasing, the result of a classy naturalness, his slight irony, represent elements which will be further appreciated by future generations, motivated by the progress of the discoveries and the subtlety of the mental mechanism.”

Greece 2021, the organization which organizes the events of the Greek Bicentennial, wrote about Kavafis:

“The ‘Alexandrian’ (1863-1933) brought an international aura to modern Greek poetry. Modern, even before modernism was a term, a scholar and an aesthetician, a realist, and lover of detailed verse. He compelled Greek poetry with his hedonistic, esoteric sentiment in the social context of the time. He glorified beauty and pleasure of the flesh.

“He was a master at saying a lot with very little. His style was ironic, esoteric, unrhymed, focused on detail and precise expression, qualities that made him a novelty among the poets of his time. Although his bibliography is rather small, just 154 published poems, it is an inexhaustible field for humanistic and poetry studies.”

Published at greekreporter.com

We remind our readers that publication of articles on our site does not mean that we agree with what is written. Our policy is to publish anything which we consider of interest, so as to assist our readers in forming their opinions. Sometimes we even publish articles with which we totally disagree, since we believe it is important for our readers to be informed on as wide a spectrum of views as possible.