The impulse to punish Putin for his unconscionable invasion of Ukraine is understandable, but wrecking entire economies comes at a high human cost.

By Sarah Lazare

On February 24, the day Russia began its invasion of Ukraine, the U.S. Congressional Progressive Caucus released a statement condemning Russia’s “war of aggression” and expressing solidarity with the Ukrainian people, while sounding a note of caution about any U.S.-imposed sanctions. “The goal of any U.S. sanctions should be to stop the fighting and hold those responsible for this invasion to account, while avoiding indiscriminate harm to civilians or inflexibility as circumstances change,” the statement read.

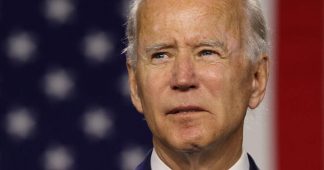

But in the days since this statement was released, the United States has imposed broad, economy-wide sanctions that have caused Russia’s currency, the ruble, to fall 29% over the weekend, Russian stock markets to plummet, and panicked residents to wait in long lines to withdraw funds from their accounts. The Biden administration is open about the fact that the goal of these sanctions is to tank Russia’s economy, in retaliation for Putin’s stunning violence in Ukraine. “We are united with our international allies and partners to ensure Russia pays a severe economic and diplomatic price for its further invasion of Ukraine,” the U.S. Treasury Department declared last week.

But some anti-militarist organizers and rights activists warn that responding to Russia’s aggression with economic warfare could cause even more harm — and cost lives.

“We should oppose, reject and condemn Putin’s illegal and obscene war on Ukraine,” Tobita Chow, the director of the advocacy organization Justice Is Global, tells In These Times. (Disclosure: Chow is a board member of In These Times.) “But I have a number of fears with these sanctions which are causing a currency crisis, hurting millions of Russian people, and possibly inflicting severe long-term damage to the Russian economy.”

While it’s difficult to know yet the full impact sanctions will have on Russian civilians, the shockwaves are poised to be far-reaching. On February 24, the U.S. Department of Treasury announced it was imposing sanctions on “Russia’s top financial institutions, including sanctioning by far Russia’s two largest banks and almost 90 financial institution subsidiaries around the world.” The next day, the United States, European Commission, France, Germany, Italy, the United Kingdom and Canada announced that they would remove Russian banks from Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication (SWIFT), an international messaging system owned by banks in Belgium that enables the transfer of money between large financial institutions and is critical for certain kinds of global trade. On Friday, French Economy and Finance Minister Bruno Le Maire called this move “the financial nuclear weapon.”

And on February 28, the U.S. Treasury Department announced it was banning all transactions with Russia’s central bank (with exceptions for “certain energy-related transactions”). “Under the new regime, all people in the United States and European Union are banned from trading with Russia’s central bank,” Jeff Stein and Robyn Dixon summarized for the Washington Post. Secretary of the Treasury, Janet Yellen, said the sanctions will “significantly limit Russia’s ability to use assets to finance its destabilizing activities, and target the funds Putin and his inner circle depend on to enable his invasion of Ukraine.”

These sanctions and penalties come in addition to those targeting oligarchs, along with Russian officials, including President Putin, as well as the country’s Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov. But what makes the economic sanctions so notable is their breadth: They are not “targeted,” to the extent that is possible, but are rather designed to inflict economy-wide harm. The sanctions are being hailed as “unprecedented” by the Biden administration and, indeed, never have such sweeping economic punishments been imposed on a state that possesses nuclear weapons.

The disastrous consequences these sanctions unleash on regular people are already apparent, with NPR describing the result as “economic turmoil” in its headline. Interest rates at Russia’s central bank more than doubled, the Moscow Exchange is closed until March 5, and ordinary Russians express fear and despair as they frantically purchased goods before prices shoot up even more. When the Treasury Department talks about a “severe economic price,” such hardship — and worse — is implicit in the threat.

Given the understandable desire to “do something” to punish Russia, there’s been very little public debate about the actual harms these sweeping policies will bring. This is a point the Ukrainian Foreign minister himself was more that willing to spell out on social media, presumably in an effort to convince Russian English language Twitter users to rise up and overthrow their government:

“Ordinary Russian citizens have not yet realized that Russia’s attack on Ukraine will affect them personally. Sanctions do not only apply to oligarchs. Each and every Russian will feel them. Hyperinflation, deficits, queues, devaluation of savings, unemployment. Russians, wake up!”

For clues on what the impact economic sanctions could have on the Russian people, it is helpful to look at Iran. That country has faced both sanctions placed on major banks and financial institutions, as well as suspension from the SWIFT system, most recently in 2018 when SWIFT ceded to pressure from the Trump administration. (Iran was also partially cut off from SWIFT in 2012.) The consequences have been severe. In 2019, Human Rights Watch released a report which found that, “Though the U.S. government has built exemptions for humanitarian imports into its sanction regime, broad U.S. sanctions against Iranian banks, coupled with aggressive rhetoric from U.S. officials, have drastically constrained Iran’s ability to finance such humanitarian imports.” The result, the report found, was a catastrophic lack of access to essential medicines, “ranging from a lack of critical drugs for epilepsy patients to limited chemotherapy medications for Iranians with cancer.”

Ryan Costello, policy director for the National Iranian American Council, an advocacy organization, tells In These Times that there are significant similarities between the sanctions the United States has imposed on Iran and those it is imposing on Russia. “There are a lot of similarities to Iran sanctions. But Iran is much less of a central player: They don’t have nuclear arms, don’t have a conventional military the same way Russia does. We don’t exactly know what U.S. involvement in economic escalation could lead to with Russia. In Iran, it punished civilians who don’t have control of their government, and caused hyper-inflation in the Iranian economy.”

The cutting off of Russia’s central bank, meanwhile, has a more immediate parallel in Afghanistan, where the U.S. seizure of the country’s central bank assets in response to the Taliban taking power is dramatically worsening a crisis of poverty and famine. While Afghanistan is a far poorer country than Russia, banning trade with Russia’s central bank still threatens the wellbeing and livelihood of countless Russians. And it also, in principle, undercuts the demands of progressive lawmakers who are calling for reserves to be returned to Afghanistan.

It’s unclear if a Russian withdrawal from Ukraine could stave off these broad sanctions since U.S. officials haven’t explicitly indicated this would trigger a pullback. But given that Putin can decide at any minute to end the invasion, his ceasing this war of choice would be the most elegant solution to stopping the sanctions. But in light of the fact he has given no immediate indication he plans to do so, those in the West should be sober about the consequences that “crippling” the Russian economy will bring for Russian people — both those in Russia and abroad.

“I think that the economic turmoil will certainly have a humanitarian effect, so that’s something I would be concerned about,” Kevin Cashman, a Senior Associate at the Center for Economic and Policy Research (CEPR), a left-leaning think tank, tells In These Times. “There are carve outs they’re still considering for oil and gas, because Europeans need to buy it. But if Russians can’t get remittances or can’t conduct business, that’s going to hurt everyone.”

“Iran has somewhat dealt with that by building alternatives in bartering or getting partners in countries willing to do business with them,” Cashman says. “It remains to be seen how Russia is going to do that. But no matter what, there are going to be humanitarian consequences. The ruble is devaluing pretty quickly. It’s going to hurt a lot of Russians — Russians who have nothing to do with what the leadership is doing in Ukraine and elsewhere.”

It is difficult to know, at this point, exactly what this humanitarian cost could look like, but there is reason to be concerned. According to an estimate from the Brookings Institution, between May and September 2020 13,000 Iranian deaths were caused by U.S. sanctions being imposed during a pandemic. An analysis from CEPR, meanwhile, estimated that sanctions were responsible for at least 40,000 deaths from 2017 to 2018 in Venezuela. This does not mean Russia will necessarily face the same consequences, but a free-falling economy will certainly claim innocent victims. This is bleakly ironic in a country where residents have braved repression to protest the war that Putin is waging.

The obvious question of what can be done to encourage Russia to withdraw in lieu of heavy handed sanctions that will harm Russia’s most vulnerable is a fair and difficult one to answer. Diplomacy and de-escalation are the obvious response, anti-war activists say. But it’s important to note that the United States isn’t “doing nothing” — it provided Ukraine $650 million in military aid over the past year, the CIA has been training Ukrainian special forces since 2015, and Congress is likely to approve another $3.5 billion in additional military aid any day now—roughly the annual defense spending of the Philippines.

Meanwhile, Chow expresses concern that the sanctions could have other unforeseen impacts — namely, escalation. “I fear they may only increase Putin’s desperation and trigger escalation against Ukraine, possibly increasing nuclear risks,” he says.

Chow adds, “I fear the likelihood that Putin will be able to use this to increase the power of Russian nationalism — blaming all of Russians’ suffering on the West, saying, ‘You are either with Russia or with the U.S., NATO and EU,’ that he will then use to legitimize escalating attacks on antiwar protesters and critics within Russia.”

“Ramón Mejía, an anti-militarism national organizer with Grassroots Global Justice Alliance, a social movement organization, says he believes sanctions are “used in the U.S. to appease the public, to maintain the image that the U.S. is still this super power. But they will not bring about the results they’re intended to bring.”

“Sanctions result in devastating impacts on not only health,” he says, “but the wellbeing of communities that sanctions are imposed on.”

Josh Mei contributed research to this article.

* Sarah Lazare is web editor and reporter for In These Times. She tweets at @sarahlazare.

Published at inthesetimes.com

We remind our readers that publication of articles on our site does not mean that we agree with what is written. Our policy is to publish anything which we consider of interest, so as to assist our readers in forming their opinions. Sometimes we even publish articles with which we totally disagree, since we believe it is important for our readers to be informed on as wide a spectrum of views as possible.