As he United Kingdom exits the eu, the political scene has all the trappings of a restoration. The Tories are back in office with their largest majority since the 1980s, thanks to the long-ignored northern working class. The uk is resuming the offshore relationship to the project of European integration it had in the 1960s. The Prime Minister is a reversion to type: Old Etonian, former editor of the Spectator, author of The Churchill Factor (even if his family background is more cosmopolitan-bohemian than landed-capitalist). Johnson likes to be photographed in front of two Union Jacks and effortlessly assumes his hero’s neckless-bulldog pose, brightened by a blonde Beatles mop. Aspects of a traditional ruling-class persona—decisiveness, vitality, enjoyment—were foregrounded in Johnson’s ‘Get Brexit Done’ election campaign, which cut the Gordian knot of a political crisis that pitted Parliament against the Prime Minister, the Supreme Court against the Crown, Holyrood against Westminster, London against the North. ‘A second referendum is no longer an issue’, Labour’s Shadow Brexit Secretary confirmed the day after the election.

Symbols matter. But the nature of Johnson’s ascendancy is best grasped through the multiple crises—economic, social, regional, national, European—to which it presents a solution. Chronologically, the story is simple enough. The knell of what appeared to be a long period of political and economic stability was first sounded in the City of London, with the financial meltdown of 2008. Recession and social crisis intensified from 2010, when the Cameron–Clegg government complemented City bailouts with fee hikes for students and pro-cyclical austerity, deepening the regional immiseration of the deindustrialized north. From 2011, the Eurozone crisis inflated the uk’s social inequalities: capital fleeing to the safety of the London property market, unemployed eu workers to agency jobs in the hinterlands. The eu question, previously low among voters’ priorities, began its climb up the national agenda.

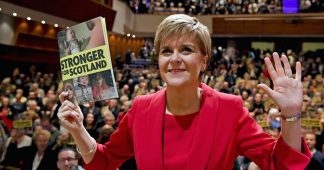

From this point, four political alternatives opened up. The first was ukip’s call for a national-independence struggle against Brussels rule. The funds and cadre for this movement were supplied by City mavericks; its initial base was older Tory voters, especially in the market-town south. Second, Scotland’s demand for national self-determination, fuelled by opposition to English-Tory austerity. The radical, youth-led ‘Yes’ campaign took on the character of a social movement, mobilizing the old working-class heartlands in Dundee, Glasgow and Strathclyde.footnote1 The third challenge came from the Labour Left under Jeremy Corbyn: an appeal to redistribute wealth and recast foreign policy, distancing the uk from nato’s wars. Corbyn’s base was cut from the same socio-economic cloth as the Scottish #IndyRef campaign: young, university-educated, semi-precariat. The fourth position, defence of the status quo, was in principle the most powerful; among its supporters were the liberal intelligentsia and all those who benefited from things as they were. From 2014, the struggles between these competing alternatives would extend the uk’s complex crisis into its party system and multi-national state, questioning its relations with the eu and position in the Atlantic order.

Class-region configurations

The City, eu, nato alliance, multi-national state, Westminster party system; classes, regions, parties, voters—how should these multiple structures and agents be articulated? This question was addressed by Tom Nairn in 1981; and although his elegant account of the national compact needs updating, its lineaments are still highly relevant today.footnote2 Nairn argued that the country’s early capitalist development and overseas expansion under a powerful landowning class had given a uniquely outward-oriented cast to the post-1688 state, which the world’s first industrial revolution then powered to global predominance. The initial class configuration remained intact: the manufacturing bourgeoisie, concentrated in the north, was socially and politically subordinate to the southern landowning aristocracy, under an oligarchic parliamentary system that pre-dated universal suffrage. There was no struggle for national self-determination, no modernizing second revolution—nothing to compare to the galvanizing effects of Bismarck’s Germany, the us Civil War or Meiji Japan. Instead, the rising bourgeoisie was absorbed into the existing aristocratic state and civil structures.

The world dominance of the City of London served to divert investment away from the northern industrial regions: higher returns were to be found overseas. The upshot was the asymmetry of class and region described in Hobson’s Imperialism: a nation polarized into a smaller, industrialized north and a larger, consumption-oriented south, living off the proceeds of empire, whose ‘well-to-do classes mould the external character of the civilization and determine the habits, feelings and opinions of the people’, while labour is ‘closely and even consciously directed by the will and the demands of the moneyed class’.footnote3 The Labour Party, Nairn argued, accommodated itself to the hegemony of the metropolitan heartlands, seeking only a compromise formula of better wages and welfare provision, under a continuing ‘outward-looking over-balance’ of uk capitalism that deprived small manufacturing firms—the German Mittelstand—of adequate investment and technical support.

Under Thatcher, Nairn wrote, southern hegemony ‘appears naked’. The southeast was increasingly a service zone for international speculation, insurance and re-investment. What remained of northern manufacturing could be sold off to us, German or Japanese multinationals. Outward investment soared with Thatcher’s abolition of exchange controls, as did domestic bankruptcies, in a dramatic acceleration of the old extraverted state strategy. ‘Decline’, the long-standing British affliction, was no longer a national phenomenon: it was regionalized, concentrated in the north. The national questions of Scotland, Wales and Ulster, Nairn now argued, should be seen as lodged within the uneven development of the north–south divide, produced by the external orientation of the state.footnote4

One aspect Nairn did not explore was the contradictory post-imperial world position of the uk. Here, the three zones of global influence identified by Churchill—dominion over the empire, partnership with the us, offshore balancer for continental Europe—had been turned inside out. By the start of the 21st century, the uk had surrendered military and geopolitical sovereignty to the us in order to participate (albeit with subordinate status) in continuing global predominance; it occupied a semi-detached position in relation to Europe: a member of the eu, but firmly outside the Eurozone and Schengen Area. Meanwhile, the south-of-England hegemony Nairn described has been inflated by successive asset bubbles, courtesy of the Federal Reserve, that have poured trillions into the financial sector and pumped up the overall position of the City. Within the eu, the uk state loosened its sub-national borders—devolved parliaments in Scotland and Wales, the Good Friday Agreement—and accommodated itself to the growing body of European law.

Internally, two generations of asset inflation, wage stagnation and globalized investment have led to a disaggregation of class blocs, above and below. Within the ruling bloc itself, the layers organized around the City have grown astronomically rich and increasingly globalized. While London remained the financial capital of Europe, ‘outward-orientation’ in the era of bubblenomics was above all Atlanticist. City institutions set the course for Britain’s increasingly extraneous relation to the eu by blocking accession to the single currency under New Labour; money-making could proceed more freely with another sovereign currency to juggle, and beyond the purview of Condorcet-reading French regulators.footnote5 Meanwhile the powerful political and intellectual establishment—House of Lords, Supreme Court, upper reaches of the bbc and civil service, ‘great and good’—also gained from London’s rising asset values; but in their case, a general sympathy with Atlanticist liberal internationalism was more qualified by ideological scruples (Bush, Trump). Though it had never shown much interest in the development of the eu as a polity, this layer would react passionately against the loss of Europe. The greatly weakened manufacturing sector, having endured a long slump through the high-currency New Labour years, struggled to make the most of a weaker pound after 2008; it was barely a player in what followed.

The working classes and middle strata have been disaggregated, too, by region, generation, university education, wage stagnation, asset ownership and internal migration. Privatized council housing yielded differential gains, as prices soared in the big cities and the south. Growth and service-sector jobs were concentrated in London and the other major urban areas, producing a young, precarious, multi-ethnic wage-earning class—‘university-educated, highly indebted, destined to spend the rest of our lives renting expensive property from a series of landlords’footnote6—leaving the old manufacturing and mining districts bereft. The sub-nations of Scotland, Northern Ireland and Wales replicated their own versions of these patterns.

This was the divided, ‘over-balanced’ national-class configuration hit by the multiple crises of the 2010s. Of the political alternatives on offer, each aimed to mobilize a class coalition behind its own solution to the questions of the eu, nato, southern-based financialized capitalism and the multi-national state. The Scottish rebellion briefly united the educated youth with the old working class, as Neil Davidson details.footnote7 Strongly pro-Europe, it was more critical of nato and the Trident nuclear submarines, and broadly social-democratic. The Corbyn campaign, whose most active layers were young and southern-based, hoped to create a similar alliance for a redistribution of wealth, a partial re-nationalization of assets and stimulus through green new deal initiatives; Corbyn’s critique of nato was barely audible, drowned out by accusations of terrorist sympathies and antisemitism. Split on Europe, Labour developed neither a radical Remain nor a plausible Lexit position. For their part, ukip and Leave.eu aimed to unite elderly southern Tory voters with the northern working class—‘England without London’, as Anthony Barnett has called it—in their belated national-independence struggle.footnote8 For them, however, independence from nato was never in question. Strongly unionist, they were divided on political-economic questions between a free-market, ‘Singapore-on-Thames’ approach and state-interventionist national consolidation.

In the general election of 2015, the youth-led revolt against austerity punished Scottish Labour for its No role in the Independence Referendum, and reduced the Liberal Democrats to single digits in the Commons for raising student fees. From the right, Cameron mobilized an ‘England against Scotland’ campaign, scaring voters with the prospect of a Labour–snp alliance, to clinch a small majority in the Commons. He had successfully seen off the Scottish revolt the year before by radicalizing the question—insisting the referendum be held on full independence, not maximum devolution—and threatening that Scots would no longer be allowed to use the British currency. Now he applied the same trick to the eu: not a vote on the latest treaty, but a full in-out referendum. The Brexit vote famously divided the country along sub-national, social, regional, class and generational lines. London, Scotland, Northern Ireland, the big cities, the middle class and the youth voted to stay in the eu; the bulk of ‘England without London’, Wales, the small towns, the working class and the elderly voted to leave, by a majority of 52:48.footnote9

The Brexit vote constituted a further dimension of crisis, this time for the political establishment as a whole. Operative respect for democracy would run counter to the entire cast of government policy and state administration, involving a wrenching re-orientation of the Whitehall machine. The liberal intelligentsia was devastated, far more so than it had been by the ravages of Thatcherism or by Blair’s mad-dog wars. Thomas Piketty’s description, quoted by a contributor to the lrb’s ‘What have we done?’ issue—Brexit was a moment of ‘collective unreason’, ‘profoundly nihilistic and irrational’—summed up the mood.footnote10 Yet it is striking that, in governing circles, a consensus at the top was nevertheless reached quite quickly. Brexit would go through, Cameron announced, even as he resigned, to be replaced as prime minister by Theresa May. One reason for this assent was the idea of a ‘Treasury version’ of Brexit-lite: Norway-plus, free access for financial services, ‘reasonable’ restrictions on migrant workers that other eu countries would probably welcome for themselves. A second, related reason was that the uk was in many respects already outside the core workings of the eu, which crucially concern the management of the Eurozone. Third, political competition: Leave voters constituted 61 per cent of the Tory vote, and ukip was waiting to recruit them at the first sign of ‘betrayal’. Reluctantly, in 2016–17 the bulk of the establishment came to terms with trying to make the best of Brexit, signalled by leader writers across the quality press.

An existential threat?

There was no question of a comparable coming-to-terms with the alternative represented by Corbyn. From the start, the Labour leader came under an unprecedented three-way assault—from the establishment intelligentsia, from his own parliamentary party and from opponents of his anti-war foreign policy. ‘If ever an election needed a bit of fixing, it was this one’, wrote David Runciman in the lrb in the summer of 2015, as Corbyn’s popularity became apparent.footnote11 Once elected as leader he was immediately under fire—over the Trident nuclear programme, bombing of Syria, lacklustre local-election performance—while his mps shouted abuse at him in the corridors of Westminster. In June 2016, Labour mps informed the bbc that, as a secret or cynical Brexiteer, he had ‘deliberately sabotaged’ the eu referendum and should be held personally responsible for the outcome. Three-quarters of the Parliamentary Labour Party staged a vote of no confidence in him.footnote12

Opponents of Corbyn’s anti-war position tended to avoid direct confrontation—his suggestion, following the 2017 Manchester bomb attack, that British foreign policy in the Middle East bore some responsibility for the rise of Islamist terror, would draw broad support—and sought instead to tar him with antisemitism. As Avi Shlaim has documented, the groups trawling social media for posts to use against him—with the backing of the Israeli Embassy, run by a former pr man of Netanyahu—included the Zionist Federation, which previously specialized in disrupting student meetings on the Middle East, and the Campaign against Antisemitism, set up in 2014 to counter critics of Israel’s Gaza War, which targeted Jewish supporters of Corbyn in particular, and any media outlets that gave them an airing—as in the caa headline from April 2019, ‘Radio Times publishes Miriam Margolyes’s vile claims that antisemitism in the Labour Party is exaggerated “to stop Corbyn from being Prime Minister”’.footnote13

The campaign’s claims that the Labour Party under Corbyn was ‘institutionally racist’ and posed ‘an existential threat’ to Jewish life in Britain were given full-blown coverage by the mainstream press. Between June 2015 and March 2019, there were nearly 5,500 articles on Corbyn and antisemitism across the major uk newspapers.footnote14 The campaign intensified after Labour’s surprise success in the 2017 election. Day after day, headlines blazed from the newsstands: ‘corbyn’s labour riddled with antisemites’—‘labour’s antisemite army’.footnote15 The bbc News consistently led on the story. Focus groups confirmed the campaign’s success: voters estimated that around a third of Labour members must have been charged with antisemitism (the actual figure for valid reported cases was 0.06 per cent of the membership), and were particularly angry that ‘Corbyn never apologized’ (he did). A minority—perhaps courtesy of the Daily Mail—had heard that Corbyn was going to introduce sharia law.footnote16

In September 2018, analysis of 250 newspaper articles and tv news items on these themes found 95 clear-cut cases of misleading or inaccurate reporting, with two-thirds of tv news items containing reporting errors or substantial distortions. There were 29 false statements, of which 8 were in the Guardian, and 6 in bbc tv News, as well as an overwhelming source imbalance, especially on the television news, of around four-to-one against Labour; nearly half the Guardian’s reports had no quoted sources defending the party or its leadership.footnote17 Nor was there any discussion of Corbyn’s documented record of opposing antisemitism as an mp: participating in the Finsbury Park Synagogue vigil, commemorating Holocaust Memorial Day, marking Kristallnacht and the Battle of Cable Street, remembering the victims at Terezín. ‘The idea that Britain’s leading anti-racist is the key problem the Jewish community face is an absurdity’, wrote Joseph Finlay, a former editor at the Jewish Chronicle. Even John Bercow, the bullying Commons Speaker, has testified that having known Corbyn for over two decades, he has ‘never detected a whiff of antisemitism about him’.footnote18

Traditionally, antisemitism in Britain was part and parcel of its Christian culture. What is its prevalence—and in what forms—in today’s secularized, multi-ethnic society? Daniel Staetsky’s fine-grained report, Antisemitism in Contemporary Britain, based on the broadest polling to date, emphasizes that levels of antisemitism in the country are among the lowest in the world; Jewish people are viewed positively by an overwhelming majority of the population. While 40 per cent of Britons have a ‘negative impression’ of Muslims, the figure falls to 7 per cent for Jews—lower than the 10 per cent found in Norway, France and Finland. Jews in Britain run very low risks of being threatened with violence—1 per cent, compared to 7 per cent for ‘immigrants’. The proportion of Britons professing hard-line, ‘learned’ antisemitism, as Staetsky calls it—that is, ‘strong, sophisticated ideas combined with open dislike’—he estimates at 2.4 per cent, with another 3 per cent taking a ‘softer’ version of this position.footnote19 However, as Staetsky points out, since antisemitic signifiers remain part of the culture, a larger number—perhaps 15–30 per cent—may hold one or more stereotypical idea about Jewish people, without being consciously hostile or prejudiced towards them, and perhaps while holding positive ideas as well.footnote20 ‘Most Jews in Britain don’t come into contact with strongly antisemitic ideas’, Staetsky concludes. Due to the diffusion of stereotypes, however, they may well encounter people who ‘from time to time, vocalize views that may make them feel uncomfortable’. As Jamie Stern-Weiner and Alan Maddison argue, however, the regurgitation of stereotypes, whether ethnic, religious or gendered, should be met in the first instance with education and arguments, rather than sanctions.footnote21

Antony Lerman, former founder-director of the Institute for Jewish Policy Research, has suggested that the antisemitism controversy in fact involved a battle between British Jews about ‘the rights and wrongs of the Israel–Palestine conflict’.footnote22 But for the establishment media, only one side mattered. Jewish Labour Party members sympathetic to Corbyn consistently complained about the way the media treated the conservative Board of Deputies—‘mostly Tories and Netanyahu supporters’—‘as if they speak for all uk Jews’: ‘this is definitely not the case; they certainly don’t speak for me.’footnote23 Secular Jewish intellectuals have played a central role in London’s post-war culture, yet the dissenters struggled to get a hearing. The Guardian refused to publish a letter signed by 205 Jewish women challenging the unevidenced allegations levelled against Corbyn by Margaret Hodge mp.footnote24 The London Review of Books was once known for its independent-mindedness on these questions, publishing Edward Said on the Oslo Accords and much good writing from the Israeli left. Generally hostile towards Corbyn—‘This lot or that lot’ was its disdainful comment on the crucial December 2019 election—it barred its doors to dissenting Jewish opinion after one early piece by Stephen Sedley. The paper’s writers—Sedley himself, Jacqueline Rose, Antony Lerman, Avi Shlaim, Donald Sassoon—had to register their opposition to the anti-Corbyn campaign elsewhere.footnote25

Criticisms can certainly be made of the Labour leadership’s handling of the issue. It took nearly four years for the Leader’s Office to get control of the party bureaucracy, which under Iain McNicol had deliberately delayed inquiry into the social-media evidence. Once Jenny Formby took over in 2018, it became clear that the bulk of the haul did not involve Labour Party members at all. The truly disgusting tweets attacking Luciana Berger largely emanated from a hard-right troll, now serving time in prison. The reliance of Corbyn and his aides on the wavering Jon Lansman’s advice, and the notion that they could broker a deal with the Board of Deputies, in trade-union fashion, were mistakes born of labourist ideology. But given the scale and toxicity of the establishment onslaught, besides which the concoction of the Zinoviev Letter in 1924 appears the work of amateurs, the first duty is to salute the moral integrity of Corbyn and his courageous Jewish allies.

Trapped

The media’s antisemitism campaign represented a damaging assault on Corbyn’s Labour from above. Brexit hurt the party from below—dividing it from an important section of its historic voter base. Ironically, the antiquarian nature of the Westminster constituency system—barely altered since the 1980s, despite the population drain to the south—gave greater weight in parliamentary-seats-per-capita to the decimated, small-town north: many southern constituencies had electoral rolls of over 80,000, whereas dozens of northern seats had fewer than 64,000; in addition, the first-past-the-post model brooked no representation for minority votes. As a result, the 52:48 pro-Leave split in the referendum mapped onto something closer to a two-thirds pro-Leave vote in terms of the 650 parliamentary seats. This had a particularly perverse outcome for Labour. Two-thirds of Labour voters were pro-Remain, as were the vast majority of its mps. Yet nearly two-thirds of Labour seats had Leave majorities.footnote26

This disparity would pose an acute problem for Labour in any election polarized around the question of Europe. But for the first twenty months after the referendum, Brexit was neutralized by the prevailing consensus; the Commons voted to trigger Article 50 by a majority of 498 to 114 in March 2017. The next watershed was the June 2017 election, called by May to strengthen her position in Parliament ahead of the Brexit negotiations—another misjudgement of the popular mood. Corbyn’s unexpected success in 2017, winning 30 seats on a 10-point swing, deprived the government of its Commons majority. This in turn opened up a new, parliamentary dimension of the crisis. The erg mps—ultra-Brexiteers on the right of the Tory Party—flexed their muscles in the summer of 2018, when May’s first draft deal proved too eu-ish for their liking. The prospect of defeat for May galvanized the Remain camp, led by the Labour right—Alastair Campbell, Peter Mandelson, Chuka Umunna, Sadiq Khan—with many footsoldiers in Momentum, behind the demand for a second referendum to cancel Brexit. Not only Corbyn’s enemies but his friends were pressing him in this direction: John McDonnell, his Shadow Chancellor, and Diane Abbott, Shadow Home Secretary. This set the scene for the many-sided battle in the Commons that ensued in 2019, with May struggling to pass her Withdrawal Agreement against opposition from her party’s left and right, the Ulster-unionist dup determined to block a deal that had been designed to appease it, Corbyn calling for a new election, Shadow Brexit Secretary Keir Starmer demanding a second referendum, northern mps warning of a coming Armageddon, and the Labour right plotting to overthrow both Corbyn and the Prime Minister and install a self-proclaimed national-emergency government.

The upshot was to force Corbyn’s Labour into a functionally conservative position. Instead of proposing an alternative solution to the crisis, as in 2017, Labour was the main force blocking the implementation of the popular vote, in a defence of the status quo—aligned with the Supreme Court, the House of Lords, the ‘Remainer elite’. The fine accounts by young Labour volunteers in the swathe of northern and midlands seats that fell to the Tories in December 2019—Dudley, Bolsover, Dewsbury, Burnley, Darlington, Barrow and Furness, Blyth Valley—constitute a latter-day Mass Observation on the state of the country. A canvasser criss-crossing the northwest described Brexit as, without doubt, the most common source of voter frustration:

“For Leave voters, Brexit now symbolizes the way in which their voices were being ignored, repeatedly and undemocratically, by the losing Remainers, who are also associated with other classes and more privileged groups . . . As far as they are concerned, Labour (and others) did not fully respect the will of the working class, and a democratic result. They feel betrayed”.footnote27

In December 2019, a weakened Corbyn—smeared as a terrorist in the tabloids, as well as an antisemite, and reluctantly calling for another year or more of Brexit debate and a second referendum—lost 60 seats on a swing of –7.8.footnote28 In principle—though not, perhaps, in political fact—Corbyn could have avoided this position by giving Labour mps a free vote on Brexit legislation in 2019, ‘according to their conscience’, as Harold Wilson had done on the divisive 1975 referendum on the uk’s entry into the Common Market. With the ‘northern group’ voting for the bill and two dozen Labour abstentions, Johnson would have been denied the chance to make electoral hay out of the obstruction of Brexit, and the prospect of combating a much weaker Tory administration would have lain ahead at the next election. A Labour government could then have fought for an open immigration policy, or its own recalibration of the eu’s ‘four freedoms’.

By blocking Brexit in Parliament, and thus ensuring it would have to fight an election on this difficult ground, Labour (and the others) allowed Johnson to capture the power of initiative, to present his party as a radical democratic force. The upshot, of course, is to give a new lease of life to the hegemony of the City and the extraverted dynamics of British capital; an ironic culmination to the long decade that opened with the collapse of Lehman Brothers. Yet other aspects of the crisis remain unresolved. A democrat on behalf of England (and Wales), Johnson is an autocrat for Scotland, now firmly bolted on to Anglo-Britain as an unwilling side-car. He has cut Northern Ireland loose, aligning it with the southern Republic in terms of customs controls—a taboo-busting move for an English Conservative. Although there is no clear Northern Irish majority for reunification at present, Brexit has put the question back on the agenda.

Restoration? Not so much. If the uk’s overall class configuration has been affirmed, three new forces can be discerned within it. The first is a renewed left, both within the Labour Party and outside it. Successive cohorts of radical young activists and thinkers have come of age since 2008, in student protests, anti-austerity battles, radical-independence struggles, climate activism, Corbyn’s Labour and the myriad groups around The World Transformed. Labour will not be a credible opposition, in present conditions, if it decides to inhabit a conservative role, aiming to be the representative of yesterday’s establishment. The new left keeps open the prospect of taking the fight to the terrain of the future with bold solutions for inequality, climate change and the international order, as the Corbyn leadership tried to do.

The second new force is an intensely pro-European body of dissident opinion, concentrated in the liberal intelligentsia. It is not clear yet whether this layer will maintain its present critical stance or reconcile itself to the new dispensation. But isolation from power can be a fruitful experience for an intelligentsia, as the example of the 1980s shows. Under Thatcher, and despite her, Britain saw a golden age of tv at bbc2 and Channel 4, the launch of the London Review of Books, the Guardian op-ed pages covering a genuinely wide span of views, a fresh crop of iconoclastic novelists championed by the newly relaunched Granta and by publishing houses briefly flush with money—a far better record than under Blair and Cameron. Is it unreasonable to hope for another such flowering under Johnson?

The third force, the new-Tory northern working class, is still in the making. As early as 2004, the Dutch political scientist Cas Mudde speculated about an emerging electoral cleavage between metropolitan centres and deindustrialized peripheries, comparable to the 19th-century rural-urban and 20th-century capital-labour cleavages that Seymour Lipset and Stein Rokkan had analysed as the structuring divisions of electoral politics in Party Systems and Voter Alignments (1967).footnote29 Since then the divide between ‘international’ centres and ‘national’ peripheries has been seen in many different lights. For Paul Mason, the progressive alliance of the future lies squarely with the ‘internationals’, the young metropolitan professionals of the Remain camp. For Wolfgang Streeck, the national level offers the only effective basis for democratic accountability, for calling the ravening forces of capital to order. Malcolm Bull has suggested instead that both sides, international centres and national peripheries, may be capable of taking on either left or right inflections.footnote30 The 2019 northern working-class Tory vote doesn’t yet represent a new electoral cleavage in the strong, Lipsettian sense—a new party alignment offering a collective identity for the longue durée, as proposed by the pil in Poland, Fidesz in Hungary, fn in France. On their own terms, working-class Johnson voters are Streeckians, aiming to take back democratic control. They lodged a protest vote in 2016 and demanded it be taken seriously three years later. But the overall trend may still be voter volatility—and further protests—rather than long-term realignment.

Johnson, of course, is no Thatcher. Her corner-shop ideology was wrapped around a detailed—and, in its own terms, coherent—Chicago-style economic policy. Johnson’s Cabinet consists of an unstable mix of free-marketeers and interventionists, and his first steps have been stolen from Corbyn’s programme: increased public spending, a higher minimum wage, nationalizing Northern Rail. Tory governments have historically proved better able than Labour to stand up to Washington—Heath refusing airspace to the usaf en route to the 1973 Israeli-Arab war, Major trying to stay out of the Balkans—and Johnson is pressing ahead with Huawei as the uk’s 5g supplier. But in face of a long-predicted world recession, failing to arrive for years now in a global economy unmoored by trillions of qe dollars and zero interest rates, all bets on the uk economy are off.

Published at https://newleftreview.org/issues/II121/articles/susan-watkins-britain-s-decade-of-crisis