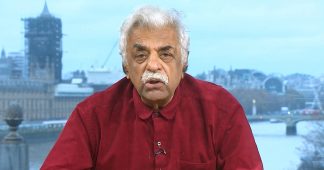

By Radhika Desai

17.12.2019

Boris Johnson’s decisive victory was widely expected to end the uncertainty plaguing British society, politics and economy for some 4 years. The pound rose steeply on the news. However, it fell as steeply, losing more than half its gains the following morning wiping out all gains. What was going on?

There is much to say about the electoral verdict, to be sure. Boris Johnson has done a Trump on Britain. The candidate so many reviled as an untrustworthy bumbler, with a campaign consisting of three little words, ‘Get Brexit Done!’ (like Trump’s ‘Make America Great Again!), has won the biggest Tory majority of recent decades, bigger than Mrs Thatcher’s. The first past the post electoral system gave Johnson an additional 49 seats for winning little more than 1 percent more of the popular vote. The media campaign against the Labour leader, Jeremy Corbyn, plumbed depths of indecency and inaccuracy never before witnessed in the history of electoral politics in Europe, vilifying him for anti-Semitism, unfitness to be Prime Minister, unwilling to use nuclear weapons, befriending terrorists: the list could go on. Nigel Farage sacrificed his Brexit party for the Conservatives when he decided not to run Brexit Party candidates in Tory held seats and confine its role instead to drawing working class votes from Labour in the decaying post-industrial north England rust belt. Transatlantic links emerged with talk of Farage leaving British shores to work on the Trump Campaign. The Liberal Democrats and their brand of professional middle class politics face near extinction. Scottish Independence as well as the re-unification of Ireland have advanced many leagues.

Important as these things are, we leave them for another day. Here we concentrate on the two realizations that sobered markets up and left them with the hangover of the morning after the wild euphoria of the night before.

The first was that Johnson may have won by making the election about Brexit but even Brexit has never been about Brexit. It was always about the Conservatives’ inability to win majorities after 4 decades of punitive and miserly neoliberal austerity politics. Brexit has been the Conservatives’ dangerously clever fix for this problem. Frustrated by his lack of a majority in 2010, Cameron, the remainer, promised a referendum on Brexit in 2015, staking the country’s future for party political gain. The gamble paid off. Cameron got his victory. Expecting, a little self-contradictorily, that remain would win (if it was a vote winner for the Tories, was there not a strong chance that the Brexit position would win in the referendum?), he called the Brexit referendum. In the resulting campaign, Johnson and his mates in the pro-Brexit European Research Group led the leave side. They were convinced less of the wisdom of Brexit than of the centrality of Brexit to the Tories electoral aspects, not to mention to Johnson’s chances of becoming the Conservative leader and Prime Minister. The leave verdict left the country’s political system between the rock of having to deliver on the democratic verdict and the hard place of having to sever economic limbs to do so. That has been the logic of British politics in the past three and a half years since the July 2016.

Although Johnson’s victory has been achieved in good part by promising voters exhausted by the unending and nerve wracking saga of Brexit that he would end it, nothing like that is actually possible, not for a long time. Even if Britain leaves the EU on 31 January 2020 on the ‘deal’ that Johnson has negotiated, a deal which leaves most people and the environment bereft of the superior protections that the EU afforded, the hard work of negotiating the actual terms of the deal will remain. No matter what shape it takes, it is more likely to be merely a new phase in Britain’s relations with the EU, which have always featured a ‘one foot in, one foot out’ stance on Britain’s part. The only bright spots in this outcome is that Johnson’s deal breaks with his own party’s Unionism by envisaging a customs border between Northern Ireland and the rest of the UK. If implemented, it brings the re-unification of Ireland closer and Scottish independence may not be far behind.

The second realization is that the 2o19 election is unlikely to turn out, as was being proclaimed on election night, a watershed election in the way the 1945 Labour Victory and 1979 victory of the Thatcher Conservatives were. The first inaugurated the postwar left-of-Centre Keynesian Welfarist Settlement that dominated the next several decades and the second marked the neoliberal counterrevolution that set the scene of politics for the next many decades. Did the 2019 verdict inaugurate new Johnson/Brexit settlement?

It is true that like in 1945 and 1979, Johnson’s conservatives appear to have changed the electoral geography of Britain radically. Clement Atlee’s Labour Party extended Labour’s reach in 1945, taking seats from the Liberal party in particular. The Thatcher Conservatives famously took the votes of the better off working class, particularly the grateful beneficiaries of her fire sale of publicly owned municipal council houses to their tenants. Boris Johnson’s previously unthinkable inroads into the labour heartland of decaying post-industrial northern England, his breaches in the Red Wall of traditional Labour constituencies has suggested to many that his achievement is similar.

Not so fast. A settlement, as the word implies, has to have settled something, at least for a time. However, Johnson’s victory has settled little and is about to unsettle a lot more. Will Johnson’s Britain will leave the EU on the deal he had negotiated or, will be, knowing that it will only make the job of ruling Britain harder, use his majority to soften in convenient (for him and the Tories, rather than Britain, of course) ways? What new uncertainties will arise form the actual Brexit negotiations that follow? Can Johnson actually afford to settle Brexit and destroy the goose whose golden eggs have become so critical to the Tories electoral chances?

Labour’s victory was a deep, organic development, coming atop of decades of working class mobilization and assertion to reject the miserly and punitive politics of the Conservative-Liberal duopoly of British party politics going back to the late nineteenth century. Such politics became especially stark in the class struggles and Great Depression of the 1920s and 1930s and the Second World War, with its culture of ‘fair shares and equal sacrifices’ dealt the death blow to such politics. While the postwar Keynesian settlement did come undone as contradictions between its social aspirations and its reliance on capitalist growth sharpened, it was lot more stable than its successor.

The 1979 turn to the Conservatives was less deeply rooted, arising only from the contradictions of Keynesian Welfarism. It was inherently unstable, producing too great a number of losers thanks to the unproductive, financialised, credit fuelled and inegalitarian pattern of growth it produced. Nevertheless, through lucky breaks such as the Falklands War and North Sea oil, clever strategies such as the sale of Council houses, and the application of political judgment of how much of her punishing neoliberal agenda it would be electorally safe to impose on Britain, Thatcher managed to win three general elections and her successor, John Major, a fourth. If this was not enough, Tony Blair’s New Labour, by accepting the Thatcherite neoliberal settlement, gave it a longer lease of life. While New Labour was able to extend the life of these arrangements by using the revenues generated by such growth to increase social services rather than reduce taxes, reduced revenues after 2008 closed this option.

Perhaps the most fundamental uncertainty arises because Johnson has won the election by taking constituencies hardest hit by Britain’s industrial decline and the financialized and unequal pattern of growth of recent decades. Joblessness, cuts to services and general hopelessness plague vast areas of England. The Tories’ shrinking electoral fortunes have, since at least the leadership of Cameron, forced them to move to a more centrist position, at least rhetorically. People may remember Mrs May’s speech on becoming PM which spoke of the injustices and hopelessness suffered by so many in the UK today. And, for good measure, Boris Johnson has been referring to himself as a One Nation Tory. The only problem is that there is little in their policies to prove it. Nor is there any sign that this will change. If anything, with Johnson appearing to want to replace Britain’s economic relations with the EU with a new closeness with the US, the direction of their policies can only visit more pain on even wider sections of the British people. This will only make it harder for the Tories to win elections and make them even more reliant on Brexit and, when it has exhausted its electoral potential for them, on some equally wild and disruptive stratagem. Rather than any settlement, Britain is in for a road ahead at least as bumpy, if not more so, as that since the Brexit referendum.