October 5, 2018

The First World War was a contest between two blocs of imperialist powers, whereby a major goal was the acquisition, preservation, and/or aggrandizement of territories – in Europe and worldwide – considered to be of vital importance for the national economy of these powers, mostly because they contained raw materials such as petroleum.

We have seen that this conflict was ultimately won by those powers that were already most richly endowed with such possessions in 1914: the members of the Triple Entente plus the United States. Uncle Sam admittedly became a belligerent only in 1917, but his oil was available from the very start to the Entente and remained beyond the reach of the Germans and Austrian-Hungarians throughout the war because of the British naval blockade.

Let us take a brief look at the role played by Britain in this struggle of imperialist titans.

Britain strode into the twentieth century as the world’s superpower, in control of an immense portfolio of colonial possessions. But that lofty standing depended on the Royal Navy ruling the waves, did it not? And a serious problem arose as the years following the turn of the century witnessed the rapid conversion from coal to petroleum as fuel for ships.

This caused Albion, richly endowed with coal but deprived of oil, to search frantically for plentiful and reliable sources of the “black gold,” of which preciously little was available in its colonies. For the time being, oil had to be purchased from its biggest producer and exporter at the time, the US, a former colony of Britain, increasingly a major commercial and industrial competitor, and traditionally not a friendly power; this dependency was therefore intolerable in the long run.

Some oil became available from Persia, now Iran, but not enough to solve the problem. And so, when rich oil deposits were discovered in the Mosul region of Mesopotamia, a part of the Ottoman Empire that was later to become the state of Iraq, the ruling patriciate in London – exemplified by Churchill – decided that it was imperative to acquire exclusive control over that hitherto unimportant part of the Middle East.

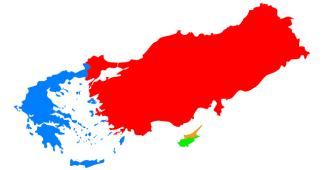

Such a project was not unrealistic, since the Ottoman Empire happened to be a big but very weak nation, from which the  British had earlier been able to snatch sizeable pieces of real estate ad libitum, for example Egypt and Cyprus. But the Ottomans had recently become allies of the Germans, so the planned acquisition of Mesopotamia opened up prospects of war with both these empires.

British had earlier been able to snatch sizeable pieces of real estate ad libitum, for example Egypt and Cyprus. But the Ottomans had recently become allies of the Germans, so the planned acquisition of Mesopotamia opened up prospects of war with both these empires.

Even so, the need for petroleum was so great that military action was planned, to be implemented as soon as possible. The reason for this haste: the Germans and Ottomans had started to construct a railway that was to link Berlin via Istanbul to Baghdad, thus raising the chilling possibility that the oil of Mesopotamia might soon be shipped overland to the Reich for the benefit of a mighty German fleet that already happened to be the Royal Navy’s most dangerous rival. The Baghdad Railway was scheduled to be finished in . . . 1914.

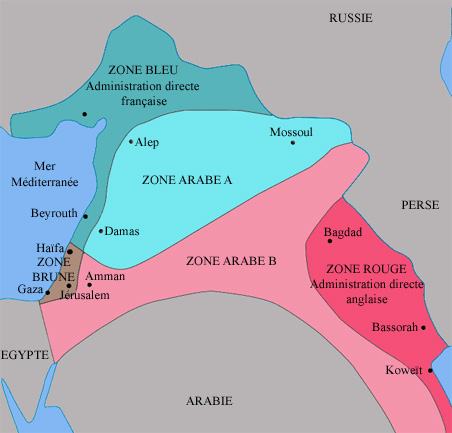

It was in this context that London abandoned its long-standing friendship with Germany and joined the Reich’s two mortal enemies, France and Russia, in the so-called Triple Entente, and that detailed plans for war against Germany were agreed upon with France. The idea was that the massive armies of the French and Russians would crush Germany, while the bulk of the Empire’s armed forces would move from India into Mesopotamia, beat the pantaloons off the Ottomans, and grab the Mesopotamian oil fields; in return, the Royal Navy was to prevent the German fleet from attacking France, and token assistance to French action against the Reich on the continent was to be forthcoming in the shape of the comparatively Lilliputian British Expeditionary Corps. But this Machiavellian arrangement was elaborated in secret and neither Parliament nor the public were informed.

In the months before the outbreak of war, a compromise with Germany was still possible, and was admittedly even favoured by some factions of the British political, industrial, and financial elite. However, such a compromise would have meant allowing Germany a share of Mesopotamia’s oil, while Britain wanted nothing less than a monopoly. And so, in 1914, laying hands on the rich oil fields of Mesopotamia was really London’s real, though unspoken, or “latent,” war aim. When the war erupted, pitting Germany and its Austrian-Hungarian ally against the Franco-Russian duo as well as Serbia, there seemed to be no obvious reason for Britain to become involved. The government faced a painful dilemma: it was honour-bound to side with France but would then have to reveal that binding promises of such assistance had been made in secret.

Fortunately, the Reich violated the neutrality of Belgium and thus provided London with a perfect pretext for going to war. In reality, the British leaders did not give a fig about the fate of Belgium, at least as long as the Germans did not intend to acquire the great seaport of Antwerp, referred to by Napoleon as “a pistol aimed at the heart of England”; and during the war, Britain herself would violate the neutrality of a number of countries, e.g. China, Greece, and Persia.

Like all plans made in preparation for what was to become “the Great War,” the scenario concocted in London failed to unfold as anticipated: the French and Russians did not manage to crush the Teutonic host, so the British had to send many more troops to the continent – and suffer much greater losses – than planned; and in the distant Middle East, the Ottoman army – expertly assisted by German officers – unexpectedly proved to be a tough nut to crack.

In spite of these inconveniences, which caused the death of about three quarters of a million soldiers in the UK alone, all was well in the end: in 1918, the Union Jack fluttered over the oil fields of Mesopotamia. Or rather, almost all was well, because while the Germans had been squeezed out of the region, the British would henceforth have to tolerate the presence there of the Americans, and eventually they would have to settle for the role of junior partner of that new superpower.

* Jacques R. Pauwels is the author of The Great Class War: 1914-1918.