JEAN WYLLYS and FRANCESC BADIA I DALMASES

The upcoming local elections in Brazil are an opportunity to restore democracy and overcome the political crisis. If we do not seize it, Latin America is in for more than a decade of darkness, warns Jean Wyllys

Francesc Badia: Mr. Wyllys, thank you for offering your time to democraciaAbierta. Brazil is facing a deep, threefold crisis: an economic crisis, a social crisis and a political crisis. Which of the three do you think is more decisive?

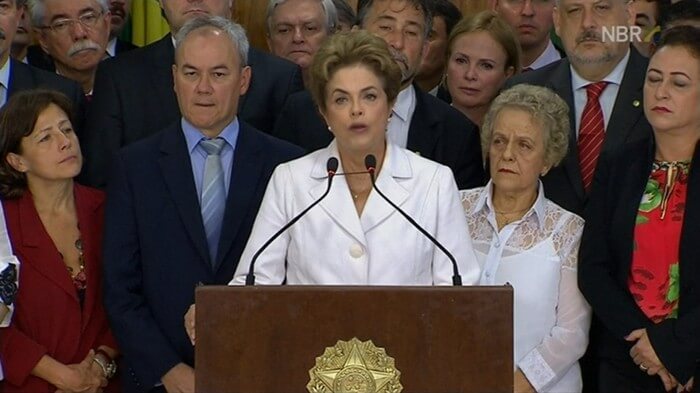

Jean Wyllys: We are coming out of a global crisis, an economic and financial crisis that hit not only developed countries but also developing countries. Everyone felt the impact, but in Brazil our plutocracy and our oligarchs used the economic crisis to promote a political crisis, a destabilization of the duly elected government. This political crisis, which originated within the political system itself, from a dispute between parties and coalitions, got worse as it was transferred, through biased and partisan information, to Brazilian society, especially the middle class, thus giving it a social character. So, the economic crisis split into a political crisis, which in turn split into a social crisis, resulting in a parliamentary coup under the guise of an impeachment that hit President Dilma Rousseff. The president was then removed from office by Congress, first by the House of Representatives and now by the Senate.

President Dilma Rousseff was, from the very first day of her current mandate, sabotaged in the National Congress by Eduardo Cunha, who was elected president of the Chamber of Deputies. It was Eduardo Cunha who prevented Dilma’s government from getting any bills passed, and he is also responsible for accepting the impeachment demand promoted by the opposing Brazilian Social Democracy Party (PSDB) – the party that has lost the last four elections. The PSDB, together with Cunha the corrupt, concocted a coup to depose the elected president. Today we can say, therefore, that all three crises have the same dimension.

FB: Apparently, the only way out of this situation would be to call for a new presidential election. But, according to several analyses, the political system is thought to be exhausted, or, at least, captured by a number of interests that profit from the political fragmentation and the existence of multiple groups that promote internal matters and private interests and thus lose sight of the common interest. Is there a real political will to reform and to overcome this deadlock that is fragmenting the Brazilian electoral system?

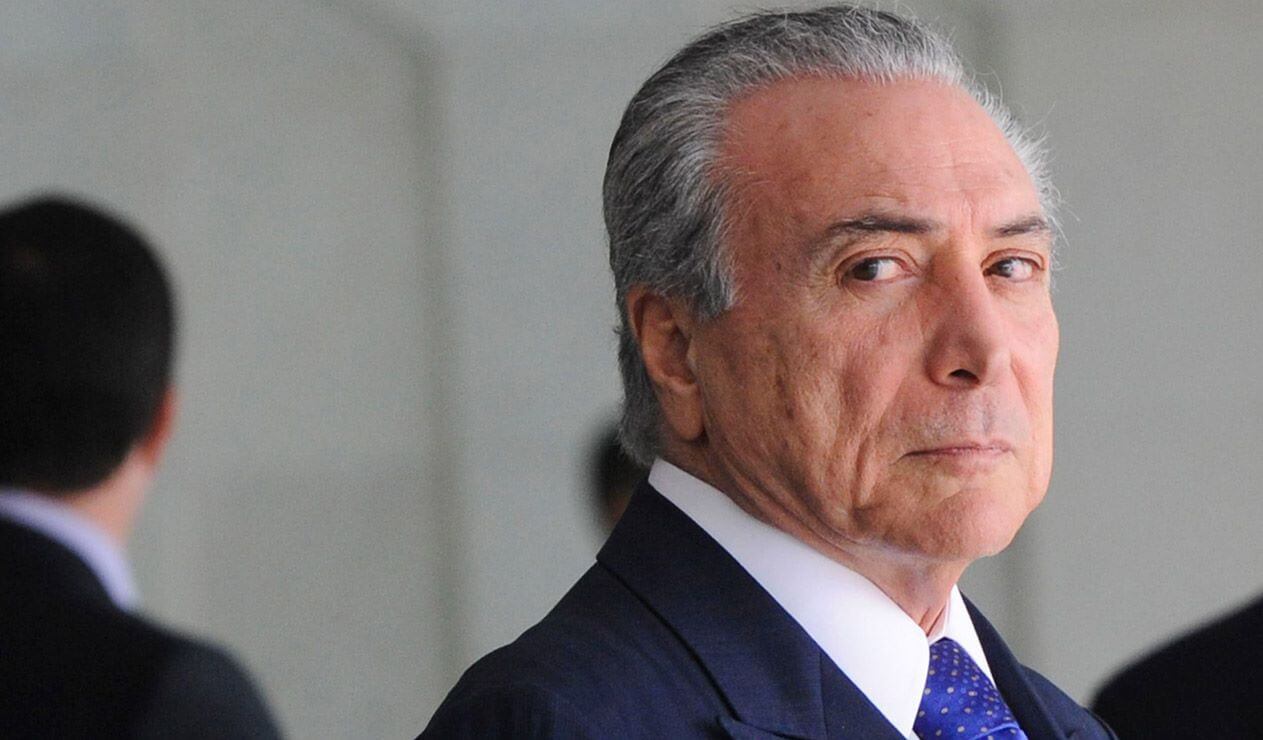

JW: This will exists on the part of the Brazilian population which is demanding new general elections. In the face of this political crisis, citizens want to be heard. What happens is that the Brazilian political system, including the electoral system, is controlled by a network of corrupt politicians who have deposed the elected president. The current government’s approval rating is only 6%. And only 3% of Brazilians know who the current interim president of Brazil is. We are being governed by a person whom the country does not know. A person most Brazilians do not approve of. Nonetheless, the Supreme Court is not intervening, and thus is allowing the situation to persist. So, we live with a government we do not know, a government that we do not approve of, which is applying anti-popular measures. Most of the measures adopted by the interim government, some of them already implemented, are aimed at dismantling the welfare state that has been built over the last 13 years. The holding of elections depends on the radicalization of the social movements, on their promoting general strikes and road blocks. If this popular pressure does not happen, there will be no elections, and we will run the risk of having this government and the Chamber of Deputies replace presidentialism with parliamentarism, and thus Brazilian citizens will lose the right to elect their head of state.

FB: There is a third issue here: social protests and demonstrations. This was an issue that received a lot of attention and has been very much present in recent years, especially since the protests of June 2013. But lately, particularly this year, protests have been manipulated by political parties, and citizens have not been able to express themselves spontaneously and naturally. Many consider that this external polarization has meant that the legitimacy of some of these protests, which perhaps in 2013 represented the voice of the majority, have been fragmented. What do you think of the evolution of the protests and how do you reconcile your call for mobilization with the currently divided and polarized scenario?

JW: The June 2013 protests originated from the social movements on the left and their demands. Four movements gave rise to the protests of June 2013: the Sao Paulo Passe-Livre movement, the movement for reducing rates in Porto Alegre, the movement for the preservation of the “Maracaná Village” and the protests against the World Cup in Rio de Janeiro, and the Fuera Feliciano movement, the LGBT community movement. These four proposals, which made their way from the social networks to the streets, are at the root of the mass protests of June 2013.

At first, most of the media positioned themselves against the protests, using epithets such as “drunkards” and “bandits” to describe the protesters. When the opposition parties and the media realized that the demonstrations were destabilizing Dilma Rousseff’s government, they changed their minds and began to encourage the protests, calling on citizens to go out in the streets, and turning the protests of June 2013 into a mixture of leftist voices and those of fascist right-wingers who saw them as an opportunity. The protests of June 2013 became an amalgam and the media used them to destabilize the government. The protests ushered in the first attack against the government.

When the 2014 elections came, the media had already assembled an army of journalists and columnists to carry out the destabilization work, associating corruption – which in Brazil is systemic, structural and historical – with the Workers’ Party and Dilma Rousseff’s government. This mobilized the middle class against the government and promoted the patriotic protests, all green and yellow, and the calls for a return of the military dictatorship – and for putting an end to the social programs and the anti-racist policies. All of this was supported by the media.

On April 17 this year, when the impeachment process began, the country was able to witness for the first time a live session of the Chamber of Deputies, and listen to the reasons that the representatives were giving for impeaching the president. The country could not believe what it was seeing. Even people who had dressed in green and yellow were amazed by the show, and did not feel in any way represented by these congressmen and congresswomen.

Then the Chamber of Deputies, together with the Senate, managed to take power away from Dilma. This has led us to a situation where the streets are no longer invaded by an ignorant and politically illiterate middle class – who through manipulation by the press believe that the problem boils down to corruption – but rather by leftist social movements that want to preserve democracy and are carrying out the occupation of schools and public spaces in protest against the interim government.

And then came the Olympics, and the protests multiplied. The interim government began to use the national security force and the police against demonstrators. The protests, previously influenced by the media in alliance with the opposition, are now being suppressed by the government that has replaced the deposed president.

FB: You have already mentioned one of the topics I wanted to discuss with you: the role of the media. But there is a very interesting aspect I would like to bring up: at democraciaAbierta and other media we acknowledge the existence of a vibrant civil society, a very dynamic activism which is trying, throughout the region, and in Brazil in particular, to reinvent democracy, especially through young people, women groups, feminists, minority movements, the LGBT movement, and others. We see that there is a will and a capacity for political innovation, including cross-cutting activist platforms aiming at starting a movement from below, from municipalism, possibly inspired by movements such as Podemos in Spain and the like. What do you think of these attempts at political regeneration from activism and activist innovation?

JW: I am part of this movement. I represent the political reaction, or the political will, to democratise democracy. Social movements, in an articulated and cross-cutting way, seek to preserve our democracy and introduce a new management and political representation model – one that corresponds to a high-intensity democracy, a democracy that brings together representative democracy and participatory democracy. While they perform this function of resisting and putting forward these alternatives in areas of urban mobility, public safety, cultural management, city occupation, I continue represent their interests here in Parliament.

I am the only one of the five hundred thirteen representatives with a social mandate who is working from a social council formed by people from different sectors of society. As such, I am accountable to it, and the council is actively involved in the study and analysis of the legislative hypothesis I put forward. We are building a movement for the regeneration of Brazilian politics. Brazil has always been a country where power has been concentrated in the hands of the political oligarchy and the plutocracy. Here a government of the rich has always prevailed. But there has been a relative transformation in recent years, which was promoted by the Workers’ Party (PT) governments and their public policies. Access to higher education, income transfer policies that reduced material poverty and its associated miseries. Racial issues gained enormous relevance and so did gender issues, including the rights of women, the LGBT community and indigenous communities.

In the last 13 years, different social actors have managed to assemble themselves and today we are now a resistance movement. Not on behalf of the PT, but in the name of democracy. We believe that our democracy is threatened, that by removing Dilma Rousseff from office the rules of the democratic game have been broken, and that both Brazil and Latin America are now facing a new form of “dictatorship”, the neoliberal market dictatorship, which aims at destroying the welfare state and at managing poverty through police repression.

FB: We are nearing the end of this interview. I would like to revisit the issue of the scenarios that were constructed by the Alerta Democrática project. These scenarios were very well constructed, and the most negative ones do not seem to be materializing, indicating that democracy has enough resistance capacity in Latin America and Brazil to overcome the pendulum dynamics to the right, towards neoliberalism. This is not happening for the first time, nor is it the first time that it is corrected. What lessons are to be learnt from this phase? What are the prospects for the future? Are there reasons for optimism? Or are we facing a new, long, crossing of the desert?

JW: I will only be able to make a concrete forecast after the municipal elections in October/November. After the mayoral elections in more than 5.000 Brazilian municipalities I will be able to say for sure what awaits us. At the moment, I can see a light at the end of the tunnel if only we can get progressive mayors elected, more qualified and less partisan chambers, and less corrupt councillors, less connected to organized crime. If we elect councillors who are more committed to the interests of the people and democracy, I will be able to say that there will be a clear light at the end of the tunnel and that we will be able to change this scenario in 2018, at the next presidential elections.

But if this does not happen, if the result of the municipal elections is similar to the previous elections (the election of the state governments and the presidency) then, unfortunately, we will be facing more than a decade of darkness in Latin America. A different kind of dictatorship. Not a military dictatorship, but a dictatorship masquerading as being legal, wrapped in false respectability. A market dictatorship, the dictatorship of large corporations. A system where collective rights, minority rights, environmental protection, clean energy and more sustainable ways of life are all declining. A system where, at the same time, xenophobia, racism and homophobia are expanding. In short, all the evils that democracy aims to eradicate or at least control, may resurface with force – as if Pandora’s Box were being opened in front of us.

Today, in Brazil, I would say that the four scenarios projected by Alerta Democrática coexist: a democracy in mobilization, a democracy in tension, a democracy in transformation, and a democracy in agony. The latter scenario is by far the most important one at this time, particularly where state institutions are being captured by organized crime.

FB: Let us hope that after the catharsis of the Olympics, and through strong mobilization in the forthcoming municipal elections, the situation will evolve towards more positive scenarios. We will keep on working to help ensure that democracy does not falter in Brazil. Thank you so much, Jean.