By

Commenting on his EU referendum pledge in 2013 and the referendum on Scottish independence, British prime minister David Cameron claimed in 2014 that he would win the latter easily and put to bed the Scottish question for 20 years, and that the same would go for Europe. From the start, the referendum on Britain’s membership of the European Union was a political gamble to appease the euro sceptic Tory right and to curb the rise of the right wing populist UKIP, which reached a peak in the months prior to the 2015 UK General Election. The victory of the No campaign on Scottish independence and Cameron’s success at the General Election seemed to prove his strategy right.

The deal that Cameron finally reached with the EU on staying in offered greater guarantees of the City’s status as the euro-zone’s offshore financial centre, allowed EU migrants initially to be denied welfare benefits and put a special focus on liberalisation and ‘strengthening competitiveness’. So for Britain to remain a member of the EU would have meant even less ‘social Europe’ – a deal that content wise could hardly be supported even by the mildest social democrat. From a leftist perspective, this EU-deal versus Brexit as propagated by the Tory right and UKIP offered only a cynical choice between a rock and a hard place.

The British left acted divided on this referendum. Labour, Greens, the trade union umbrella TUC and the more radical network “Another Europe is Possible” campaigned for Remain. Though some of those components critically addressed the EU’s democratic deficit and austerity policies, they claimed that EU membership would safeguard the minimal protections for workers provided by existing EU legislation, which a victorious right-wing would dismantle if Brexit gained the upper hand. ‘Remain in and reform the EU’ was their central message.

Some small leftist-led trade unions (ASLEF, BFAWU and the RMT) and radical-left groups such as the SWP promoted Brexit for ‘principled socialist reasons’, based on a class struggle perspective and on enhancing democracy and popular sovereignty. These forces carefully marked their distance from the official Leave campaign led by Boris Johnson and the like.

It is doubtful that the small radical left campaigning for Leave had much of an influence on the outcome of the referendum. The Remain campaign on the other hand was dominated by big business arguments and spreading fear about the economic effects of Brexit. Interestingly, in the final phase of the campaign Labour politicians such as deputy leader Tom Watson, shadow chancellor John McDonnell, and also the general secretary Len McCluskey of the trade union Unite came out for restricting the free movement of labour within the EU, which is part of EU-legislation on workers rights otherwise so dear to the ‘remain and reform’ approach.

A rejection of globalisation

The result of the referendum depicts a deeply divided country: majorities in Scotland, Northern Ireland and the greater London area voting for Remain, all the rest for Leave. With 52 percent overall for Leave, Brexit will become reality.

According to an analysis of voting patterns in the referendum by the think-tank Resolution Foundation, the strongest support for Brexit occurred in those parts of Britain that had been poor for a long time. The result thus reflects an underlying structure of deeply entrenched national geographical inequality. In particular the north and north-east of England, and also Wales – which were the heartlands of Labour – voted Leave. Labour and the TUC urging workers to come out for Remain fell on deaf ears there.

Hence, quite a number of commentators interpret Brexit as a ‘rejection of globalisation’ (Larry Elliot). Concerning the poorer layers of society, it was an expression of protest against an economic system that doesn’t work for them, against the effects of austerity and neo-liberal ‘structural reforms’, with the EU being the symbolic incarnation of all those woes. In my view, this is a key point of any meaningful analysis of what happened.

Is Brexit therefore a ‘victory for the working class’, as some on the left have argued? For this to be so, rejection of a neo-liberal EU would have to been linked to a positive, emancipatory project: e.g. “on building a new Britain, one of workers’ rights, a genuine living wage, public ownership, industrial activism and tax justice” etc., as Owen Jones put it in his 2015 plea for a ‘Left Exit’.[1] That doesn’t seem to be the case. Many voters expressed discontent and frustration with the economic and political elites, but as such this was first and foremost a negative response based on otherwise contradictory motivations.

Immigration and national sovereignty as central campaign issues

The official Leave campaign dominated by the Tory right and UKIP framed the referendum debate clearly around immigration as one major pillar. Alex Callinicos put it right in my view: “The inroads that UKIP has made into the electoral bases of both major parties have pulled the debate on immigration rightwards, but they also galvanised the Tories into trying to recapture control of the European agenda.”[2] Remember the wildcat strikes only some years ago in northern England, raising slogans such as ‘British jobs for British workers’, directed against companies employing posted workers etc. from other EU member states? This is the stuff on which UKIP increasingly attracted a working class electorate that felt abandoned by Blair’s New Labour.

Lord Ashcroft’s referendum-day poll found that 33 percent of Leave voters explained their respective choice that Brexit “offered the best chance for the UK to regain control over immigration and its own borders.” So that is the impact of the right-wing Brexit-campaign, and it cannot be neglected. Behind this are the combined effects of the hollowing out of the EU-Directive on the posting of workers (triggered by ECJ judgments that posted workers are only entitled to the minimum wage of their home country), the impacts of the EU Services Directive (free movement of services, also meaning increased competition via ‘self-employment’ and ‘mini-firms’; strongly promoted by the major UK parties, but also accepted by a grand coalition of Conservatives, Social Democrats and Liberals in the European Parliament) and the abuse of free movement of labour within the EU.

It should be remembered that Tories and New Labour alike strongly promoted ‘Eastern Enlargement’ of the EU with a view to make labour markets more flexible and labour power at home ever more cheaper. Together with Sweden and Ireland, the UK was among the EU countries that opened up its labour markets for eastern European regular and posted workers early after the 2004 enlargement and the consecutive 2007 enlargement concerning Rumania and Bulgaria. Later on, especially Rumanian and Bulgarian workers were targeted by both wings of the Tories, UKIP and New Labour politicians alike as the culprits for creating ‘disorder’ in the UK labour market. In the first quarter of 2016, 2.1 million workers from other EU member states were active in the UK – the great bulk of them coming from Eastern Europe. But there was also an increasing influx from southern European ‘crisis countries’ such as Greece, Portugal and Spain. As an effect of both the EU Services Directive and the 2007/2009 ‘Great Recession’, quite a number of formerly statutory or posted workers from Eastern Europe staying in the UK turned to ‘self employment’ , which was often bogus self-employment.

All this lead to a situation of increased competition in the low-income sector for jobs and income opportunities, triggering a further downward spiral on the already impoverished sectors of British society. Hence the frustration of the indigenous working class and the dynamics of the debate on ‘controlling and capping immigration’ pushed by the political right, to which even the Labour and mainstream trade union side have been ready to make concessions. Some of the Labour and trade union side rightly complain about the thinning out of labour inspectorates, lack of controls that at least the UK minimum wage is paid etc.. But all these ‘deficiencies’ are the heritage of both New Labour and the Conservatives in government. Both showed no serious commitment for applying the principles of ‘equal rights and equal treatment’ of workers which were at least weakly contained in the original EU legislation on free movement of labour and the posting of workers Directive.

It is true that most of those EU and other migrants are active in the metropolitan area around London, which voted for ‘Remain’. In the impoverished areas cited earlier, it was simply the fear of ‘more immigrants coming’ also by white workers and poor that contributed towards tilting the balance to Brexit. This is interpreted as a ‘racist and xenophobic reaction’. This may be so – quite along similar regional patterns known from France, Germany, Austria, Sweden, Denmark, the Netherlands and so on, where the populist right was able to attract broader sections of the working class in exactly such relatively poor (rural or small town) areas where immigration is relatively lower.

In the relatively thriving metropolitan areas, people are used to ‘diversity’ of different kinds, and appear to be more ‘tolerant’. This may be partly so, because middle income households there can afford the cheap services of the ‘self-employed’ Polish plumber, the Romanian gardener etc., and are only too happy to present themselves as open-minded multi-culturalists. That is, there is a hierarchy of labour in place that supposedly benefits both sides, and the middle incomes can get along with this. There also may be a more genuine solidarity between the poor and insecure workers of all ethnic strands, because they understand that they share similar living or working conditions – providing a basis for common actions of resistance. These are often supported by activists coming from the middle strata of society – be it initiatives on defending refugees, the rights of gays and lesbians, and even struggles of precarious workers etc.. However, the ‘disgusting chavs’ are a different issue – the structures of social class and why people move politically in the direction as they do is anathema to many of those ‘best intentioned’ progressive people from the metropolitan middle strata.

According to Lord Ashcroft’s poll, also 49 percent of Leave voters claimed the biggest single reason for their choice was “the principle that decisions about the UK should be taken in the UK”, echoing the slogan of the official Leave campaign on ‘Taking back control’.

‘Taking back control and ‘establishing national sovereignty’ are vague concepts which mean different things to different societal interest groups. For the Tory right and UKIP, recovering sovereignty is a tool for getting rid of the remaining social EU legislation, enabling more financial sector deregulation, closing the borders and continuing with harsher austerity and neo-liberal reforms. Reminding of the British Empire of the ‘good old days’, they promise a bright future for a sovereign UK in a free-market Anglosphere together with the US, Canada, Australia and New Zealand, with a view towards re-invigorating the British Commonwealth. Their ideology – ‘Make Britain Great Again’ – certainly had an impact on the outcome. For the small radical left on the Leave side, taking back control means the opposite of this: ending neo-liberalism, re-building the welfare state, and so on. What many other Leave voters understand by ‘taking back control’, we don’t know.

Blowback

Finally, there is already blowback. The ‘special relationship’ between the EU and the UK as its member is broke. The EU loses one of its economically most potent member states, propelling EU elite fears of further disintegration. Cameron’s referendum gamble to secure a strong Tory government blew up. He will resign as prime minister in October. Had Remain won, he would have been celebrated as a grand strategist by EU elites and the mainstream media – now he is being regarded as a political fool that has been dumped. The Tory government is in a very fragile situation. It will not be easy for the Conservative party to reconcile its feuding factions, to agree on a new leader and a reshuffled cabinet. It will be even more difficult for them to agree on what to propose concretely in the negotiations with the EU (Norwegian model or what else), how to ‘reassure the markets’, and how to square the circle that most MPs in the House of Commons and also British big business are opposed to Brexit. Pressure to hold early elections will most probably rise.

Blowback is also hitting the Labour Party. With more than two thirds of Labour MPs organising a putsch and demanding of Jeremy Corbyn to step down as party leader, there is open civil war between Blairites and the Labour Left. If Corbyn – still supported by the trade unions, Momentum etc. – should win again the leadership contest, there may be a chance for a renewal of the Labour Party, then promoting a strong package of alternative economic and social policies. However, the party may also split if such a scenario materializes. Anyhow, it would entail a very difficult uphill battle for Corbyn to unite two distinct constituencies which are necessary for Labour to beat the Right: the young, metropolitan, university educated and the marginalised, small town, working class; the latter already drifting towards UKIP or abstention. If Corbyn should lose the leadership contest, leftist hopes and the perspective for turning Brexit into a ‘Left Exit’ will most probably be dashed. This would open further political space for UKIP and the like to flourish.

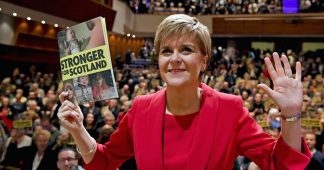

There is possibly more blowback waiting in the wings – the break up of the UK state itself. Debates on reforming the British state have a long history[3], now they seem to come back with a vengeance. The SNP-led Scottish government is lobbying for a second referendum on independence with the aim of an independent Scotland staying within the EU. EU leaders expressed their sympathy for the EU-loyal Scots. However, they will not support Scottish independence, as this would only encourage Catalonian independence from Spain and may be other examples to follow. Sinn Féin and others press for a referendum on Northern Ireland joining the Republic.[4] We will see whether the EU and UK can contain the unfolding of such a dynamic towards break up.

Linked to all this is the question which role the UK can play in the future as regards the alliances of Western imperialist powers with the US at the helm – concerning both the management of global capitalism and western geo-strategy. For the US, the UK was useful as an EU member to provide a channel for influencing the EU and setting agendas. That’s why Obama urged the British to vote for Remain. As a country outside the EU, the UK will be less important for the US, though still for NATO.

After the Brexit vote, the new EU-trio Merkel, Hollande and Renzi emerged to prepare a special EU-Summit on the issue. EU leaders already called to start Brexit negotiations soon, and if the UK would like to stay in the Single Market, it would have to accept free movement of labour as it stands. Furthermore, they announced a ‘period of reflection’ on the future of the EU-27 (as they did after the failure of the ‘EU Constitution’, which was later recycled and pushed through as the ‘Lisbon Treaty’). Will the EU now move towards an ‘ever closer Union’, even a ‘social Europe’? There have always been views among social democrats, Greens and also forces on the left of them claiming that without the UK acting as brake on EU social legislation and federalism, a better European Union would become possible.

In my view, such expectations are mere cuckoo-land. Will Hollande in France revoke the austerity policies already in place and the deregulation of labour law (Loi Khomri) which were pushed through by his government with emergency procedures against a social upheaval of youth and trade unions? Will Renzi in Italy revoke austerity and the Jobs Act that were adopted despite a wave of mass demonstrations and general strikes by trade unions? After Unidos Podemos failed to overtake the Socialists in the recent Spanish elections, and Rajoys PP triumphed again, the first advice of Commission President Juncker to Spain was to install a stable government that carries on with the earlier neo-liberal ‘reforms’ of the conservatives. There is only the Portuguese government left in the EU-27 trying to resist the pressure for more austerity coming from Brussels, Berlin and Frankfurt – such is the current relationship of forces. Anyone with a sense of leftist realism should be able to see that there is no turnaround towards a ‘social Europe’ on offer, but the reinforcement of the neo-liberal iron cage enshrined in the Treaties and EU economic governance.

There will be attempts by Merkel, Hollande and Renzi to circle the wagons, sheltering the EU-27 from the fall out of Brexit and holding the troops together. Nevertheless, centrifugal forces of further disintegration continue to be at work. Moving forward with the Five Presidents Plan to establish an undemocratic fiscal union and a further tightening of the euro-regime (what Schäuble and others want)? Or loosening the integration (what some eastern European members want)? Strong controversies are on the table regarding a partial lifting of sanctions on Russia, with France, Germany, Italy and others in favour, Poland, the Baltics and others against. If the fragile deal with Turkey on the refugee crisis should brake, the old controversies that already led to a partial breakdown of the Dublin and Schengen agreements will resurface. And if stumbling Italian and southern European banks should need new rescue operations, a full blown euro-crisis could reappear. These might be the seeds of the European Union’s self-destruction.

——————————————-

[1] https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2015/jul/14/left-reject-eu-greece-eurosceptic

[2] http://isj.org.uk/brexit-a-world-historic-turn/

[3] See for example Tom Nairn: Farewell Brittania, Break-Up or New Union?, New Left Review 7, January – February 2001

[4] Sinn Féin was a major force in the initial victory of the No-side on the Irish referendum on the Lisbon Treaty. It is somehow ironic that they use the victory of Remain in Northern Ireland to pursue their stated goal of a united Ireland. Anyhow, ‘Give Northern Ireland back to the Irish’, as Paul McCartney sang in the early 1970ies, is entirely correct in my view.

Published at https://lexit-network.org/blowback-brexit-and-its-aftermath