By Dimitris Konstantakopoulos

The murder of the Russian journalist, political scientist and activist Darya Dugina-Platonova, and the planned – according to all indications – murder of her father, Aleksandr Dugin, a philosopher and politician with significant influence on Russian public opinion and the armed forces, on the outskirts of Moscow, in the very heart of Russia, must be considered as an act of terrorism. In particular as it was a political crime targeting two persons not for their actions or their decisions, but for the journalistic work of Darya Dugina and for the ideas expressed by her and her father. That makes this assassination totally reprehensible from the point of view of the so-called “Western civilisation” and those who invoke it on every occasion.

Significantly, the murder was preceded by the inclusion of Darya in US sanctions for “disinformation”. That is, again, not for her actions, but for how she did her journalistic and political work and the ideas she expressed. It is believed that her last report from Donbas enraged Ukrainian nationalists (and, we guess, the special services of the “collective West” behind them).

Insofar as this murder is linked, even indirectly, to the present conflict between the West and Russia, it has no historical precedent, even in the worst moments of the Cold War.

But we have probably something more here: the assassination could represent a major provocation with global significance, scope and potential consequences, by the forces struggling to escalate the war. It comes on top of another continuing provocation around the nuclear power station of Zaporhizie (Who wants a nuclear disaster in Ukraine? The role of the Black International | Defend Democracy Press) and other events. Thus it is another link in a chain of events that could, without us even realising it, bring us closer to World War III, that is, to the destruction of humanity.

Upon reading this, you may characterise the author of these lines as extreme, exaggerated or alarmist. I will remind you that it is not me, but people with much better information than I have who have come to this conclusion about the current world situation, such as Henry Kissinger (“we are on the threshold of the war between America and Russia”), UN Secretary-General Guterres (“we are a miscalculation away from nuclear war”), and Professor Mearsheimer (“we are playing with fire in Ukraine”).

Darya

When I read the news of Darya’s murder on my computer screen on Sunday morning, I could not believe my eyes. The whole story seemed so incredible to me that I would, if I could, call her and ask: “But how has all this happened? Did they really kill you? Who did it?”

Her assassination seemed so incredible to me, because Darya was the embodiment of life, the exact opposite of death. A very dynamic young woman, very smart, very beautiful, very educated and above all a determined, devoted fighter for her ideas – whether one agrees or disagrees with them – and for her country: ideas and a homeland to which she sacrificed her life, so prematurely.

Darya was the only child of a couple of “heretical” Russian intellectuals, who so often in the history of this country have played a catalytic role, expressing historical needs and different versions of its future, especially when Russian society seemed speechless, amorphous and frightened, as it was in the aftermath of the Soviet collapse. She grew up in an environment characterised by the turbulent searches of her father in the spheres of Russian ideas and politics and the very strong personality of both Alexander and his second wife and mother of Darya, the philosopher Natalya Melentyeva. Both her parents were hit by the terrible dialectic of the human tragedy which has now left them inconsolably orphaned by the hand, as everything indicates, of a fanatic Ukrainian nationalist, of the notorious neo-nazi Azov Batallion.

Darya was the best follower of her father’s ideas and gradually grew into their best “ambassador”, both in Russia and internationally, combining journalism and political activity. She gradually began to adopt the name Platonova, which echoed her father’s and her own love for ancient Athens and Greece and, in particular, certain currents of ancient Greek thought, such as Neoplatonism. When I asked her why she did it, she told me that she had had enough, she wanted to be treated as an independent personality, not just as an extension of her father and his ideas. I am certain that she had all the potential needed, if her life had not been cut off so prematurely, to create her own, independent and particular contribution to Russian politics and ideology.

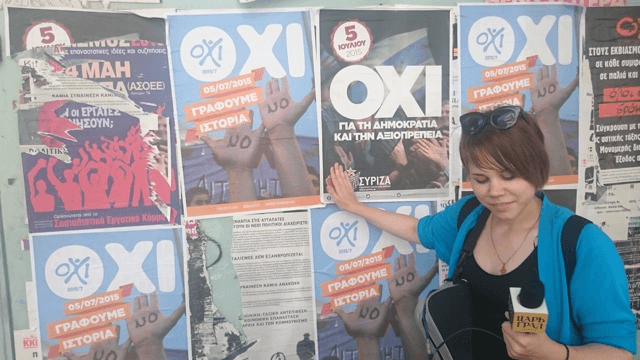

I met her for the first time in 2015, when she was beginning her journalistic career. She came to Greece with a TV crew to cover the Greek/European crisis which was heading for its climax and she asked me to help her with some interviews and the organisation of the reportages she wanted to make.

This was a time when Greece, its struggle against the catastropic programmes imposed on it by Germany, the EU, the IMF and – indirectly – by the US and the international financial capital, as well as the meteoric rise of a party of the “radical left”, SYRIZA, had captured the global imagination. In the Greek struggle were crystallised hopes for a better world economic order. Many people were looking with hope and interest to Greece, from France to Venezuela, from Germany to Russia, from Japan to Black Africa. Everywhere, the Greek crisis was the main topic of discussion. Unfortunately, in Athens itself, there was no one to work on this factor systematically, in order to create an international political atmosphere and the alliances necessary for any negotiation, even more so for a rupture with such strong forces.

I remember how Darya absorbed all information and analysis, with the curiosity that one finds ususally only in young children, in their insistence when they ask you more and more questions, until they have completely clarified in their minds the issue at hand. We were together in Constitution Square of Athens on the day of the referendum, watching the television screens impatiently, until we saw the number, 61,3%, reflecting the triumph of the No (Oxi). And we watched with bewilderment Tsipras appear on TV, not with the expression of a leader who had accomplished a historic triumph, but rather as a man going to a funeral. He was really going to one.

I started this article by referring to the great international political significance of this assassination. In my next article I will refer more extensively to this. I hope to have the opportunity, on another occasion, to also talk about the world of Aleksandr Dugin and his relationship with Greece.