Greece’s harsh social reality

By Yiannis Mouzakis

The key figures reflecting the extent of the economic collapse that Greece has experienced since 2009 are pretty well known, even to those who have not been following the story that closely over the past few years.

The loss of a quarter of economic output and the increase in the unemployment rate close to 28 percent at one point have been widely and repeatedly reported as Greece has struggled through a state of perma-crisis in recent years.

As economic activity fell, jobs were lost, wages were severely cut, taxation kept increasing and disposable incomes were abruptly reduced. Large parts of Greek society felt like the ground under their feet had given way. Living standards were compromised to varying degrees and, as usual, the weakest in society were the most vulnerable to these abrupt changes. Many faced a daily battle to meet basic needs and keep their families afloat. Habits have also been affected by the economic calamity, which has impinged on Greek society in ways that often go unnoticed, unlike the headline numbers.

For instance, according to the Living Conditions publication of ELSTAT, Greeks seem to be much more reluctant to get married: weddings have dropped from a high of 61,377 in 2007 to 53,105 in 2014, when the most recent data is available. In the meantime, civil weddings have doubled from their 2003 level of 13,210 to 26,915 in 2014. The two contrasting trends suggest that financial considerations have played an important part in shaping them.

The last few years have also seen an increase in the number of divorces. The most recent data, from 2013, points to 16,717 divorces, compared to around 13,000 in the preceding years. Although the increase affected marriages of all durations, the most marked rise was in marriages of more than 10 years, where divorces increased from 8,334 in 2009 to 10,091. Obviously, there is a range of factors that can affect the sustainability of marriage, but there is a suggestion that the added financial and social pressures linked to the crisis have taken their toll on some unions.

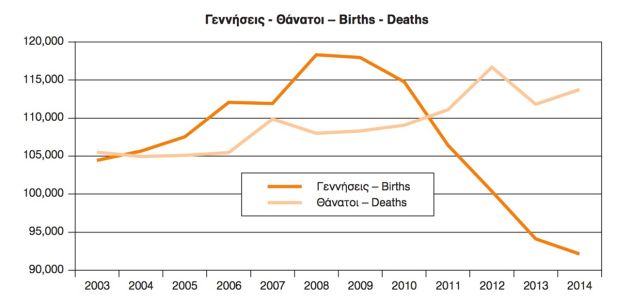

Since the high of 118,302 births in 2008, there has been a significant drop during the crisis. By 2014 the figure had fallen to 92,148. In fact, Greece has had a negative birth rate since 2011. In the absence of migration, the population of Greece would have fallen by 21,592 in 2014.

Greece’s demographic footprint is steadily being reshaped as the crisis rumbles on.

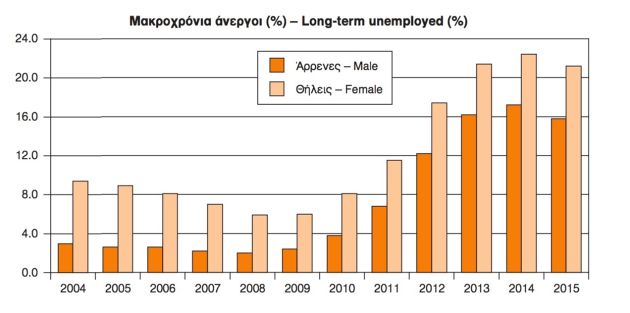

Job and income insecurity have impacted family planning as long-term unemployment in 2015 was 875,259 – equally affecting men and women – and only marginally lower from the 2014 high of 936,832.

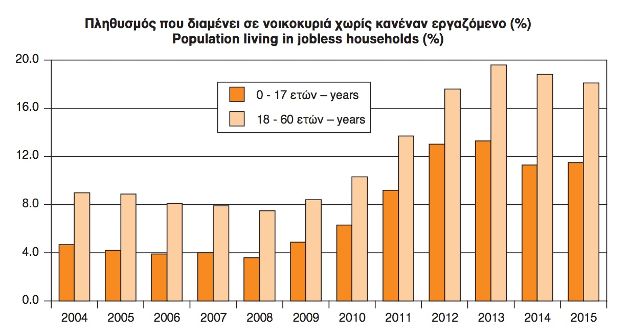

Within the economically active age group of 18 to 60 year olds, 18 percent were living in jobless households in 2015. When children are included in this group, the figure reaches 1,280,745, which means that 12 percent of the entire Greek population does not have an income from employment.

In the same year, more than 1.1 million Greeks were living in low-work intensity homes, where working-age members worked less than 20 percent of their work potential and availability, with a knock-on effect on incomes. In 2009 that figure was much lower at 539,000.

These labour-market developments have pushed parts of Greek society below the poverty threshold, which in 2015 was 4,512 euros of annual income, down from 7,178 in 2010.

More than a third of Greeks (35.7 percent) are currently considered at risk of poverty or social exclusion. The absolute figure stood at 3.8 million in 2015, from about 3 million in the 2007–2009 period. In 2014, when there is comparable data, only Bulgaria and Romania had higher risk-of-poverty rates.

The risk-of-poverty rate is even higher when current income is compared to the poverty threshold set in 2005. When measured that way, the deterioration of living standards is startling as 42.2 percent of Greeks have dropped below the poverty threshold of 2005, from just 16.3 percent in 2010. That amounts to an almost threefold increase in just five years.

From 23 percent in 2009, almost four in ten Greeks are now facing material deprivation in terms of basic standards of respectable living. That is 44.5 percent for children, 41.5 percent for economically active adults and almost 35 percent for over-65 year olds.

The impact of the financial strain on Greek society is multifaceted and so far-reaching that it has been deemed to have directly linked to the quality of people’s health. In 2009 just 4.1 percent of the Greek population were unable to obtain medical examination and treatment. The obstacles in meeting these needs were economic, operational (waiting lists), logistical (not being close to a doctor or hospital) or psychological (fear of being treated) in nature. In 2015, over 14 percent of the Greek population could not obtain the required examination or treatment.

The gravity of the role that economic difficulties have played in the deterioration of health standards is demonstrated by the bottom two quintiles of income, which have seen the percentages of unmet health needs more than double to 19.7 percent for the quintile with the lowest income and treble to 18 percent for the next income quintile.

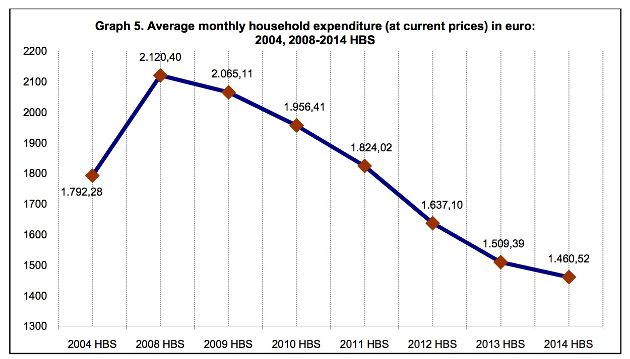

Naturally, spending habits have also changed as lower disposable income required the reallocation of financial resources in types of spending. Households average monthly expenditure, according to the annual Budget Survey published by ELSTAT, is falling continuously since 2009 and in 2014, the latest available year with data, it is 31% lower at 1,461 euros from the 2008 level.

Food, a basic need, now represents more than 20 percent of monthly household expenditure from 17.3 percent in 2009. In spite of a higher budget allocation to food, Greeks dietary habits have taken a turn for the worse. Since 2009, the average monthly consumption of vegetables has fallen by 3.5 kilograms, of fruit by 2.5kg, of meat by 1.6kg and of milk roughly by around 1.3 litres.

Housing expenditure has increased by two percentage points to 13.4 percent. Clothing and footwear has dropped by two percentage points to 5.9 percent of expenditure, durable goods have also lost two percentage points in the household budget allocation, falling to 5 percent of the monthly spend. Hotels, cafes and restaurants dropped by a percentage point to below 10 percent.

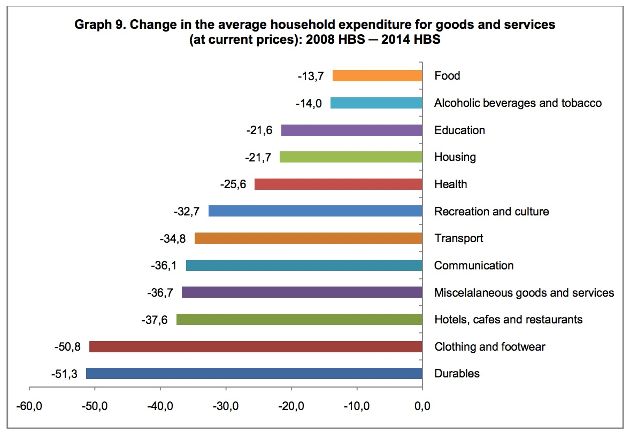

The drop in spending across all categories has been precipitous since 2008, ranging from 13.7 percent on food to circa 51% sharp drop in expenditure on clothes and footwear category and on durables.

Tighter budgets influence residents’ ability to engage in travel and recreation. In 2009, almost 4 million Greeks took a trip of four days of more. In 2013, this figure had fallen to 2.6 million and recovered only marginally to 3 million in 2015. Total personal trips came to over 7.7 million in 2009, but this figure plummeted to 4.3 million last year.

These statistics reflect developments that are life-altering, abrupt and involve deep changes in the standards and quality of life. They are so extensive that they are likely to leave permanent scars.

Economically active men and women might not expect to find themselves in full employment again as their skills erode after years out of work amid an expected slow recovery for the labour market.

Thousands of children that live in households that have no member in work (230,774 in the first quarter of 2016) will not have decent opportunities to develop in physical, educational or professional terms.

These devastating social developments have often been described as a humanitarian crisis, a term so overused by some that it became tired and seemed like a vast exaggeration in the context of the refugee crisis or the Syrian situation. However, war-torn countries and migration on an unprecedented scale should not be the benchmark here.

Greece is a country where statistical figures are thoroughly monitored. This hard data drives political decisions from its lenders. The economic and social deterioration that Greeks are living through is also captured in hard numbers. These statistics should not be neglected any longer.