By James K. Galbraith

The groundwork for the Brexit debacle was laid last July when Europe crushed the last progressive pro-European government the EU is likely to see – the SYRIZA government elected in Greece in January 2015. Most Britons were not directly engaged with the Greek trauma. Many surely looked askance at the Greek leaders. But they must have noticed how Europe talked down to Greece, how it scolded its officials, how it dictated terms and how it made rebellious country into an example, so that no one else would ever be tempted to follow the same path.

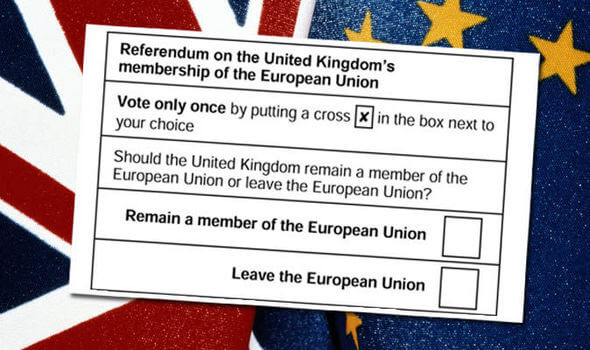

If the destruction of Greece helped set the tone, Leave won by turning the British referendum into an ugly expression of English nativism, feeding on the frustrations of a deeply unequal nation, ironically divided by the very forces of reaction and austerity that will now come fully to power. The political effect has sent a harsh message to Europeans living in Britain, and to the many who would have liked to come. The economic effect will leave Britain in the hands of simpletons who believe that deregulation is the universal source of growth.

That such a campaign could prevail – leading soon to a hard right government in Britain – testifies to the high-handed incompetence of the political, financial, British and European elites. Remain ran a campaign of fear, condescension and bean-counting, as though Britons cared only about the growth rate and the pound. And the Remain leaders seemed to believe that such figures as Barack Obama, George Soros, Christine Lagarde, a list of ten Nobel-prize-winning economists or the research department of the IMF carried weight with the British working class.

Since nothing happens, at first, except the start of negotiations, the immediate economic effects may be small. If the drop in sterling lasts, British exports may actually benefit. If the world gets skittish, the dollar will rise and US exports may suffer, with possible political consequences in America this fall. Otherwise, in the most likely case, the markets will settle down and British life will continue normally at first – except, of course, for immigrants. This will further give the lie to the scare campaign.

Over time, however, as they apply to the United Kingdom, the structures of EU law, regulation, fiscal transfers, open commerce, open borders and human rights built over four decades will now be eroded. Exactly how this will happen – by what process of negotiation, with what retribution from the spurned powers in Brussels and Berlin, by what combination of slow change and abrupt acts, with what consequences for the Union of Scotland to England – is clearly unknown to the leaders of the Leave campaign. This morning they appeared on British television in equal parts triumphant and clueless.

And the crisis now erupts everywhere in Europe: in Holland and France, but also in Spain and Italy, as well as in Germany, Finland and the East. If the hard right can rise in Britain, it can rise anywhere. If Britain can exit, so can anyone; neither the EU nor the Euro is irrevocable. And most likely, since the apocalyptic predictions of economic collapse and “Lehman on steroids” that preceded the Brexit referendum will not come true, such warnings will be even less credible when heard the next time.

The European Union has sowed the wind. It may reap the whirlwind. Unless it moves, and quickly, not merely to assert a hollow “unity” but to deliver a democratic, accountable, and realistic New Deal – or something very much like it – for all Europeans.

James K. Galbraith holds the Lloyd M. Bentsen Jr. Chair in Government/Business Relations and a professorship of Government at the Lyndon B. Johnson School of Public Affairs, The University of Texas at Austin. His new books are Inequality: What Everyone Needs to Know (Oxford, March), and Welcome to the Poisoned Chalice: The Destruction of Greece and the Future of Europe (Yale, June).