In 1801 a British nobleman stripped the Parthenon of many of its sculptures and took them to England. Controversy over their acquisition by the British Museum continues to this day. Was it preservation, or pillage?

By

March/April 2017

During the 1700s, a European Grand Tour was a rite of passage for the sons of wealthy families. Lasting for up to three years, and taking in Switzerland, Paris, and Rome, the high point of this secular pilgrimage for most travelers was Greece. On arriving in Athens, the first sight these young tourists would look for was the Acropolis and its crowning glory: the pillared Parthenon, dedicated to the warrior goddess Athena.

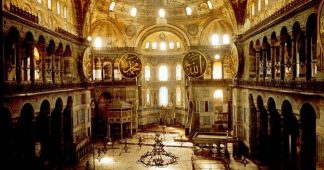

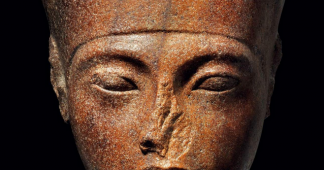

Yet even as the Grand Tour became increasingly popular, laying the foundations for modern tourism, this great monument, studded with the work of the great Athenian sculptor Phidias, was at risk of disappearing entirely. Since the 15th century, Greece had been ruled by the Ottoman Empire, whose troops had converted the Acropolis into a garrison, and whose sultan, Mehmed II, had turned the Parthenon itself into a mosque, complete with a minaret.

In 1687, during a war fought between Venice and the Ottomans, the great monument was used by the Ottomans to store gunpowder. Exposed on the Acropolis, the Parthenon was a highly vulnerable target, and in September that year, a deadly blow fell: A Venetian mortar struck it, causing a colossal explosion that destroyed its roof, leaving only the pediments standing. Later, the Venetian admiral Francesco Morosini tried to remove sculptures in order to take them back to Venice. The pulley he was using broke, and the figures, including a large Poseidon, was smashed to pieces.

Morosini withdrew from Athens with the dubious of honor of having caused more damage to the Parthenon in just one year than it had suffered in the two millennia since Socrates and Pericles had watched its slow rise over Athens at the end of the fifth century B.C.

Parthenon in Peril

By the middle of the 18th century yet more of the ruined Parthenon’s decoration had been plundered. The site’s precariousness only encouraged travelers to carry off items, as many believed it would be razed to the ground before long anyway. “It is to be regretted that so much admirable sculpture as is still extant about this fabric should be all likely to perish … from ignorant contempt and brutal violence” warned Richard Chandler, an English antiquarian, in 1770. A few years later, the Irish painter Edward Dodwell reported that huge quantities of marble from the Parthenon had been broken up in order to build cabins for a garrison. On hearing about the situation, many western travelers and collectors sought to acquire treasures pillaged from the Parthenon on the local black market in an attempt to “save” them from destruction.

Some collectors claimed this was perfectly legal, as they removed items with the connivance of the Ottoman authorities. Many collections of Parthenon statuary housed in the world’s museums today were acquired in this way. The most famous and significant was brought to London beginning in 1803 by the former British ambassador to the Ottoman Empire, the nobleman Thomas Bruce—more commonly known as Lord Elgin.

Taking the Marbles

Thomas Bruce, seventh Earl of Elgin and 11th Earl of Kincardine, was an aristocrat with a promising political career. During the first years of the war with revolutionary France, he held various diplomatic posts in Vienna, Brussels, and Berlin. He returned to his native Scotland in 1796, where he built a splendid country mansion at Broomhall. The architect behind the project was Thomas Harrison, who shared his client’s passion for Greek sculpture and architecture. In 1799 Lord Elgin’s diplomatic services were again required—this time as ambassador to the Ottoman sultan Selim III, who was keen to foster allies from Europe who would help him boost his defenses against Napoleon’s campaign in Egypt, then under indirect Ottoman rule. Having married hastily in September 1799, Elgin set sail from Portsmouth with his new wife, the heiress Mary Nisbet, bound for Constantinople (now Istanbul). Before Elgin left, Harrison urged him to use his privileged position to get hold of drawings and copies of Greece’s great monuments. Lord Elgin agreed and enlisted a team of artists directed by the painter Giovanni Battista Lusieri.

On their arrival, Lord and Lady Elgin were lavishly received by the sultan. While his wife organized sumptuous parties, Lord Elgin sent Lusieri and his team to Athens to sketch ancient works of art, as requested by Harrison. Lusieri was given free rein to carry out his work—except when it came to the Acropolis. In order to gain access to the monument, the Ottomans demanded large daily payments, and they refused to let the painter set up a single piece of scaffolding. Lusieri then asked Lord Elgin to request a firman, a special permission from the sultan himself.

On July 6, 1801, Lord Elgin received authorization, not only to survey and take casts of the sculptures but also to remove whatever pieces were of interest to him—or at least that’s how Elgin interpreted this now controversial passage from the sultan: “When they wish to take away some pieces of stone with old inscriptions and figures, no opposition be made.” Having won the favor of the governor of Athens, Lusieri and his men dismantled a large part of the frieze from the Parthenon as well as numerous capitals and metopes. Finally in 1803, the huge collection of marbles was packed up into about two hundred boxes, which were then loaded onto wagons and transported to the port of Piraeus to await their passage to England.

Read more at https://www.nationalgeographic.com/history/magazine/2017/03-04/parthenon-sculptures-british-museum-controversy/