By Nick Beams

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) has issued its clearest warning yet about the global implications of rising corporate debt in China.It came in the form of an address delivered by David Lipton, its first managing director, at a conference in Shenzhen at the weekend.

The speech came at the end of the review by an IMF team of the Chinese economy and in the wake of data showing overall debt rose to 237 percent of gross domestic product in the first quarter of this year. This was the result of a sharp rise in lending in the last months of 2015 and at the beginning of this year as authorities sought to stabilise the economy following financial turbulence and fears of a sharp drop in growth.

Lipton told the conference that while the levels of government and household debt were not particularly high by international standards—both running at about 40 percent of GDP—corporate debt was a “different matter.” Standing at around 145 percent of GDP it was “very high by any measure.”

“Corporate debt remains a serious and growing problem that must be addressed immediately and with a commitment to serious reforms,” he said.

Turning to the global implications, Lipton continued: “We have learned over and over in the past 20 years how disruptions in one country’s economy and markets can reverberate worldwide.” Those reverberations were evidenced earlier this year in the “spillover” effects from turbulence in Chinese markets.

Lipton said the recent rapid increases in credit meant the debt problem was growing. “This is a key fault-line in the Chinese economy. … And it is important that China tackles it soon.”

In its latest Global Financial Stability report, the IMF estimated that potential losses for the corporate portfolios of the country’s largest banks could be around 7 percent of GPD. But it has acknowledged this is a conservative estimate because it excludes potential problems in the country’s “shadow banking” sector.

Lipton cited the recent remarks by an official, described as an “authoritative person” in the People’s Daily, who spoke of the need to deal with the problems of “zombie firms” and “debt overhang.”

Singling out state-owned enterprises (SOEs) for particular attention as the major source of the debt problem, he noted that by IMF calculations they account for about 55 percent of corporate debt, while contributing 22 percent to economic output and were far less profitable than private enterprises.

“In a setting of slower economic growth, the combination of declining earnings and rising indebtedness is undermining the ability of companies to pay suppliers or service their debts. Banks are holding more and more nonperforming loans … The past year’s credit boom is just extending the problem. Already many SOEs are essentially on life support,” he said.

The risk was that if the problem were not dealt with it could develop into a crisis. “Company debt problems today can become systemic debt problems tomorrow” and “systemic debt problems can lead to much lower economic growth, or a banking crisis. Or both.”

Of particular significance is the fact that while debt is growing it is not bringing the boost to the Chinese economy it once did. In the year to November 2009, total credit increased by an amount equivalent to 34 percent of GDP, boosting the growth rate from 6.1 percent in the first quarter of the year to the full year level of 9.2 percent. In the year to last February, total credit increased by 40 percent of GDP—a larger amount than in 2009 because of the growth of the Chinese economy—but the growth rate has only been barely maintained at just over 6.5 percent.

Three days after Lipton’s remarks, evidence of the problems of lower growth came in the form of data showing investment in China fell to its lowest level in 16 years for the first five months of the year, largely as a result of cutbacks by private companies.

Fixed asset investment expanded by 9.6 percent, the lowest level since 2000, with private sector investment rising by only 3.9 percent, compared to an increase of 23.3 percent in the state-owned sector.

China economist at Capital Economics, Julian Evans-Pritchard, noted: “The continued deceleration of private sector investment means the risk is growing that as policy support wanes, the economy could face another downturn.”

Figures from heavy industries point in this direction. Steel output increased by 2 percent in May but production for the first five months of the year remains below where it was last year. Coal output dropped by more than 17 percent compared to a year ago and output from thermal power stations was down by 6 percent.

In construction and real estate, the Financial Times reported that the housing market is “struggling to work through the ranks of empty apartment blocks in provincial cities and country towns” and property sales “have slowed in recent weeks after sharp rises in the largest and most sought-after cities in the first quarter.”

The significance of the Chinese debt warnings debt and its slowing economy comes more clearly into view when seen in the context of the global economy. The massive expansion of credit in China was a response by government and financial authorities to the global financial crisis of 2008–2009 which saw the loss of more than 20 million jobs. It was predicated on the assumption that growth would resume its previous path in the advanced economies that provide the major markets for Chinese exports.

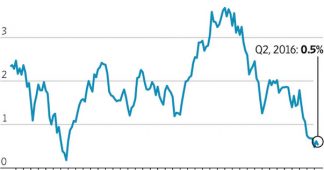

But that has not eventuated. In the US, economic “recovery” after the ending of the “official” recession in 2009 has taken place at the lowest rate of any such phase in the post-war period, while economic output in the euro zone has only recently reached the levels it attained before the financial crisis.

However, the investment boom in China, made possible by the expansion of credit did provide a boost to economies supplying raw materials to Chinese industry. This gave rise to the conception that the so-called BRICS economies—Brazil, China, India, Russia and South Africa—could provide a new base of stability for global capitalism.

Even a brief survey of these economies shows this was an illusion. China is experiencing low growth and rising debt problems.

In Brazil, GDP contracted at an annual rate of 5.4 percent in the first quarter, following a 5.9 percent drop in the final three months of 2015. The Russian economy, hit by falling oil prices and sanctions, shrank by 3.7 percent in 2015, with warnings of further contractions to come or at best stagnation. In India exports have fallen for the past 17 months, the official growth rate of 8 percent is widely regarded as not believable and there are concerns about “stress” in the country’s banking system. South Africa’s economy contracted by 1.2 percent in the first three months of 2016, due to declining output in the mining sector and the impact of a drought, raising fears it will experience a recession for the year as a whole.

The rising debt problems in China and the contractions in major economies that have depended on it are particular expressions of the basic trend in the global economy towards stagnation and slump.