by Conn Hallinan

On one level, the recent financial agreement between the European Union (EU) and Greece makes no sense: not a single major economist thinks the $96 billion loan will allow Athens to repay its debts, or to get the economy moving anywhere but downwards. It is what former Greek Economic Minister Yanis Varoufakis called a “suicide” pact, with a strong emphasis on humiliating the leftwing Syriza government.

Why construct a pact that everyone knows will fail?

On the Left, the interpretation is that the agreement is a conscious act of vengeance by the “Troika”—the European Central Bank, the European Commission and the International Monetary Fund—to punish Greece for daring to challenge the austerity program that has devastated the economy and impoverished its people. The evidence for this explanation is certainly persuasive. The more the Greeks tried to negotiate a compromise with the EU, the worse the deal got. The final agreement was the most punitive of all. The message was clear: rattle the gates of Heaven at your own peril.

It was certainly a grim warning to other countries with strong anti-austerity movements, in particular Portugal, Spain and Ireland.

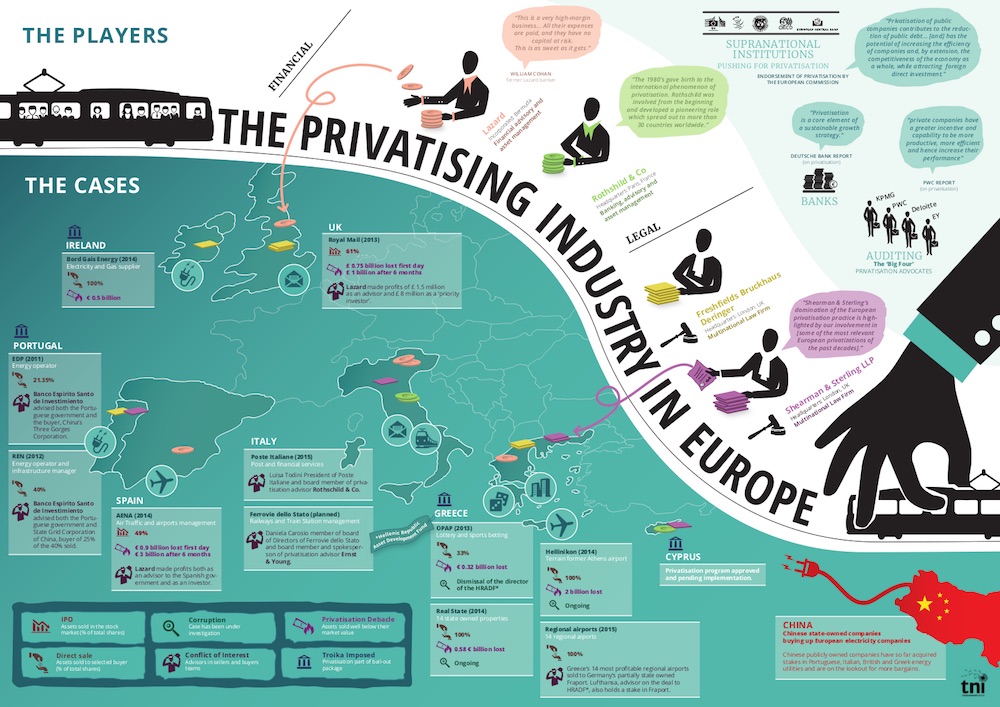

But austerity as an economic strategy is about more than just throwing a scare into countries that, exhausted by years of cutbacks and high unemployment, are thinking of changing course. It is also about laying the groundwork for the triumph of multinational corporate capitalism and undermining the social contract between labor and capital that has characterized much of Europe for the past two generations.

It is a new kind of barbarism, one that sacks countries with fine print.

Take Greece’s pharmacy law that the Troika has targeted for elimination in the name of “reform.” Current rules require that drug stores be owned by a pharmacist, who can’t own more than one establishment, that over the counter drugs can only be sold in drug stores, and that the price of medicines be capped. Similar laws exist in Spain, Germany, Portugal, France, Cyprus, Austria and Bulgaria, and were successfully defended before the European Court of Justice in 2009.

For obvious reasons multinational pharmacy corporations like CVS, Walgreen, and Rite Aid, plus retail goliaths like Wal-Mart, don’t like these laws, because they restrict the ability of these giant firms to dominate the market.

But the pharmacy law is hardly Greeks being “quaint” and old-fashioned. The U.S. state of North Dakota has a similar law, one that Wal-Mart and Walgreens have been trying to overturn since 2011. Twice thwarted by the state’s legislature, the two retail giants recruited an out-of-state signature gathering firm and poured $3 million into an initiative to repeal it. North Dakotans voted to keep their pharmacy law 59 percent to 41 percent.

The reason is straightforward: “North Dakotans have pharmacy care that outperforms care in other states on every key measure, from cost to access,” says author David Morris. Drug prices are cheaper in North Dakota than in most other states, rural areas are better served, and there is more competition.

The Troika is also demanding that Greece ditch its fresh milk law, which favors local dairy producers over industrial-size firms in the Netherlands and Scandinavia. The EU claims that, while quality may be affected, prices will go down. But, as Nobel Laureate economist Joseph Stiglitz found, “savings” in efficiency are not always passed on to consumers.

In general, smaller firms hire more workers and provide more full time jobs than big corporations. Large operations like Wal-Mart are more efficient, but the company’s workforce is mostly part time and paid wages so low that workers are forced to use government support services. In essence, taxpayers subsidize corporations like Wal-Mart.

A key demand of the Troika is “reform” of the labor market to make it easier for employers to dismiss workers, establish “two-tier” wage scales—new hires are paid less than long time employees—and to end industry-wide collective bargaining. The latter means that unions—already weakened by layoffs—will have to bargain unit by unit, an expensive, exhausting and time consuming undertaking.

The results of such “reforms” are changing the labor market in places like Spain, France, and Italy.

After years of rising poverty rates, the Spanish economy has finally begun to grow, but the growth is largely a consequence of falling energy prices, and the jobs being created are mostly part-time or temporary, and at considerably lower wages than pre-2007. As Daniel Alastuey, the secretary-general of Aragon’s UGT, one of Spain’s largest unions told the New York Times, “A new figure has emerged in Spain: the employed person who is below the poverty threshold.”

According to the Financial Times, France has seen a similar development. In 2000, some 25 percent of all labor contracts were for permanent jobs. That has fallen to less than 16 percent, and out of 20 million yearly labor contracts, two-thirds are for less than a month. Employers are dismissing workers, than re-hiring them under a temporary contract.

In 1995, temporary workers made up 7.2 percent of the jobs in Italy. Today, according to the Financial Times, that figure is 13.2 percent, and 52.5 percent for Italians aged 15 to 24. It is extremely difficult to organize temporary workers, and their growing presence in the workforce has eroded the power of trade unions to fight for better wages, working conditions and benefits.

In spite of promises that tight money and austerity would re-start economies devastated by the 2007-2008 financial crisis, growth is pretty much dead in the water continent-wide. And economies that have shown growth have yet to approach their pre-meltdown levels. Even the more prosperous northern parts of the continent are sluggish. Finland and the Netherlands are in a recession.

There is also considerable regional unevenness in economic development. Italy’s output contracted 0.4% in 2014, but the country’s south fell by 1.3%. Income for southern residents is also plummeting. Some 60% of southern Italians live on less than $13,400 a year, as compared to 28.5% of the north. “We’re in an era in which the winners become ever stronger and weakest move even further behind,” Italian economist Matteo Caroli told the Financial Times.

That economic division of the house is also characteristic of Spain, While the national jobless rate is an horrendous 23.7 percent, the country’s most populous province in the south, Andalusia, sports an unemployment rate of 41 percent. Only Spanish youth are worse off. Their jobless rate is over 50 percent.

Italy and Spain are microcosms for the rest of Europe. The EU’s south—Italy, Portugal, Spain, Greece, Cyprus, and Bulgaria—are characterized by high unemployment, deeply stressed economies, and falling standards of living. While the big economies of the north, France, Great Britain, the Netherlands, and Germany, are hardly booming—the EU growth rate over all is a modest 1.6 percent—they are in better shape than their southern neighbors.

Geographically, Ireland is in the north, but with high unemployment and widespread poverty brought on by the austerity policies of the EU, it is in the same boat as the south. Indeed, Greek Finance Minister Euclid Tsakalotos told the annual conference of the leftwing, anti-austerity party Sinn Fein that Greece considered the Irish “honorary southerners.”

Austerity has become a Trojan horse for multinational corporations, and a strategy for weakening trade unions and eroding democracy. But it is not popular, and governments that have adopted it have many times found themselves driven out of power or nervously watching their polls numbers fall. Spain’s rightwing Populist Party is on the ropes, Sinn Fein is the third largest party in Ireland, Portugal’s rightwing government is running scared, and polls indicate that the French electorate supports the Greeks in their resistance to austerity.

The Troika is an unelected body, and yet it has the power to command economies. National parliaments are being reduced to rubber stamps, endorsing economic and social programs over which they have little control. If the Troika successfully removes peoples’ right to choose their own economic policies, then it will have cemented the last bricks into the fortress that multinational capital is constructing on the continent.

In 415 BC, the Athenians told the residents of Milos that they had no choice but to ally themselves with Athens in the Peloponnesian War. “The powerful do whatever their power allows and the weak simply give in and accept it,” Thucydides says the Athenians told the island’s residents. Milos refused and was utterly destroyed. The ancient Greeks could out-barbarian the barbarians any day.

But it is not the 5th century BC, and while the Troika has enormous power, it is finding it increasingly difficult to rule over 500 million people, a growing number of whom want a say in their lives. Between now and next April, four countries, all suffering under the painful stewardship of the Troika, will hold national elections: Portugal, Greece, Spain and Ireland. The outcomes of those campaigns will go a long way toward determining whether democracy or autocracy is the future of the continent.