Third of three articles. Read the second article here

When money keep silent, the liberal democracy is gasping:The EU in East Europe and the Black Sea region after the fall of communism

By Radu Toma

Hungary

In May 1989, Hungary dismantled 245 km of barbed wire from the Iron Curtain on the border with Austria and thus became the first country to announce to the world the imminent collapse of communism, and to Eastern Europeans, freedom. Then followed the ‘awards’ in the form of funding, in a few years it attracted $ 18 billion in direct investment. But, after a while, the first signs of the unseen face of capitalism appeared, the less attractive one. If in Poland a terrible economic shock therapy produced, over several years, extremely high social costs, in Hungary the economic and social agony began immediately, as early as 1990-92, when the country lost 70% of its market from the East, 800,000 jobs and the cheap energy resources from the former Soviet Union – Russian oil and gas previously received at political, ‘brotherly’ prices. After another 20 years of neoliberal reforms and experiments, the transition to the market economy, accession to everything that means West – EU, Schengen, NATO, OECD, WTO, IMF, World Bank, etc. and after $ 70 billion of foreign direct investment, Hungary was nearly suffocated by an external debt of $ 10 billion in 1989 which reached to 187 billion and 115% of GDP on December 31, 2012. Hungary was close to collapse and, led by Viktor Orbán and his party, Fidesz, it radicalized.

It radicalized and offered to the world another two international paradoxical premieres. First, that its new prime minister, Viktor Orbán, a ‘Hugo Chavez of Central Europe’, shortly after coming to power went at loggerheads with the EU, ‘an empire of bureaucrats’, where ‘unacceptable decisions’ are made. He strongly criticized the IMF and the United States and abruptly interrupted negotiations with the EU and the Monetary Fund for a $ 20 billion loan, he said that Hungary’s downgrade to the ‘junk’ category by Moody’s, S&P and other international rating agencies, was ‘unfounded and falls into a series of financial actions against Hungary’; he stated that the European Parliament ‘represents a danger to the future of the European Union.’ He clammed up when Jobbik, the Hungarian nationalist radical party, the third largest in the country, present in the Hungarian Parliament and the European Parliament, went out on the streets of Budapest and called for a referendum for Hunexit, considering that Hungary ended up being a simple marketplace for west-European companies, a source of cheap labour and a place of storage for the west-communitarian garbage. The second premiere was that, exactly the opposite of Janos Kadar’s ‘communism goulash’, from the 60s-70s, Orbán and his party, Fidesz, decided to return to the benefits of regional economic development and launched, since 2010, the doctrine of ‘opening to the East,’ towards the countries of the former Soviet Union, Central Asia and China, an apparently paradoxical conclusion, after more than two decades of neoliberal indoctrination.

As a result, the strongest shot in Brussels was and remains consistently aimed against Orbán. For more than eight years, since he returned as prime minister, he has been called all sorts of names: populist, autarch, irredentist, putinist, trumpist, dictator, etc. In reality, issue no. 1 with him is that he was the first post-communist European leader who, instead of praising the neoliberal capitalist system, listed its minuses. Eurosceptic, soft populist, conservative and nationalist, he has for many years stirred controversy with statements against liberal democracy, against Soros, NGOs, etc. In 2014, in a speech delivered in Tuşnad, Romania, he first spoke of ‘illiberal democracy’, that is, he rejected the classical liberal theory of the state as an association of individuals and replaced it with a national, traditional, sovereign community, based on the Christian family, on the preservation of cultural heritage, etc. In a word, he defined the ‘illiberal’ state.

But what makes most of the EU-Budapest dispute irreconcilable is the inflexible position of both sides regarding Islamic immigration to Europe. In October 2016, in Hungary, a popular referendum rejected with 3.3 million to 55,000 the mandatory quotas of immigrants established by the EU. Then, once again defying Brussels, Budapest electrified the barbed wire fence at the border with Serbia.

What is the ‘Hungarian fashion’ for the year 2019? Continuing the massive change of the game rules; nationalism on the rise, their back turned to the EU, going on their own political and economic path; pushing the EU into the corner, to cause it to break its own rules of democracy and to become a demokratur (ger.), that is, a dictatorship of democracy; the constitutional reform brought to the very end; nationalization of at least 50% of the banking sector and public utilities (electricity, gas, water, transport); a war declared to the neo-colonialism brought from the West; housing and health taken form under the tyranny of the neoliberal market; support for pro-family and religious NGOs; Hungary – a functioning democracy for all; Hungary – a country of Hungarians.

In May 1989, Hungary cut down a barbed wire fence of 245 km, so that Eastern Europeans could reach free to Brussels, Berlin, or wherever they wanted. In 2015, it erected a 175km barbed wire fence, to protect Eastern Europeans from the reckless plans from Brussels, Berlin, or where they came from. Another wire fence, still barbed, imaginary, continues to be raised around the economic neoliberalism, to ward off the Hungarian people.

Equally, the same Hungary, for almost 20 years, has made from its economic and commercial openness towards the countries of the former USSR and other Asian countries, a key element of its foreign policy. A foreign policy much criticized during these two decades but confirmed by the manifested concern of Europe’s biggies, Germany, France and Italy, to move towards the political relations’ relaxation and to serious business with Russia and other former Soviets. The striving and perseverance of Hungary on this road can be an urge for reason and action for countries such as Ukraine, Georgia, or the Republic of Moldova, from the Black Sea, who are eager to formally establish their relationship with the Euro-Atlantic world.

*

After 1990, the average unemployment rate of 12% for 1991-1994, inflation, devaluation of the forint, rising prices, in addition with the collapse of exports to the former Soviet bloc, all these added made the transition in Hungary very difficult. The Antall government tried a few market reforms, but without the former exports of industrial products to the East, GDP has substantially declined, in a very short time. In March 1995, Prime Minister Gyula Horn imposed a drastic austerity, the deficit was reduced, and it was possible to temporarily waive IMF financial assistance. The government’s privatization program ended in 1998, but foreigners controlled 70% of financial institutions, 66% of industry, 90% of telecommunications and 50% of trade. From 65% -70%, as was its trade with the former CAER partners, by the end of 1997 Hungary’s trade with the EU and OECD countries reached 80%, Germany became its major partner, trade with the US reached one billion dollars. Over 35% of total foreign direct investment in the East landed in Hungary, from them six billion were from America. But all this did not help the economic development of the country, a healthy trade and a large, stable market were lacking. Aware of this state of affairs, the government of Péter Medgyessy, installed on May 2, 2002, said it would give priority to the resumption and development of trade and economic relations with Russia and other former Soviets. But the visit of the Prime Minister to Moscow did not produce results, things have remained, on both sides, at a declarative level. The Hungarian-Russian bilateral trade recovered somewhat in 2004, when Hungarian exports were $ 740 million, and Russian imports 3.2 billion. In 2009, Russia became Hungary’s second largest trading partner, after Germany.

Prime Minister from 2004 to 2009, Ferenc Gyurcsány promised in 2006 a ‘reform without austerity,’ but in October 2008 had to take $ 25 billion from the IMF to restore investor confidence. There were years when the consumption had considerably dropped, the euro and the Swiss franc sent the forint down, and, with 60% of the bank loans being in these two currencies, the population lost enormously. However, relevant in the second term of the socialist prime minister was the fact that the Russian-Hungarian relations experienced a remarkable revival. Gyurcsány had several meetings with Putin, two only in 2006, and the parties created a Hungary-Russia intergovernmental commission for trade and economic cooperation. In 2008, bilateral exchanges reached a record $ 6.06 billion and maintained an equal level in 2010. The Hungarian prime minister has repeatedly made public statements that Hungary will participate in the Russian project of the South Stream gas pipeline, that Mol and Gazprom will jointly build natural gas reservoirs in Hungary for supplying the EU, that the State Development Bank of Hungary will finance the Hungarian section of the pipeline, etc. Over the years, Gyurcsány has refused to join and comment on EU criticism of Moscow regarding the state of democracy in Russia, or the war in the Caucasus and the so-called question of Georgia’s territorial integrity. During his mandate, Hungary was classified by the Council of Foreign Affairs of Europe (ECFR), same as Slovakia, as a ‘pragmatic friend’ to Russia.

The big surprise in Budapest’s relations with Moscow came on May 29, 2010, when Viktor Orbán, after an eight-year break, became prime minister again. Notorious since 1998-2002, from his first term as prime minister, for anti-Russian rhetoric and for his older jokes, such as ‘I don’t want to be the happiest Gazprom storage room,’ in 2008 he sided with Georgia in the Caucasus war, etc. but in 2010 he turned 180°, abandoned the Russophobic outbursts and the concerns about Moscow, and launched a powerful political, media and image operation, of rapprochement and cooperation with Russia. Putin ‘understood’ Orbán, realising that the character, hyper but without personal anti-Russian feelings when he had the aforementioned outbursts, tried to make some political capital for his party, at home …

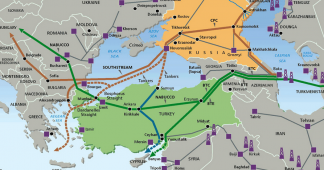

Hungarian-Russian trade, of over $ 11 billion in 2012 and growing steadily – Hungarian food products have been and still are very well sold in Russian stores, everywhere – did not fully reflected the real dimensions of the economic cooperation. This has become a true long-term partnership, with mutual investments of $ 5 billion in 2012, and other major financial resources, with modern projects in the area of high technologies, etc. Within this cooperation, energy took first place. The agenda of the Putin-Orbán meeting in Moscow in January 2013 was dominated by oil and natural gas, by the chances of the Russian company Atomstroyexport to build reactors 3 and 4 at the nuclear power plant in Paks, Hungary, a multi-billion dollar business; by the extension of the natural gas contract for Hungarians, due to expire in 2015; by the beginning of the South Stream pipeline construction, having an important Hungarian direct participation and an annual royalty of billions of dollars for Hungary, obtained from the gas transiting its territory, a project and a business opportunity which subsequently failed at Western pressures, etc.

In one word, it became obvious that the Russian side was pursuing, and the other side accepted, the establishment of Russia’s long-term strategic domination on the Hungarian energy market. In the years 2012-2013 the Russian-Hungarian bilateral economics has become somewhat of a permanent item in the ‘News of the day’, in all the Hungarian media, on television, radio, in print and online. Thus, the local and international public learned that the Russians were the majority shareholders in the national airline of Hungary, Malev, that the foreign ministers Lavrov and Martonyi met regularly, in Moscow or Budapest, in 2013 they met three times; that the former expressed satisfaction with Hungarian interest and investments in the regions of Russia, the Urals and Western Siberia, where a Hungarian consulate was opened in Yekaterinburg; that the Foreign Minister, Péter Szijjártó, decorated Viktor Zubkov, CEO of Gazprom, with the ‘Hungarian Order of Merit’, a high Hungarian distinction, for contributing to the development of Hungarian-Russian relations; that the Russian company Surgut had bought 21.2% of the shares held by OMW at MOL, with $ 1.4 billion and had become the major shareholder, and that the prime minister Orbán announced he would repurchase former national goods, sold previously to foreigners, such as the power plants from the French, the gas distribution from Germans, the legendary Ferencváros football team form the English and MOL from the Russians. At the Putin-Orbán meeting, on January 31, 2013, great words were spoken, the Russian president said: ‘We have a transparent, friendly, pragmatic relationship. Without a doubt, Hungary is our priority partner in Central Europe, our relations are developing in all directions.’ Charismatic and with excellent political communication, Orbán raised, and replied: ‘We would like a stable partnership with the great Russia, a great power, with a great past and a great future. It is clear that, after the current crisis is over, Russia will play a special role.’ Big words have been said, but the Hungarian prime minister has already begun to face at home the political dogmas of Brussels and the anger of the monopolistic multinationals and banks, which saw their hyper-profits in Hungary taxed extra, actually brought to the average level of EU, and divided with the Hungarian population. This was a situation in which he could only hope that his economic doctrine of ‘opening up to the East,’ to the former socialist countries, the former Soviets, Russia, etc. will function as an antidote to the eventual chicane and economic and financial ‘blockades’ from the West and, above all, will help him win the parliamentary elections next spring, 2014, and remain in power. He won them. Easy. His policies, including ‘Opening towards East,’ have proved popular.

But, the same spring of 2014, which was auspicious for the government of Viktor Orban, proved to be unfavourable for Russian-Hungarian economic and trade exchanges. Following the referendum of the Crimean population on the peninsula’s independence, on March 16 and its return to Russia, on March 18, 2014, economic sanctions imposed on Moscow by the US, EU and other countries and international organizations have led to a drastic decline in trade between the two sides. Thus, from $ 8.5 billion in 2013, they decreased to $ 4 billion in 2015 (66), a decrease of over 60%. And further estimates indicated that not only Russia suffered, but also those who decided to sanction it (67), the losses of EU member states, including Hungary, in just one year, amounted to EUR 100 billion (68). A strong opposition against these sanctions was made by companies and business people in Italy, Greece, France, Cyprus, the United Kingdom, Slovakia, Austria, especially Germany (69) and so on. Exxon Mobil, US, reported losses of $ 1 billion in February 2015 (70).

For over five years Orbán of Hungary has remained the most vehement critic of the sanctions, saying that the European Union ‘shot itself in the foot’ by accepting these coercive economic measures (71). Foreign Minister Szijjarto added that ‘sanctions were not successful, as Russia was not brought to its knees and our economies suffered so many losses and, politically speaking, we have not made any progress with regard to the Minsk agreements (n.a. regarding Ukraine)’ (72). So, sanctions or not, largely ignored by Budapest, after 2015 the Hungarian-Russian economic exchanges began to recover, this creating a discomfort in the West, as political analysts and investigative journalists say, increased by the ideological and political links between Moscow and the far-right elites of Hungary (73).

In August 2013, in Budapest, Viktor Orbán shook hands with Sergei Kirilenko, president of the Russian state-owned company Rosatom, for the purchase of two reactors at the Paks nuclear power plant in the north of the Hungarian capital. Subsequent developments in the business have sparked widespread criticism in the West, in Brussels and in other parts, a political analyst in Budapest, the prime minister’s opponent, stated that Orbán will pay more in the coming years for Russia’s two reactors than for the defence budget demanded by NATO (74). The deal is financed by the Russian side (75) and was sealed without a public auction. It is clear that, in Hungary’s case, the Western economic sanctions did not work, moreover, they caused a serious retaliation of the two partners (76). The final contract was signed at the end of 2014, and the two nuclear reactors will supply over 50% of the amount of electricity produced in Hungary.

At present, the Hungarian-Russian economic exchanges revert to the normality of past decades, they increased by 30% only in the first semester of 2017 (77), after the Hungarian Foreign Minister announced a loss of 7 billion dollars caused by the economic sanctions in the years previous (78). The current cooperation extends in the fields of machine building and water management. And the same minister reminded that the leaders of the European Union had supported, not long ago, the establishment of a gigantic commercial region, from Lisbon to Vladivostok. ‘It would be good to return to that concept,’ he added, pointing out: ‘A war seems to unfold in the world trade, so it would be in Europe’s interest to re-establish the former cooperation with Eurasia, which essentially means with Russia.’ (79).

As Hungary shows at the moment in terms of economic capabilities, many of its industries – construction, banking, medical, etc. – could exploit their competitive advantages by extending to the East, especially in Ukraine and in regions of Russia, where other entrepreneurs, or investors in the West, would be limited by the rigor of the democratic approach, or of transparency.

*

Ann Hart Coulter, a woman in her 60s, is a conservative New York publicist, commentator on national TV stations MSNBC, CNN and Fox News and on radio stations, author of 12 American political books, many of them on the bestseller lists of ‘The New York Times.’ Her favourite readings are the Bible and Anna Karenina. Being born to a Catholic father and a Protestant mother, at a public conference she said: ‘Christ died for my sins, I care about nothing else, and nothing else matters.’ Immediately after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, in New York, she said that only Islamists could be behind them, that not all Islamists are terrorists, but that all those terrorists capable of killing thousands of people in one hour are Islamic. In 2007, in Southern California, she stated, ‘Islamic-fascism is a reality.’ She reacted instantly after the bloody terrorist attacks in Charlie Hebdo, Paris, on November 13-14, 2015 (130 dead and 368 injured), tweeting after one hour: ‘If we feel like it, we can wait until the following November, when the vote will take place, but Donald Trump was elected president tonight.’ As for Trump, the prophecy of Ann Coulter was fulfilled, and Orbán of Hungary was the first international leader to congratulate him on the victory (80).

Four days after the Charlie Hebdo attack, 1.5 million people marched through Paris. Viktor Orbán was one of the 40 leaders of the world leading the demonstrators, in solidarity with the freedom of expression and against terror. Today, after almost four years, we understand that the world, different countries, have reached different conclusions about the crimes in Paris and the terrorist attacks that followed. For the demonstrator Orbán, however, it was clear from that moment in Paris who were the ones bearing the blame: illegal migrants from the Islamic world and northern Africa (81). Returned home from the French capital, he said to a television station in Budapest: ‘We will never allow Hungary to become a destination for migrants. We want to keep Hungary what it is. Hungary.’ But, in 2015 and 2016, in addition to the wave of terror, Europe was hit by a second tide, of hundreds of thousands of migrants and refugees. By putting an equal sign between migrants and terrorists, Orbán tried to provide a simple explanation and a tailor-made solution. The majority of the newcomers are not refugees from war and persecution, they are economic migrants who want a better life in Europe, he said. Adding that, for Hungary and its demographic crisis, the solution is not migration, but encouraging Hungarian families to have more children. ‘If we want to have a Hungary of Hungarians and a Europe of Europeans, and surely that is what we want,’ he said on October 17 in Oradea, Romania, ‘then we must want a Christian Hungary and a Christian Europe, instead of what threatens us now – a Europe with a mixed population, lacking identity.’ For his words, in February 2018 the UN Commissioner for Human Rights called Orbán ‘racist and xenophobic’.

Since 2015 onward, Trump and Orbán have been walking the same path of anti-globalism and nationalism. Enemies of a dogmatic liberal democracy, worn out and tired, they have the same adversaries, Merkel of Germany, but also common friends, Netanyahu of Israel (82). They value each other and share the same admiration for their countries and nations. In 2018, after the third consecutive victory in the Hungarian parliamentary elections, Donald Trump called Viktor Orbán, and had only words of praise for Hungary, congratulated it and urged it to stand firm on the southern border (83). ‘In recent decades, the United States have been striving to make the world a better place, when in fact the world was against America’s interests. Under former administrations, especially that of Barack Obama, the United States believed that they knew what good, morals, justice and what humanity should be like, but in reality, they wanted to impose their will on it, including on Hungary. Mr Trump has decreed the end of this policy, and now Hungary no longer has to defend itself against American influence,’ Orbán told Radio Budapest, commenting on Trump’s anti-globalist speech at the UN (84).

At the end of 2018, it became clear that the world is undergoing profound transformations. The corporate capitalism embodied in the formula ‘liberal globalization’ ignored most and ended up being despised by most. At the level of nations, the scepticism towards the global economic order has reached emergency levels, see the case of France, the birth place of the modern era’s revolutions. The rebellion against the institutionalized forms of poverty, of those with yellow vests or not, seems unstoppable. An important international contributor to these mutations is the leader of Hungary. For several years now, his words have marked the way to a Europe of nations, of economic nationalism, a Europe other than that of a multicultural empire undemocratically controlled, not by elected leaders, but by brusselocracy, that is, by the bureaucrats in Brussels. On several occasions Viktor Orbán said:

– ‘We have to abandon liberal methods and current principles of organization a society;

– Hungary is against the export of democracy and opposes migration;

– When a mob bursts into your house, this is called an invasion;

– We will not import crime, terrorism, homophobia and the kind of anti-Semitism that sets synagogues ablaze;

– We cannot let Brussels put itself above the Law. We are not communists;

– The death penalty question should be put on the agenda in Hungary;

– We interpret our agreement with the International Monetary Fund – out participation in the IMF’s cooperation system – as a loan agreement. The IMF interprets it as an understanding of economic policies. We are not interested in signing agreements with the IMF on economic policies, as this would mean limiting the movement space of the Hungarian government, Parliament, legislators;

– The leaders of Europe always seem to emerge from the same elite, the same general frame of mind, the same schools, and the same institutions. And they take turns implementing the same policies;

– We want to keep Europe for Europeans;

– We’d accept Germany either allowing all migrants in or not allowing any in. But whatever Germany decides should only apply to Germany;

– The obstacle in our way is not Islam, but the bureaucrats in Brussels;

– To be clear and unequivocal, I can say that Islamisation is constitutionally banned in Hungary;

– In Hungary, if homosexuals want to live together, they can do so according to the provisions of the Civil Code. But what we call marriage is something that happens exclusively between a man and a woman. We are a Christian country. And this is a historical fact;

– It would be sad to give up religious faith, national identity, family and even sexual identity. This is not called freedom;

– We protect Europe in accordance with the European rules that say, that borders can only be crossed in certain places, with proper documents and only after the traveller has registered at the respective border point;

– We believe that without cooperation with the Russians we cannot achieve the goals we have set. The one who thinks that the European economy can be competitive without economic cooperation with Russia, the one who imagines that Europe’s energy security can exist without the energy coming from Russia, is a person trying to catch ghosts;

– The greatest danger for the future of Europe is not those who want to live here, but our own political, economic and intellectual elites, who want to change Europe against the will of the Europeans.’

*

After the fall of communism and capitalism’s return to the East, under the command of leaders fascinated by the siren song of liberal democracy, such as Viktor Yushchenko, Olga Tymoshenko, Arseni Yazeniuk, Petro Poroshenko and Mihail Saakashvili, Ukraine and Georgia have waisted three decades of hopes, efforts and a generation of people, being now still in a precarious and discouraging, less honourable state, of eternal candidates for joining the Euro-Atlantic organisations. After 30 years, the light at the end of the tunnel is still not visible for them. Budapest’s existential conflict with Brussels, as well as the mutual consensus and appreciation of Hungary and Viktor Orbán both in Washington and Moscow, is a lesson for Kiev and Tbilisi.

But, unfortunately, the elimination of deep rooted, historical disputes; of current conflicts, in ‘semi-frozen’ and often open forms; the ‘behind the corner war’ as a solution within everyone’s reach, at all times; finding a negotiation format acceptable to all involved, all these make from the attempt to reconcile local and international players from Ukraine, or Georgia, riparian to the Black Sea, an impossible mission in the foreseeable future.

Bulgaria

On a visit to Sofia in 1992, Boris Elzîn spoke of a ‘historical debt,’ from the 9th century, of Russia to Bulgaria – the Slavic alphabet of the Cyril and Methodius brothers – and after 20 years, in 2012, and still in Sofia, Patriarch Kiril of Moscow and all of Russia strengthened the words of the former Russian president and added that the Bulgarian Church, the oldest of all Slavonic churches, sent 990 priests and books to Kievan Rus’, ‘the first holy texts of the newly christened Russian people.’ From the other side, the first and greatest ‘historical debt’ of the Bulgarians to Russia is their deliverance in the Russian-Romanian-Turkish war from 1877-1878. Its closing date, March 3, ‘Liberation Day,’ has become the National Day of the country. The equestrian statue of the Liberating Tsar Alexander II, one of the two existing in the world, is, since 2007, guarded in Sofia, in front of the Bulgarian Parliament (85); another 400 monuments, all over the country, are related to that event. In the last years others were added, erected from public money or with donations from Russia. Two Bulgarian cities and hundreds of streets and institutions bear the names of Russian soldiers, diplomats and doctors from that war. At the Academy of the Armed Forces of the Russian Federation and at the ‘Suvorov’ military school in Moscow, it is said that the former Russian imperial army is more frequent and festively commemorated in Bulgaria, than in Russia. In 2003 and 2008 Putin officially came to Sofia, 125 and respectively 130 years from the mentioned liberation war. The former Bulgarian President Gheorghi Pârvanov, in his double presidential mandate 2002-2012, travelled to Moscow 10 times, usually on the occasion of some historical celebration. On the 140th anniversary of the same national event, in May 2018, the last president of Bulgaria, Rumen Radev, met in Sochi with President Vladimir Putin, to strengthen the historical and cultural relations between the two countries, discussing Russian tourism in Bulgaria, large and fast growing again after Crimea 2014 and, in particular, to plan a new energy cooperation – a possible natural gas pipeline ‘Bulgaria Stream’, a remake after the departed South Stream project abandoned by former pro-western President Rosen Plevnielev (2012 -2017), (86). In Sochi, the Bulgarian president stated, among other things: ‘Russia’s victory (in 1877-78) made Bulgaria appear on the map of Europe. The purpose of my visit is to restore the dialogue between our countries on the highest possible level’ (86). His offer was immediately followed by a similar one by Prime Minister Boiko Borisov, in Moscow, both fuelling speculation that Sofia will turn its back to the West and realign to Kremlin (87). We could say, then, that beyond the regimes seen by the two countries in over 100 years – monarchy, fascism, communism and capitalism – the common Slavic origin and the two ‘historical debts’ govern the Bulgarian-Russian relations.

However, today, economic relations between the parties, rather than history, dominate the agenda of the Bulgarian-Russian bilateral talks. VTB, a large Russian bank, has been playing a predominant role in the Bulgarian economy for a long time, the public interest information and the media sources are connected to Moscow and are echoing the messages from there. Human interconnections are also long-lasting. Many top politicians, diplomats, businessmen, administration officials, military and technocrats come from parents educated in the former Soviet Union. Russian citizens have bought 65,000 apartments and houses in Varna and Burgas in recent years, living there most of the time. The Russian language has become a common communication tool throughout the Bulgarian Black Sea coast. On the other side of the country, in Sofia, Russia can count on many friends. Political parties, social organizations, lobbyists and influence groups speak openly about their ties with Moscow, they praise the benefits of a closer cooperation with the Russians in the field of energy, strongly criticizing the economic sanctions of the West and pointing the finger at the EU and the US, as sources of all the misfortunes suffered by Bulgaria after 1989. Vladimir Putin has loyal fans there, who wear black-orange ribbons in public gatherings, similar to those worn by Russian separatists in Donbas and other parts of Ukraine …

In 1996, hundreds of thousands of Bulgarians enthusiastically welcomed US President Bill Clinton in Battenberg Square, Sofia, and long advocated for their country’s entry in NATO. After three years, in 1999, during the war in Yugoslavia, 80% of Bulgarians opposed the aggression and the use of Bulgaria’s airspace for NATO missions and were against an independent Kosovo. The same hundreds of thousands of people who wanted their country’s entry into the North Atlantic military alliance, in the same Battenberg Market in Sofia, publicly expressed ‘sympathy for their Slavic Orthodox Christians, the Serbs’ (88). After 19 years, on January 11, 2018, during a visit to Bulgaria by the President of the European Commission, Jean-Claude Juncker, tens of thousands of protesters went out on the city streets, and flags of the European Union and NATO were set on fire in Sofia… (89)

*

Before 1989, Bulgaria followed the Soviet model of economic development more than any other socialist country in the East. It was the most active member of CAER in terms of relations with the former republics of the Soviet Union and with Russia itself. In those years, this country shifted from agricultural production to industrial production, its trade was oriented almost entirely to the former USSR and the Eastern socialist countries, the Bulgarian economy being identical with the Soviet one. From the post-war period to the 1950s, disciplined, the Bulgarians worked tooth and nail (‘Balkan Prussians,’ said Bismarck), their five-year plans yielded better results than elsewhere, the political stability of the regime was greater than to the others Eastern Europeans, no uprisings, no revolutions, dissenters not more than the fingers of one hand. But after the fall of communism and the loss of the Russian market, everything collapsed dramatically: the arms industry, after the disappearance of the Warsaw Pact, the electronic industry producing automation, signalling and control systems for the railways of the former Soviet Union, the car manufacturing industry, producing trucks and buses, the production of forklifts, etc. In 1991, 49% of Bulgaria’s exports were still going to Russia and 43.2% of its total imports came from there. In the following year the standard of living decreased by 40% (it returned to the one before 1989 only around 2004). All that happened proved that no Eastern country was more economically affected by the collapse of communism as Bulgaria, none was so dependent on trade with Russia, the former Soviets and former Eastern European socialists.

In the early 1990s, a 600-page ‘Action Plan’ prepared by a group of 18 American experts, including VIP members of the former Reagan administration, under the auspices of the US Chamber of Commerce and enthusiastically supported by President-Philosopher Jeliu Jelev, seemed to be the magic wand that will turn in a moment, obviously in a very good direction, everything, the old bad habits, the lives of people, Bulgaria (90). But the not yet completed transition, even after 30 years, towards the benefits of neoliberal capitalism has proved to be an impossible mission, with social costs, economic sacrifices and demographic movements, unimaginable for the vast majority of Bulgarians. Inflation reached hallucinatory numbers; its record monthly rate was 242% in February 1997. Signs of recovery appeared only after 2000, then in the years 2001-2005, of Simeon II of Saxony-Coburg and Gotha governance, the former minor king of Bulgaria in 1943-1946 who returned from his Spanish exile, an anaemic growth followed together with some budget surpluses, severely swept by hyperinflation (91).

Bulgaria’s long-needed and efficient economic and trade relations with the East, nevertheless, remained ‘frozen’ under the pro-Western governments Ivan Kostov and Simeon II (1997-2005). However, during the same period, the Moscow-based company Luk Oil fully acquired Neftuchim, the country’s only oil refinery, in Burgas, as part of the ambitious privatization program of the centre-right, pro-American government of Ivan Kostov. Russia’s economic influence continued to grow steadily after 2000, the government of Simeon II re-launched the Belene nuclear plant project. Then, under the government of Sergei Stanishev, August 2005-July 2009, of the Bulgarian Socialist Party (former communists), the Bulgarian-Russian bilateral trade, of $ 4 billion, exceeded the level before 1989. During his visit to Moscow in May 2007, it was stated that there is a need to resume closer bilateral economic ties. There were also discussed there, for the first time, strategic energy projects with a political impact, including the future South Stream pipeline, via the Black Sea and Turkey, in order to avoid the transit of Russian natural gas through Ukraine and Romania.

Subsequently, after the country’s accession to the EU, the ‘battle for Bulgaria’ between East and West started in force in January 2008, when Putin, in an interview with the Bulgarian and Russian press, made important political statements regarding bilateral relations, and expressed his belief that Bulgaria’s accession to NATO and the EU does not constitute a barrier for the deepening of those relations, and that new links are facilitated by both countries, in line with the incurred changes, with the new configuration of Europe and with major reforms, both in Russia and in Bulgaria. To avoid leaving any doubt on the two countries’ direction together, the Russian president said: ‘Of course, the national interest, a healthy pragmatism, mutual respect and mutual profit are the vectors of today. No political trends, nor the rapid evolution of the present world, can influence the partnership to which Bulgaria and Russia are destined to’ (92). Then, after he initiated the package of three Bulgarian-Russian joint energy projects, of billions of dollars – Belene nuclear power plant, Burgas-Alexandroupolis oil pipeline in Greece, and South Stream – on February 4, 2009, in Moscow, President Pârvanov inaugurated the ‘Year of Bulgaria in Russia’, opened with a gala concert at Balşoi Theater and followed by countless forums and business meetings, by ‘Sofia’s Days’ in Moscow and ‘Varna Days’ in Skt. Petersburg etc. From 2009, the Bulgarian economy has begun to recover, but Sofia’s centre-left political management has failed to eliminate the structural deficit from Russian-Bulgarian trade dominated by Luk Oil and Gazprom’s exports to Bulgaria, especially after the global crisis proved how much Bulgaria depends on Russia for energy and other raw materials. ‘The speed’ and the new dimensions of the Bulgarian-Russian relations in 2009 have not been unnoticed and provoked the westerners’ reaction. A year and a half after joining the European Union, a negative report from the European Commission, in July 2009, concernedly commented the political situation in Bulgaria (fraud, corruption of politics and justice, etc.), finding that it is moving away from Brussels. It considered almost dangerous its total dependence on Russian natural gas (92%) and pointed out that Sofia could again enter the sphere of influence of Moscow, if a turnaround will not occur (93).

Apparently, the ‘recovery’ has happened. Boiko Borisov, ‘the people’s man’, as the Western media said, and the head of the Citizens for European Development of Bulgaria (GERB) party, pro-European, pro-American and disinterested in Russia as an ‘older brother’, was installed on July 27, 2009 as Prime Minister, following the pro-Russian Stanishev and after winning the parliamentary elections with a ‘tough’ anti-corruption program, organized anti-crime, anti-fraud, justice rehabilitation program, etc. For nearly four years, as he governed Bulgaria, he tried to develop his own 10-year energy development plans and, at the same time, to put the Bulgarian-Russian strategic energy relationship, more than 60 years old, on the rocks. On his appointment, the first announcement made by Prime Minister Borisov was that all three energy projects negotiated with the Russians will be reviewed. The first, the nuclear plant, was immediately ‘revised’, meaning that it was stopped, with the excuse that the Germans refused to finance it, and that Bulgaria would be outweighed by costs. The following year, 2010, the Belene project was ‘frozen’ indefinitely, and in 2012 officially abandoned, on January 27, 2013 600,000 Bulgarians supported it in a referendum organized by the opposition, but the prime minister stubbornly ended it in Parliament, in February 2013, a few days before resigning. It was said afterwards that the next return of the Socialists to governing will bring high chances for it to be resumed. The second project, signed in March 2007 by the Prime Ministers Stanishev and Kostas Karamanlis, in the presence of Putin, the Burgas-Alexandropulos pipeline, for gas transport from Caspica to Greece and Italy, after negotiations that dragged on for years, was abandoned by the government Borisov in December 2011, under the pretext of environmental degradation and the too small profit resulting from the short gas transit through Bulgaria. It became obvious that, in those years, Borisov played the political games of others in the case of the Belene power station, as well as in the Bulgarian-Greek pipeline, aiming to prevent a penetration and the energetic control of the Russians in the Balkans and the Mediterranean. Finally, regarding the third project, after playing on two ends and seeing that the other business, the Nabucco gas pipeline, of the Westerners, is endlessly delaying and staggering, Borisov had no objections and, on November 15, 2012, signed the final agreement with the Russians for the South Stream pipeline. Its section in Bulgaria was to be 540 km long and cost $ 3.3 billion. But, on February 20, 2013, ‘the people’s man’ was thrown out from the government by … the people, by a national wave of protests, being accused of the aberrant increase of the energy costs, the collapse of the living standard, corruption, old ties with organized crime, illegal activities, tax fraud, money laundering, blackmailing and threatening the media, racism and xenophobia. After the departure of Borisov the Russians were offered the upgrading of the old nuclear power plant in Kozloduy and, after Plamen Oreşarski’s government coming to power, in May 2013, supported by socialists, also with the project of the second nuclear power plant in Belene. Sofia remained interested in eliminating intermediaries from the Russian gas purchases, and Moscow was to provide annually Bulgaria with significant amounts of transit charges from the Russian gas passing through the South Stream pipeline.

Not only the energy chapter existed in those years in the Bulgarian-Russian economic cooperation. The Bulgarian Minister of Agriculture negotiated in Moscow, in 2012, the restoration of what was called during the CAER the ‘Green Corridor’, for the expanded and rapid export of Bulgarian agricultural products to the former Soviet Union. In the following year 2013 38 companies from Bulgaria sent their agri-food products to Russia.

*

The Crimea episode in the spring of 2014 was, however, a not so easy shock for Bulgarian-Russian relations. The return of the peninsula to Russia and the ensuing armed conflict in eastern Ukraine, with a majority Russian population, put Bulgaria in a difficult situation. The cabinet of the Socialist Prime Minister Oresharski was forced to navigate between the commitments to the West, and the loyalty to the historic, solid relationship with Russia. It relied on the parliamentary support of Ataka, a pro-Kremlin party and against ‘US neoliberal colonialism’, as a source of negative economic developments in Bulgaria since 1989. On March 3, 2014, Ataka held in Sofia a rally under the slogan ‘Russia and not the European Union freed us from Turkish slavery,’ and in May, during the campaign for European parliamentary elections, Bulgarian nationalists demonstrated under the slogan ‘Ukraine is an artificial state, just like Macedonia’ (94). From the first moments, when Euro-Atlanticists spoke of economic sanctions against Moscow, Foreign Minister Kristian Vinegin stated that Bulgaria should act prudently, lest they do more harm to the EU than to Russia. As it is known, for five years now the warning of the Bulgarian minister has been reinforced by Berlin, Paris, Rome, Warsaw, Prague, Bratislava, Budapest, etc. who count how much they lose year after year and continually complain about the damages caused by those sanctions. But pro-Western President Plevneliev imposed a tougher anti-Russian direction and everyone was at loss, Russian energy exports to Bulgaria fell by 18% in 2014 (95), the number of Russian tourists decreased by 50% in the next year, 2015 (96). It seemed that Bulgaria had become a real ‘battlefield’ between West and East.

In November 2014, former Prime Minister Boiko Borisov returned to government, apparently with the lesson learned, as he gave up his previous anti-Russian vehemence and settled on a middle ground. His caution was confirmed in March 2015 by a public opinion poll, which revealed that, after Crimea 2014, 72% of Bulgarians maintained a positive opinion on Russia, 61% were opposed to sanctions against Moscow and, most shockingly, 62% preferred Russia over the EU and NATO (97). Shortly after that poll, in July 2015, Prime Minister Borisov downright buried the western sanctions, saying that ‘it is not our desire and purpose to freeze relations with Russia,’ and a spokesman for the EBRD, the prime minister’s party, rejected the Western philippics against Moscow, stating: ‘It becomes even clearer that we were presented with a false idea about Russia. Its real priorities are very different from those of an aggressive, constantly offensive state. Due to its geopolitical position and its strong spiritual and cultural ties with Russia, Bulgaria is called upon to act as a mediator and to eliminate tensions’ (98).

From the 2014 Crimea episode until now, Bulgaria is under the special, continuous supervision of Brussels through the Cooperation and Verification Mechanism (MCV). They are accused of endemic corruption – it is alleged that one in five Bulgarians made once a corrupt transaction. In the West, it is increasingly insisted that the Bulgarian judicial system has failed, that it hinders the country’s development and the arrival of investors. It is insisted that Bulgarians obstruct and crush banks with foreign capital, that government officials are trying to start ‘very controversial’ energy projects with Russia and China, while other EU members are running away from the energy dependence on Moscow. It is claimed that the Bulgarian media is submerged in fog. Also, in the West, in Brussels, the question now arises: How much longer will the European Union allow Bulgaria to walk on a tightrope, at such a dangerous height? (99)

It is clear that the EU is beginning to lose patience with Bulgaria. But it seems that the relationship has begun to balance, and Bulgarians seem to be losing patience with the EU.

Meanwhile, after Crimea 2014, trade with Russia has rebounded and started to grow, in 2017 they reached $ 3.5 billion, exceeding the level of 2013. Similarly, the number of Russian tourists in Bulgaria increased in 2017 above the level of 2013 (100). It is believed that statistics, not yet published, will report for 2018 a record number of tourists (101).

After Crimea 2014, in the case of Bulgaria, the EU’s economic sanctions against Russia simply did not work.

*

The year 2018 did not record any wars, no major crises, no setbacks and no memorable resolutions, but it left a strong sense of calm before the storm. The global economic crisis is floating in the air, the fault line in the Atlantic is widening from downwards towards the surface and furthers America from Europe. The Hamlet’s dilemma has changed – ‘To Brexit or not to Brexit’. Incited by an extra 2-3 eurocents at the petrol pump, France’s ‘yellow jackets’ want to change ALL corporate capitalism. With 14 years in the position, Angela Merkel finishes the German chancellorship in third place, after Bismark and Kohl, on a par with Adenauer and ahead of Hitler. The populism is unleashed in Europe before the European elections in May. The twilight of the UN, IMF and WTO gods started. Middle East is on the brink of chaos after Trump’s latest announcement about the withdrawal from Syria. There are centrifugal trends in the EU. NATO is looked at cross-eyed from both extremes, from Washington and Eastern Europe. In May 2018, in just one week, three EU leaders visited Russia: Merkel of Germany, Macron of France and Radev of Bulgaria. The first two spoke about the EU’s unity, the third of other interests of his country in the Eurasian space. After 10 years of apparent accession of Sofia’s presidency to the rigors of Brussels, the question arose again: Will Bulgaria be again the Trojan horse of Russia in the EU?

Recent developments in Bulgarian policies indicate a warming of the relations between Sofia and Moscow. Rumen Radev, known for his pro-Russian stance, replaced Rosen Plevneliev, an outspoken Atlanticist. Borisov has returned, his GERB remains in power, and in the Parliament the pro-European liberals have given up their positions in favour of the right-wing nationalists, many of whom have welcomed the return of Crimea to Russia. Borisov refused to support Romania’s president Iohannis’ initiative to develop a permanent NATO fleet on the Black Sea. He also refused to expel Russian diplomats after the UK’s Skripal case, delayed the decision to buy fighter jets from a North Atlantic alliance partner and resumed negotiations with Moscow for a $ 40 million contract to repair and modernize the old Russian MIGs from the Bulgarian Army’s arsenal. In this political atmosphere in Bulgaria, some even speak of the country’s exit from the alliance.

Prime Minister Borisov forgot all that he told about Russia in 2009 and, like others from the national political elites, probably began to believe that the relationship with the West does not bring him big dividends, but only advice and vague promises (102). Bulgaria did notice that sometimes the West is duplicitous. One of the first moves Borisov made in 2014 was to withdraw from the South Stream Russian-initiated project, hoping he would benefit from Western financial assistance to solve the problem of natural gas transit through his country. He received nothing, ended up with serious penalties, in return, the European leaders encouraged the construction of the North Stream 2 pipeline, from Russia to Germany, through the Baltic Sea. Today, the President and Prime Minister of Bulgaria are ignoring Brussels’ warnings and openly negotiate with Russia a possible Bulgaria Stream and other energy projects.

It is to be seen what pressure the EU will be able to put on Bulgaria in the near future and to what extent Sofia will back down.

*

On November 10, 1989, when the oldest communist leader in the East, Todor Jivkov (he ruled the country for 35 years, from 1954) was fired and sent to spend the rest of his days in his hometown, Praveţ, Bulgaria was the dawdler of the former socialist countries, with the lowest official income per capita. Three decades of neoliberal capitalism and 11 years of EU membership have failed to change anything, Euro-barometers continue to rank it also now as the poorest country in the Union. On January 11, 2018, the pensioners participating in the anti-EU and anti-NATO rally in Sofia carried mini-posters with a question addressed to Brussels: ‘How can I live with 85 euros per month?’ (103). Bulgarians claim today that they were living better in the times of the former regime, and when they are told they are nostalgic, they show figures, statistics and reports from the late ‘60s-’80s, drawn up by honourable Western institutions, the UN and its specialized agencies UNESCO, World Health Organization, FAO (World Food and Agriculture Organization), IMF, UNICEF, UNCTAD etc. That is, documents indicating in black and white that, at that time, the school in Bulgaria was among the first in the world and culture was a commodity; that Bulgarian, natural agri-food products were consumed at home and awarded in the West for their quality; that almost all families in urban areas had state-owned homes and bought new cars, not second-hands; that all Bulgarians went to the seaside for free, with the union, and unions had their own vacation houses there; that Jivkov had given the families from the cities a plot of land in the countryside, to cultivate it with vegetables and to raise small animals, etc. And that these essential advantages made the real wage of ordinary people significantly higher in those times, and all these have disappeared today, euthanized by the unleashed neoliberal capitalism (104). It is clear now, many say, that families’ income in Bulgaria was more consistent in the time of the social state, in terms of purchasing power, quality of food, of life, than today, after almost 30 years of liberal democracy and free market. In the past regime, the food quality control was very strict, today, say Bulgarians, is almost gone, the market was seized by shop-chains from the West, with high prices, monopoly and mediocre quality products.

In 1989, Bulgaria had a population of over nine million inhabitants, currently only seven million remain in the country, and demographers estimate that their number will continue to drop, to five million by 2050. More terrible than in the Baltic countries, the exodus causes Bulgaria to be considered by international experts as the country with the fastest population decline in the world. Villages and whole rural areas have been left empty due to migration to the cities, and the inhabitants of cities, especially university graduates (105), have left and continue to leave abroad (106).

In 1989, when the Berlin Wall fell, not knowing what it was about, Bulgaria accepted and supported a series of ideological schemes and development programs, manipulated by the supranational institutions of the IMF, the World Bank and a network of NGOs rapidly expanded by George Soros and others across the country – their number rose to 38,000 (?!). The UN agencies, the aforementioned financial authorities and the ‘Open society’ of the billionaire-charlatan organized and coordinated the transition using the same humiliating methods, ideas and language they had used for decades in the most backward countries of the Third World. The neoliberal economy and free market democracy have prospered (107), the capable and skilled labour force has migrated. The brain drain was devastating. The profitable heavy and manufacturing industries were demolished. In the shadow of foreign profits rushed out of the country, a few hundred or perhaps thousands of former villains, car thieves, insurance salesmen, former sportsmen, fighters who ended up the bodyguards of politicians and afterwards even politicians, top privatization gangsters etc. today are almost all millionaires, meaning respectable people.

Since November 10, 1989, since ‘tatko’ Jivkov – father Jivkov, as many Bulgarians remember him – ended his journey through life and returned home to Praveț, and to this day, the absolute majority of the Bulgarian people have fallen in the neoliberal trap.

But also, today Bulgaria is waking up.

And thus, the rising of the East is happening, from the Baltic Sea, to the Black Sea.

*

At present, in Poland, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary and Bulgaria, therefore in most Central and Eastern European countries, political management has three similarities: (1) the president-government consensus; (2) the existence of fundamental disputes with Brussels, political, economic and regarding the essence of the constitutional state, and (3) the economic reorientation more pronounced towards the Eurasian market. It is possible that Romania is heading in a similar direction, 2019 presidential elections will be decisive regarding the near future direction Bucharest will be heading towards. Socio-economic inequality out of any control, permanent austerity as a way of life, double-digit unemployment, massive emigration and negative population growth beyond the limit of demographic extinction, are problems that delegitimize the neoliberal state comfortably installed in the three Baltic countries after the fall of communism, 30 years ago. It can be said without mistake that from Tallinn to Sofia the danger of a possible rapprochement and re-orbiting around Moscow is seriously contested by an even more severe ideological stake: the escape from the neoliberal order and the new colonialism coming (again) from the West. The antidote? The return to the social and nationalist state, with its main component, the economic nationalism.

Bulgaria’s experience in the EU and NATO, on the one hand, and the solidity of its historical relationship with Russia, in Europe and the Slavic world, on the other, are of particular value to Ukraine. Any political, strategic decision, etc. of future Kiev should also incorporate the ‘Bulgarian lesson’. A lesson on the historical prosperity of pan-Slavism, on balancing policies, but also on priority economic interests, and on geopolitical survival at the geographical contact between Western Europe and Eurasia.

Equally, the ‘Bulgarian lesson’ is a precious experience for Georgia, the other aspirant to the Western European values, located on the opposite Black Sea shoreline.