27 September 2018

A bigger loan and the early release of funds were agreed on by Argentina and the IMF, despite warnings by labor unions.

Argentina’s government reached a new deal with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) Wednesday, securing the early release of funds and an adding US$7.1 billion to the US$50 billion stand-by loans closed earlier this year, despite widespread opposition from citizens.

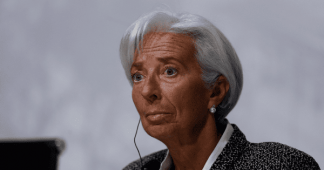

The agreement was announced late Wednesday by IMF chief Christine Lagarde and Argentina’s Treasury Minister Nicolas Dujovne in New York.

In exchange, the government will ratify the 2019 budget widely condemned by workers, unions, and citizens as a source of “more hunger and unemployment” during the national 36-hour, and another 24-hour strike, that brought the country to a standstill Tuesday. Lagarde called the budget “adequate and sustainable.”

President Mauricio Macri’s government also committed to an “anti-inflationary monetary policy” that will prevent the government from issuing currency and from intervening in a floating exchange rate in a climate of the rapid devaluation of the Argentine peso, which has undermined purchasing power and “annihilated” salaries. Since the beginning of 2018, the Argentine peso has lost 50 percent of its value.

“We are attacking the root of inflation,” Guido Sanderlis, the current president of the central bank, the third during Macri’s administration, said as he explained another round of monetary policy reforms.

According to Sandleris, the IMF agreement promotes a free-floating exchange rate as long as the price of the dollar stays within a fluctuating price range. The range will start at 34 and 44 pesos but will be updated on a daily basis to reflect a 3 percent monthly increase until the end of the year. By December the dollar could reach 48,08 pesos without state intervention according to observers.

If the price of the dollar exceeds these ranges, the Central Bank will be authorized to sell US$150 million of its national reserves a day. A measure some economists say is insufficient because “only one bank can demand that amount in one day,” Arnaldo Bocco, director of the Foreign Debt Observatory of the Universidad Metropolitana para la Educacion y el Trabajo (Metropolitan University for Education and Labor), explained.

After the IMF deal, the US dollar increased its value from 39.20 to 40.59 against the Argentine peso.

Opposition groups criticized the agreement calling it excessively monetarist and accusing the IMF and government of setting aside the real economy, production and industry.

Heterodox economists fear the measure will just induce further economic hardship to avoid a default.

Bocco warned local newspaper Pagina12 “the effect will be felt in economic activity. Credit will be scant and very expensive. They are trying to control inflation with more recession.”