By Julie Hyland

17 July 2018

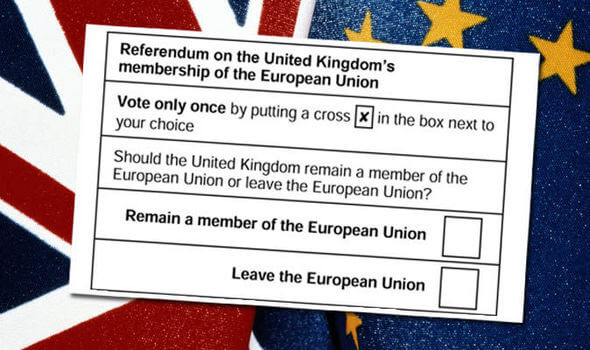

The European Union (EU) summit on the West Balkans in London last Monday was overshadowed by the political crisis in the Conservative government over Brexit.

Political and business leaders from Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kosovo, Macedonia, Montenegro, Croatia and Serbia attended, along with several EU leaders including German Chancellor Angela Merkel and Polish Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki.

The event was part of the Berlin Process, set up by Germany in 2014. It was intended to keep the Balkan countries firmly on side, as part of EU and NATO moves against Russia, under conditions in which the EU effectively halted the accession process following the 2008 financial crash. Talk now is that no country will be accepted before 2025 at the earliest.

Commentators had already noted the irony of London hosting the summit when it is attempting to exit the EU. But the UK is keen to prove that it will continue to play a role in Europe—especially in such strategic areas—post-Brexit.

The government press release on the meeting stated, “The UK wants a strong, stable and prosperous Western Balkans region. By hosting the summit in London, we demonstrate our continued interest and involvement in the stability of the region beyond our exit from the EU.”

More fundamentally, the London-based think tank Emerging Europe noted the comments of UK-based Serbian media correspondent Siniša Lepojević:

“The Balkans, and namely those Balkan countries that are not EU members, remain the only space where the British can ‘flex their muscles,’ because they will exit the EU in March 2019. They need a presence in this part of Europe, because after Brexit, London will have nothing but NATO and the Western Balkans.”

It was intended that Boris Johnson—as foreign secretary—would announce an increase in funding to the region to £80 million in 2020-2021 and the launch of a UK package of £10 million to “build digital skills and employment prospects” for young people in the region, as part of a Global-trade Entrepreneur Programme. But his audience was left waiting.

Initially it was announced that Johnson was delayed due to an urgent meeting on the latest “Novichok” poisonings in Salisbury. It soon emerged that he was, in fact, gathered with his advisers, preparing his resignation from the cabinet over Prime Minister Theresa May’s “soft-Brexit” proposals.

In the end, despite joint declarations on “Good Neighbourly Relations, War Crimes and Missing Persons” and “Principles of Information-Exchange in the field of Law Enforcement,” little of a concrete character came out of the gathering.

The EU has committed to invest up to €150 million in 2019-2020, to help “unlock private investment in a broad range of sectors … thus tackling key bottlenecks hampering access to finance in the region.”

But there was no movement on accession. Apart from Albania, the six Western Balkan countries that now want to join the EU (Serbia, Montenegro, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Kosovo and Macedonia) emerged from the collapse of Yugoslavia, which was actively promoted by the US and European powers to secure their hegemony over the Balkans.

But, as noted previously, the regimes they helped bring to power are so corrupt and tied in with organised crime that delivering on the promise of EU membership would further destabilise the bloc.

In May, the EU-Western Balkans summit in Sofia had postponed opening membership talks with Macedonia and Albania and made no mention of EU membership or enlargement more specifically. This was despite the Greece-Macedonia deal to resolve the 25-year dispute over the latter’s name, so that the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia (FRYOM) now becomes North Macedonia.

Just days after the London summit, the EU imposed new conditions on Bulgaria’s application to join the euro, making it dependent on fulfilling extra criteria. These include passing European Central Bank stress tests and asset quality reviews of its banks before its application will even begin to be considered in July 2019. The Financial Times opined that the obstacles on Bulgaria—which joined the EU in 2007—were proof that the EU was “quietly changing its criteria for eurozone membership” out of concern for financial stability.

However, failure to integrate the west Balkan countries has opened up space in the region for Europe and Britain’s competitors. It threatens to become a gaping hole under conditions in which US President Donald Trump has thrown a hand grenade into the transatlantic alliance, making clear he favours the break-up of the EU and has even criticised NATO.

The summit debacle caused consternation in Britain’s ruling circles.

The Economist complained, “Thanks to Boris Johnson, a farcical west-Balkan summit in London” at times resembled a “Carry On movie” [a famous and much-loved series of British comedy films].

The Financial Times warned, “EU’s waning influence opens a dangerous vacuum in the Balkans,” writing that Johnson’s no-show was a “fitting metaphor” for Western European leaders’ “disinterest in the Balkans.”

Complaining that a “historic opportunity … is at risk of being lost,” it continued that it has opened “a vacuum that other powers—China and Russia—are seeking to fill.”

The FT noted that only the previous weekend, China had organised its own summit with 16 central and eastern European countries in Bulgaria, “where Beijing lavished pledges of investment,” and accused Russia of “mischief-making” in trying to thwart NATO expansion.

The seventh CEEC-China summit comes as Beijing invests heavily in the region as part of its $1 trillion Belt and Road Initiative. It has put millions into building and repairing infrastructure in Serbia—heavily damaged in NATO bombings some 20 years ago—including a $740 million highway, connecting Belgrade with Montenegro, and a $3 billion investment project for a 350km high speed rail link between Belgrade and Budapest.

China is accused of politically backing Serbia against EU/US demands that it must recognise Kosovo, while Belgrade is regarded as a Russian ally.

The Chinese company COSCO operates the Greek port of Piraeus, one of several major investments in the country that has been ravaged by EU austerity. China Everbright Group owns Tirana International Airport, in Albania, while Chinese corporations are invested in the country’s oilfields.

Poland and Hungary are also part of the 16+1 initiative, and the right-wing governments of the two countries have repeatedly clashed with the EU. Politico, writing on Trump’s denunciations of Germany—which is a target of US sanctions against the EU—cited James Carafano, of the right-wing conservative Washington-based Heritage Foundation. Carafano noted “that some countries in Eastern and Central Europe resent Germany’s influence on the continent and might take pleasure in Trump’s approach to Berlin. ‘People say “Why is he making so many enemies in Europe?” but I say, “He might be making a lot of friends in Europe”,’ Carafano said, mentioning Poland as one example.”