Tahrir Square, seven years on.

By Pierre Daum

5 March, 208

On a winter evening in Tahrir Square, young skateboarders were practicing their moves in front of the huge Soviet-style Mogamma building. Nonchalant policemen and couples of all ages watched, and nobody seemed to notice the dust and the deafening traffic, scourges of life in Cairo that no revolution has ever swept away.

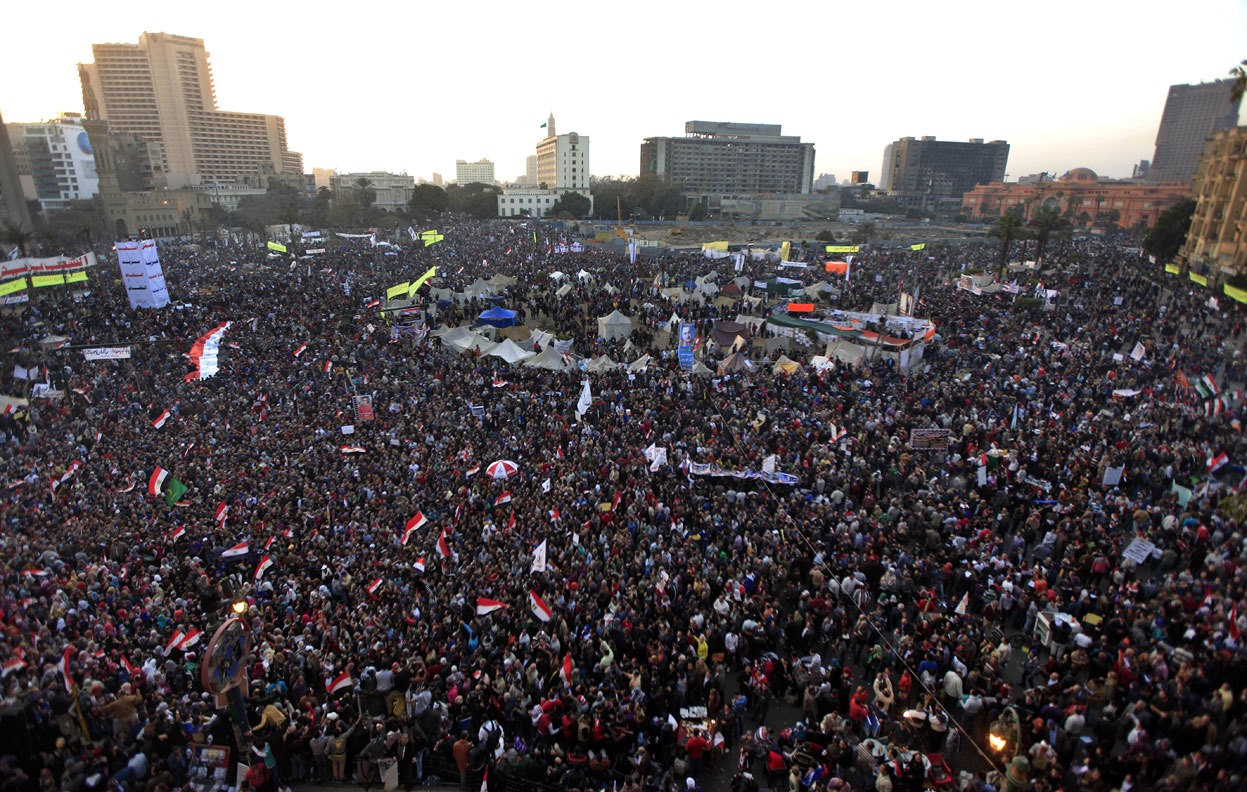

It felt like a long time since 2011, when hundreds of thousands of Egyptians crowded into this vast square in the “January revolution,” demanding the overthrow of Hosni Mubarak’s regime and “Bread, freedom, and social justice!” In 2013, at least as many gathered again in Tahrir to call for the departure of the Muslim Brotherhood’s Mohamed Morsi, whom they had democratically elected president; in a military coup backed by a section of Egyptian society, the army regained control on June 30 of that year. A fledgling pro-Morsi resistance was crushed, and around 1,000 people died, on August 14 in Cairo’s Rabaa Square. Thousands of arrests followed. In June 2014, Marshal Abdel Fattah al-Sisi became president with 97 percent of the vote.

Since then, life for most Egyptians seems, at first glance, no worse than before. Cafés are still full of people smoking shishas, watching football, and chatting. Men and women meet in bars for a beer. There are films and concerts, and contemporary art at Townhouse, a superb exhibition space in a former paper factory near Tahrir.

There is no reminder in the square that it was where Egyptians demanded the fall of two presidents. The avenues that radiate from Tahrir are orderly and clean, and the interior ministry, the object of much revolutionary hatred, has been relocated to a distant suburb. Apart from a few traffic officers, there is little visible police presence. Yet last autumn Amnesty International severely criticized Egypt’s political climate: “The authorities severely restricted the rights to freedoms of expression, association and peaceful assembly in law and practice. Journalists, activists and others faced arrest, prosecution and imprisonment on charges that included inciting or participating in protests, disseminating ‘false rumours,’ defaming officials and damaging morality.”

“I think Sisi’s doing his best”

I met Miran, 30, and her friends near the square. She said: “Do I feel like I live in a dictatorship? No, not really.” She comes from a middle-class family, her father is an engineer, and took part in the 2011 revolution—“of course”—and the 2013 demonstrations. “My mother is absolutely behind Sisi. She loves him. My father’s more critical. He thinks Sisi can’t run the economy and since he’s been in power the cost of living has risen. I’m in the middle. I don’t love him, but I think he inherited a terrible economic situation and is doing his best.”

Was she shocked by government repression and detentions? “Yes, a bit. But some of those people are terrorists. And Sisi must know what he’s doing. When things get better, he’ll free them.” Miran and her friends talk openly about politics in public places. “Even on Facebook I don’t worry about criticizing the government and even the president. I’ve not had any trouble.” Her friend Ahmed said: “The real question is money, not freedom. Everybody’s suffering from the economic crisis now.”

Beyond impressions from chance encounters, it is hard to know what Egyptians really think about a regime that does all it can to discourage protest. In January, as a warning to opposition figures and parties calling for a boycott of the presidential election scheduled for March, Sisi said that “people who understand nothing about the state want to intervene and make pronouncements. This is unacceptable.” Opponents call this election an absurd comedy because many of Sisi’s rivals have been arrested, forced to withdraw, or disbarred from standing. Sisi insists: “We are guaranteeing stability and security, otherwise there would be collapse. I am not threatening anyone. What happened seven years ago will not be repeated in Egypt.”

The political climate has been marked by the military’s return in force to all branches of power, particularly the economy. Political scientist Tewfik Aclimandos of Cairo University said: “The army has long had a positive image. Rightly or wrongly, it’s considered less corrupt than the police, more efficient that the civil service, and it presents itself as a manifestation of the people. Everyone in Egypt knows someone in the army.” As for what the people think of the president, “it’s forbidden to do real polling about that. We have to extrapolate from signs of optimism. From those, it seems almost certain that the enthusiasm that carried Sisi to power in 2013-14 has declined considerably, especially since the attack on the Russian plane in 2015. But he still has a solid base.”

“I try not to self-censor”

To help sustain popularity, the regime controls the media, especially broadcasting. Under Mubarak and after the revolution, private television channels started up, which broadcast popular talk shows with genuine debate; those have all disappeared. Now every channel is run by the regime or its cronies, as is the press, with the possible exception of Al-Masry Al-Youm, a daily with a print-run of 120,000 (in a country of over 100 million). Doaa Eladl, one of its star cartoonists, said: “It’s true that we’re independent. But there are red lines—blurred ones—that make my job harder. Any topic at all can anger the regime. I try not to self-censor, but I’m sure I do…. I have a deeper problem. As soon as a subject becomes too sensitive, every paper, even ours, stops talking about it.” The president can’t be shown in a cartoon, but last November the paper printed one of young Egyptians in prison to coincide with Sisi’s opening the Sharm El-Sheikh World Youth Forum.

Censorship has enabled the authorities to spread paranoid fear of foreign spies. Khaled Al Khamissi, author of the story collection Taxi (2007), said: “On TV and in the press there’s always a regime loyalist to explain that the US and its European allies supported Egyptian civil society in overthrowing Mubarak. Or that an American-Zionist plot is trying to give part of Sinai to the Palestinians. But that fortunately President Sisi has managed to foil these plots and save Egypt.” This policy is working: A passenger told me to stop taking photos from a bus window “because of national security.”

In such a context, space for dissent is extremely limited. Egyptian human-rights organizations believe there may be as many as 60,000 political prisoners, but there are no reliable figures. Many people have been arrested and released on bail. Most have links with the Muslim Brotherhood or are suspected of being pro-Morsi or activists from the revolutionary camp. Egyptian Coordination for Rights and Freedoms (ECRF) has recorded around 40 forced disappearances a month.

The Muslim Brotherhood, the only opposition force for decades, has been eradicated from the political landscape through repression and by deep internal conflicts. Several thousand members have fled to Turkey. Fatiha Amal Abbassi, who is writing a thesis on the Brotherhood, said: “Those who have stayed, if they’re not locked up, live like ghosts. They’ve changed the way they dress and speak, and the usra, the weekly meeting that members were supposed to attend, has been suspended. Many of them completely disagree with their leaders and have distanced themselves from the organization.” Some may have joined terrorist organizations, but no corroboration is possible: The authorities class every opponent as a terrorist.

“We’ll keep going until death”

As for the activists who drove the 2011 revolution—“initially a group of a few thousand people,” according to French-Egyptian political scientist Youssef El-Chazli, “around whom tens of thousands of sympathizers gathered without ever constituting an organization or party”—most of them are no longer politically active. Some are in prison, other have gone abroad. Many have experienced depression. Mansoura Ez-Eldin, novelist and journalist at Akhbar Al-Adab, said: “It’s very painful having taken part in something as significant as the revolution and having had such dreams of changing your country, to find yourself experiencing your own defeat. I’ve survived by reading, writing and focusing on the little things in my life. I moved with my husband and children to New Cairo, outside the city. There I felt as though I was living in a place far removed from Tahrir.”

A few former revolutionaries continue their activities in human rights NGOs. Malek Adly heads a lawyers’ network, the Egyptian Centre for Economic and Social Rights, and spent four months in prison in 2016. Now, he said: “We’re harassed by the police. Most of us aren’t allowed to leave the country. We have trials pending for receiving funds from abroad or ‘harming state security.’ We may face decades in prison, but we keep going. We’ll keep going until death if necessary.”

The ban on receiving funds from abroad, which the authorities justify on the grounds of combating foreign interference, is an effective way to destroy activist organizations. (It also affects the cultural sphere. As the culture ministry does not award grants, cultural organization relied on Western support.) In May 2017, a new law on NGOs was passed, which may mean the end for the last survivors. It prohibits foreign funding, and each NGO must now present a registration-renewal request before a commission in which the military participate.

Esraa Abdel Fattah, the revolution’s “Facebook Girl,” feels disillusioned: “I lived through those 18 days in 2011”—from January 25 to February 11, when Mubarak resigned—“like a wonderful utopia. But we were idiots—idiots to believe Morsi’s promises of democracy. Sometimes I think there’s no hope and Sisi will stay forever. But if I stopped my activism I’d feel I was betraying everyone who’s died or gone to prison.”

But Sisi’s apparently omnipotent regime has a deep fear of the people, despite having tamed the media and devastated the opposition. Karima, a political scientist, said: “The regime is doing all it can to contain the possibility of any social stirring, as though it dreads ‘another Tahrir.’” All demonstrations or gatherings are strictly forbidden. On the pretext of terrorist threats, four-meter-high concrete walls have been erected around all ministries and the central bank and armed soldiers protect entrances. Every Friday, when demonstrations traditionally take place, policemen in riot gear are posted on the seven main roads leading to Tahrir Square, and anti-riot trucks stand by.

“The situation’s so disgusting”

In the past two years, only two demonstrations have been permitted in Cairo, both outside the center: one against the transfer of uninhabited islands in the Red Sea—Tiran and Sanafir—to Saudi Arabia in April 2016; the other against Donald Trump’s decision to recognize Jerusalem as Israel’s capital in December 2017, a decision criticized by all Egyptians, who remain sensitive about the Palestinian question. Towards the end of that demonstration, some protesters shouted “Bread! Freedom! Social justice!” and their ringleaders were later imprisoned. In February, 17 people were sentenced to life imprisonment for demonstrating against Sisi during the 2014 presidential election.

Strangers I approached in public places were unwilling to criticize the regime. I met Mahmoud near his home in Ain Shams, a desperately poor district an hour’s drive from Tahrir Square. He took part in the 2011 demonstrations, and is unemployed. “I can’t stop myself talking, starting discussions in local cafés. The situation’s so disgusting. Everyone’s sick with hunger, there’s no freedom. But three days ago friends told me plainclothes police had been asking about me. I have another friend this happened to and he’s in prison now. It’s a warning. I’m going to stop talking to people.”

Warnings like this are a way of suppressing any appetite for rebellion. Many interviewees asked me not to write down things “or I’ll risk jail.” The warning in the universities was the death, in unexplained circumstances in January 2016, of Italian researcher Giulio Regeni. According to Reuters, he was arrested on the street by plainclothes police and taken to a Cairo police station before vanishing. His mutilated body was later discovered. The authorities put forward a number of unconvincing theories, such as a kidnapping that went wrong or a sex crime. One French researcher told me: “Whether it was a mistake or a targeted killing, we’ve all become very careful.” His research into Egyptian public opinion is now conducted secretly.