Radhika Desai

Professor at the Department of Political Studies and Director, Geopolitical Economy Research Group, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, Canada

The 25th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall finds Eastern Europe at the centre of a new crisis and a new confrontation between West and East. Events of a quarter century ago concerned the end of Soviet and East European non-capitalist systems. The events of our own time, I would argue, are raising equally grave questions about the future of capitalism.

While the western, particularly the English-speaking, media has a field day blaming Putin for the crisis and demonizing him as an annexationist aggressor, more careful observers can clearly see that one of the key causes of the crisis is western expansionism whose battering rams in the Ukrainian case have been NATO and the EU.

While Putin is certainly no angel, a focus on individual personalities draws attention away from the larger historical forces at work. I would like to refocus attention on them by recalling another, arguably more fundamental, anniversary we marked last year. I don’t mean that of the First World War, important though it was as the culmination of competitive imperialism and for birthing the historic Russian Revolution. I refer instead to what the noted historian, Arno Mayer, called the ‘Thirty Years’ Crisis’ of 1914-1945. This single prolonged period of crisis included the two World Wars and the Great Depression. It also birthed a new order: the world that went into it was authoritarian, imperial and weighted against the interests of working people, workers as well as peasants. The one that emerged from it was, while hardly a paradise, one of formal liberal democracy in welfare states, the Soviet and other non-capitalist systems and decolonization. It was also one in which, thanks to the historic struggles of working class, peasant, nationalist and communist movements, was also in which their interests counted for more.

The developments that resulted in the outbreak of the Thirty Years’ Crisis were memorably analysed by a brilliant constellation of Marxist theorists of whom Rosa Luxemburg, whom tomorrow’s demonstration will commemorate, was perhaps the foremost and most radical. The penetration and veracity of their analyses came precisely from their ability to focus on the deeper historical forces at work in the situation. Contemporary developments deserve similarly weighty analysis and today I would like to make a small contribution to that effort by reflecting on what seem to me some of the main lines of such analysis.

Perhaps the best place to start is with the designation of current events as a ‘new Cold War’ by many important observes, including former Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev. They see western, EU and NATO expansionism as a key factor in the crisis. Certainly, since the end of the old Cold War, rather than being disbanded as would have been expected if the sole purpose of NATO had been to combat so-called Communism, NATO has expanded far beyond its original Atlantic base. Over the past quarter century, it has acquired members, partners, bases and operations on every continent. On the European landmass, at least, the EU has often followed NATO expansion. Moreover, tensions between the West and Russia may be the most acute at this time but they are not isolated: they are matched by others between the West (and Japan) on the one hand and China and the BRIC and other emerging economies, Cuba and the numerous ‘Bolivarian’ left-of-centre governments of South America it has inspired, not to mention Islamist Iran and radical Arab regimes on the other.

The idea of a ‘new Cold War’ is suggestive and accurate in many ways, particularly given that Russia is a key target and that the dangers, threats and fears it conjures up are equally dire. It even led some of us to create a website with that name to provide more accurate information on the Ukraine crisis not easily available in English at www.newcoldwar.org. However, that designation can be misleading in at least five important ways and exploring and correcting them is a good way to understand our times much better.

I

Firstly, if the Cold War was a contest between capitalism and what the west demonized as communism, why should a new Cold War break out after Russia has turned capitalist?

In attempting to explain this, writers turn to conventional ‘geopolitical’ writing, such as those, for instance, of the English scholar Halford Mackinder and the Americans, Nicholas Spykman and Alfred Mahan – Germany had its own Carl Schmitt and Karl Haushofer – who all identified the Eurasian landmass as, in Mackinder’s words, the ‘geographical pivot of history’, to be controlled by any power which seeks to dominate the world.

That those who seek to direct US strategy, from Samuel Huntington to Zbigniew Brzezinski, find it politic to resort to such ideas should alert the rest of us to their fundamentally ideological character. As Lenin was clear, classical and historical allusions by capitalist powers simply serve to mask the specifically capitalist character of modern imperialism. That cannot be understood without putting an understanding of capitalism at its centre, as Rosa Luxemburg did, for instance. She and her fellow theorists of the competitive imperialism of their time understood that capitalism suffers from contradictions and that, therefore, capitalist states must attempt to manage them: when the ‘invisible hand’ of the market shakes, the visible hand of the state must steady the system. In our own time this was made blindingly clear as capitalist states bailed out the financial institutions that caused the 2008 and 2010 financial crises and imposed its costs on working people.

However, capitalist states attempt to do this not just by managing the domestic national economy. To an equal if not greater extent, they have to try to achieve this by managing their international relations to confer advantages on national capitalist classes against the capitalist classes of other nations and by externalizing the costs of domestic contradictions, as far as is possible given the international balance of forces, on less powerful states. Such international actions have historically included colonial control over weaker states and societies in particular. That formal colonialism is no longer an option for the dominant states is a mark of the long distance the world has travelled in the last century. It also means that capitalism’s contradictions must be resolved in new ways, as we shall see.

This means that what makes a state capitalist is not that it does not intervene in the economy, leaving it to private activity in markets, but that, on balance, it intervenes in favour of capitalist classes to the extent the domestic and international balance of forces allows. This point will become important later.

The first reason why contemporary developments should not be understood as a new Cold War is that the label refers to a confrontation between capitalism and its non-capitalist rivals and diverts attention from more fundamental drivers of the relations between states in a capitalist world. We must instead place capitalist expansionism, including that of NATO and the EU, in a conception of capitalism and its inevitable contradictions, and of the challenge represented by Russia, China, the idea of Eurasianism, the BRICs and an array of other forces. This leads us to recall, with fresh relevance, the role that the challenge to British dominance of the state-led combined development of the US, Germany and Japan, played, in the events leading up to the outbreak of the Great War in 1914.

II

Thus the second way in which the designation of current developments as ‘new Cold War’ is misleading is that it misses the much longer continuity in the international purposes and policies of the major capitalist states. As I argue in my recent book, Geopolitical Economy: After US Hegemony, Globalization and Empire, the Cold War between capitalism and so-called communism was part, albeit a very important part, of a longer and wider dialectic of uneven and combined development (UCD). It in, on the one hand, capitalist imperialism sought to maintain a given world configuration of uneven development. On the other hand, other, less powerful states engaged in that combined development through which wave upon wave of contender developers since the first wave which included the US itself, Germany and Japan in the 1870s, challenged that configuration of uneven development. Because of the need, mentioned earlier, of capitalist states to attempt to resolve the manifold contradictions of capitalism through international actions as well as domestic ones, and others to challenge them, the dialectic of UCD has a history as long as that of capitalism itself. Indeed, its dialectic drives the capitalist world’s international relations much as class struggle drives domestic politics.

UCD can be briefly outlined. It is clear to most that capitalism’s contradictory and exploitative character creates new structures of class inequality within societies. It is less widely appreciated that the same character also creates new structures of international inequality between them. Dominant nations seek to advantage their capitalist classes and to inflict the consequences of the contradictory development of capitalism within them, particularly its demand constraint, on weaker states and territories over which they exercise formal or informal imperial control. These forms of control also help reinforce and maintain their privileged positions in the structures of such ‘uneven development’. While these actions are correctly understood as imperialism, it is important avoid the tendency to assume that it is a constant and unchanging structure.

The chief flaw in such an assumption is that other nations do not gladly suffer such dominance, or the threat thereof. They seek to challenge it through ‘combined development’, hothousing industrial development through state direction, to the extent they can. While the goal of the former is to maintain complementarity between their economies and those they are able to dominate, for example by consigning them to be markets for industrial products and suppliers of cheap raw materials or labour, the latter reject this role and seek, instead, similarity, particularly in terms of levels of industrial and technological development.

While not all weaker states and territories are capable of or inclined towards mounting such efforts at ‘combined’ or contender development, and while not all those who mount them are equally successful, the unfolding of this dialectic of international dominance and resistance, of uneven and combined development has, so far at least, been resolved in favour of the latter trend. Each wave of combined development, by spreading productive power more widely and leaving a more numerous group of successful developers competing with each other has made the next wave of combined development a little easier. The contemporary contender development of China and the other BRICS and other emerging economies is just the latest phase of a series of waves of such contender development going back to that of the US, Germany and Japan against UK dominance in the late 19th century.

Combined development could take both capitalist and, as became clear after 1917, non-capitalist forms. The Cold War was, therefore, only the strongest form of confrontation between states seeking to preserve the imperial order and their privileged positions in it, and others resisting them. Many of the most perceptive analysts of the Cold War had pointed out even at its height that the Cold War was directed as much against ‘communism’ as it was against independent national development. Even today, it is the challenge of Communist Party-ruled China that remains the strongest of the challenges that the established capitalist powers face while that of Russia, in particular its control over a vast nuclear arsenal, is importantly a legacy of Soviet days.

Such a geopolitical economy of capitalism’s international relations makes the tussle between the West and Russia over Ukraine, and between the Atlanticist and Eurasian options before Ukraine, more intelligible. In it the West seeks to subordinate Ukraine to its own imperatives, to turn it, as it has turned other countries of Eastern Europe which have mostly been incorporated into the EU on second class terms, into a labour reserve for Western Europe and a market for its goods after destroying what remains of their productive capacity. That is why the more industrial Eastern Ukraine fears the Atlanticist option. All this comes, of course, wrapped in the slick allure of the much hyped democracy and prosperity of the West. It only serves, however, to hide its enervated capitalism and hollowed-out democracy. The path offered by Russia is not only less slickly packaged, it is much less clear and certainly not guaranteed to succeed. But for any society seeking to develop productively, it could be the more attractive option to subordination to stagnant and speculative West European capital: one of joining a contender pole of development which would align it with the more fast growing economies of eastern Asia.

III

A third way in which the designation the ‘new Cold War’ is misleading is that it revives the idea of US leadership of, or ‘hegemony’ over, the capitalist world. The dialectic of UCD, which forms the core of the geopolitical economy of the capitalist world order, sheds entirely new light on the US role in 20th century world affairs. The dominant conception is that it was a ‘reluctant hegemon’. In fact, it was neither reluctant nor hegemonic. An expansionist republic from its earliest beginnings, the US completed its continental expansion by the 1890s. Thereafter it came to nurse the greater ambition of replacing declining UK dominance over the world economy with its own. As Geopolitical Economy shows, Hegemony Stability Theory is little more than an elaborate ruse for this desire, emanating from the figures closely connected with the highest US policy-making circles, such as Charles Kindleberger.

Unfortunately for the US, the very configuration of the combined development that ended UK dominance would frustrate its ambitions. It was inevitable that, as the first industrialiser, the UK would dominate the world economy for a time. But it also prompted the contender industrialization of a plurality of rival powers. That the contender challenge came from a plurality of rival powers including the US itself, Germany and Japan, meant that by about 1870 the world had already become multipolar. UK dominance may have been inevitable: it had also become unrepeatable.

Lenin may not have been entirely right to insist that inter-capitalist competition must lead to war and that there was no possibility of cooperation between capitalist powers as Kautsky’s ‘ultra-imperialism’ thesis claimed. Lenin changed his mind about this later anyway. However, there was a rational kernel in both positions. Some inter-capitalist cooperation could not be ruled out, especially against the threat of communism as in the postwar period. However, those who claim that Kautsky was proved right by the postwar experience were ignoring the inter-capitalist tensions that continued despite the Soviet threat and drove developments, as we see below. So, perhaps the key point to take away here is that a stable capitalist world order is not possible.

The already multipolar realities of 20th century tempered US ambitions, scaling them down. A formal empire being out of the question, the US settled for trying to make the dollar the world’s currency, replacing Sterling, and New York the world’s financial centre, replacing London.

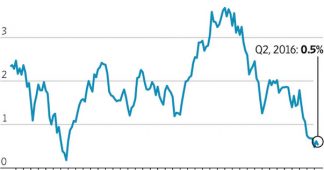

Even this scaled down ambition would not be realized. Though the Second World War boosted the US economy precisely as it laid other major economies to waste, and though it gave the US that famed but momentary dominance at its end, the dollar never became the world’s currency in a stable way. Its career is the story of a series of failures – the dollar shortage of the 1950s, the dollar glut of the 1960s, the closing of the gold window in 1971 and the series of financializations – the debt bubble of the 1970s, the US twin deficits financed mainly by Japan in the 1980s, the stock market bubble of the 1990s and the credit/housing bubbles of the 2000s – that became necessary to support the dollar’s increasingly unviable world role after 1971. After the mother of them all burst in 2008, international capital flows collapsed and have yet to recover to a point which can sustain prevent the dollar’s world role from diminishing. Moreover, if they did, they would subject the world to the sorts of volatility which the rest of the world is unlikely to put up with and to which it is already building alternatives.

To these monetary failures corresponded a long record of military failures – from Korea and Vietnam to the ‘quagmires’ of Afghanistan and Iraq. What unites them both is the empty hubris which has led the US to attempt an impossible dominance. It never succeeded in the enterprise but did inflict great costs in terms of lives and livelihoods on the world. Moreover, in pursuit of this ambition, the US prevented the creation of alternative institutions of world economic and political governance which could have been more multilateral, more politically stable and more viable.

But if global solutions were prevented, regional ones were not.

In a practical demonstration of the real limits of US ‘leadership’ and ‘hegemony’, the US’s closest allies, the Europeans, were in the forefront of easing the dollar out of their mutual transactions with the launch of the ‘Snake’ in the early 1970s and culminating in the Euro in the 2000s. The problems of its internal governance revealed by the recent Eurozone crises notwithstanding, it was successful in achieving this broader geopolitical economic goal and, in doing so, has blazed the trail for other contender powers to follow suit – whether it is the Russians and the Indians agreeing to trade in one another’s currencies or the participation of China and other major Asian economies in the Chiang Mai Initiative, or the various left-of-centre regimes of South America making alternative monetary and economic arrangements, not to mention the New Development Bank and the Contingency Reserve Fund announced at the last BRICS Summit in Forteleza, Brazil.

In the wake of the financial crisis the US record has become, if anything, even less successful and more hubristic and incoherent. US military spending, astronomically high as it has long been, was never unlimited. After all, US overspending on Vietnam was what first alienated European authorities from the dollar system and as early as 1991 the US was seeking to re-distribute the financial burdens of the first Gulf War to its so rag-tag bunch of allies. Recent crises have, however, reduced the US ability to support and sustain the scale of military operations its global ambitions would require even further, imposing the first major reduction in the US military budget this century. The most recent round of cuts has led, for instance, to the closing of 15 bases in Europe.

If the extent of US military operations is being squeezed, their nature has also long compromised the possibilities of US success. Having forsworn the military draft after the domestic disasters of the Vietnam war, the US had inclined towards what we may call more capital-intensive warfare – from aerial ‘precision’ bombing to drone warfare. But these have yielded no major successes to the US and, with their intolerable levels of ‘collateral damage’ inflicted on civilians, have earned it more enemies of which the Islamic State is only the latest.

It is apparent to many that US policy against the IS – a combination of shrill rhetoric unsupported by any effective actions – is incoherent. Some explain this as the outcome of the bureaucratic imperatives of the US’s vast defense bureaucracy. There is also the long-standing explanation, which aligns with Rosa Luxemburg’s key thesis about the utility of military expenditure in capitalist economies, especially when they are stagnant and suffering from chronic demand deficits, that the US’s permanent war economy has created imperatives of its own. Certainly it is plausible that the country’s dysfunctional political system is unable to produce the sort of leadership that would be required to acknowledge that attempts to pursue the US’s goals of global dominance are today less likely to achieve meaningful success of any kind than they ever were.

Certainly US and western control over world events is not what it used to be. The western failure, despite much posturing and sabre-rattling, to prevent Crimea’s accession to Russia is only the latest in a series which includes confrontations over Georgia and the necessity to impose sanctions selectively. Cracks are also beginning to appear in NATO and the Atlantic alliance more generally with the more confrontationist English-speaking countries and the more careful and conciliatory Germans in the case of policy over Russia and Ukraine or with Turkey over the stance on the Islamic State. At the same time, US policy also pushes the contender closer together, as, pre-eminently in the case of China and Russia’s recent gas and currency deals.

IV

The fourth way in which the label new Cold War can be misleading is that it drags into our discussion that old ideological baggage of the superiority of the capitalist west over the Soviet system precisely when the limitations of the capitalist system are on display to an historically unprecedented extent. It was never, in any case, true that the US and the West had somehow ‘won’ the Cold War’. In fact the non-capitalist systems of the USSR and Eastern Europe ended largely because their leaderships permitted them to end, having lost faith in the originally anti-capitalist mission. When it happened, advanced capitalist economies were already suffering a two-decade long growth slowdown that the New Right leaders, who took power after the intense class struggles of the 1970s and loved taking credit for the events of 1989 and 1991, proved singularly unable to solve.

The triumph of the New Right ensured that governments in the advanced capitalist world would attempt to resolve the crisis on capitalist terms. After three decades of trying, the 2008 and 2010 crises are all they have to show for it. Not only did they fail to restore growth to the levels that capitalism had enjoyed in its ‘golden age’, such growth as was achieved suffered from two further defects. First, during the ‘golden age’ the world economy had grown in a largely synchronized fashion. Though the main growth story that of the recovering and developing economies, they were so numerous as to give the growth pattern a very broad base. During the neoliberal era after 1980, growth in one part of the advanced industrial world occurred at the expense of the others while large parts of the developing world suffered retardation under the two ‘lost decades of development’ of the 1980s and 1990s under IMF and World Bank imposed ‘Structural Adjustment Programmes’. Secondly, while the growth of the golden age was based securely on productive expansion, that of the neoliberal era became reliant on the blowing up of asset bubbles of which the US-centered housing and credit bubble that burst in 2008 and the various smaller ones that burst around Europe after 2010 were the most recent examples.

It is no surprise, therefore, that the alleged ‘victor’ of the Cold War, President George Bush Jr, lost the US Presidential Election primarily because of the debility of the US economy – as Clinton’s campaign manager put it when asked to explain the Clinton victory, ‘it’s the economy stupid!’ – that election also featured the most successful third candidate, a businessman who ran on a platform of the need to revive the US economy and rescue it from competition from its own alleged ‘allies’, pre-eminently Japan.

The ability of capitalism in these parts of the world to yield acceptable levels of productive growth is now exhausted. This is what is behind the interminable discussions of ‘monetary policy’. As I have argued elsewhere, the real purpose of all this talk about this or that technicality of monetary policy, the real reason why it is ostensibly geared to levels of economic activity and employment when the real intention, hidden from no one, really, is to ensure adequate liquidity for the very financial institutions that caused the crisis so that they can continue the only form of profit-making they are capable of now, speculation, is that the alternative of fiscal policy, if engaged to the extent necessary to restart growth would amount to government intervention of such a massive scale as to displace capitalists from the driving seat of the economy and raise fundamental questions about their utility and that of an economy run by them, i.e. a capitalist economy.

V

This brings us to the final reason why the language of the Cold War hides more than it reveals. For difference between capitalism and the Soviet and other non-capitalist systems we have known hitherto was never about market versus planning. The state has always played a central role in both, only in the first, it was committed to creating and maintaining an economy in which the capitalist class remained in the driving seat. As long as this arrangement delivered adequate levels of growth, it retained a measure of legitimacy. Today, however, when it cannot, the question of why the state should act to reinforce the power and control of the capitalist class over the economy has finally become an urgent one.

As has been clear from the beginning of this century, with slow growth plaguing the advanced industrial world already, the fastest growing countries were those engaging in non-capitalist (as, arguably, still in China given that, despite the existence of a substantial and obscenely rich capitalist class the Communist Party retains control of the state) or capitalist combined development (as in the rest of the BRICs and emerging economies). And the crisis has revealed an enervated capitalism which is less and less an example or alternative to the rest of the world.

Rosa Luxemburg Conference in January 2015