By Nick Beams

24 October 2017

A warning by the governor of the People’s Bank of China, Zhou Xiaochuan, that the country’s financial system faces a possible “Minsky moment” has again raised concerns over the level of the country’s debt.

Zhou, who is expected to retire soon from his position as head of the central bank, made his remarks at a sideline meeting during the Chinese Communist Party congress last week.

The term “Minsky moment” refers to a situation described by the US economist Hyman Minsky in which growth in the economy hides potential financial risks that suddenly reveal themselves and lead to a crisis. It was widely used during the 2008 global financial crisis.

Zhou clearly employed the term to ensure his comments would have maximum impact. Zhou, who has said he will “retire soon,” has been speaking increasingly candidly about the problems confronting the Chinese economy.

Zhou said asset speculation and property bubbles could pose a “systemic financial risk” that would be made worse by wealth management products and off-the-books lending. Corporate debt had reached disturbingly high levels and local governments were using tricks to evade curbs on their credit.

“If there is too much pro-cyclical stimulus in an economy, fluctuations will be hugely amplified,” Zhou stated. “Too much exuberance when things are going well causes tensions to build up. That could lead to a sharp correction, and eventually to a so-called Minsky moment. That’s what we really must guard against.”

Zhou’s remarks are particularly significant. In general commentary on the state of the Chinese economy, the prospect of a full-blown crisis is often ruled out because the banks are under government control. This control has been undermined, however, by “free market” measures introduced by the regime as it seeks to integrate the Chinese economy and financial system more deeply into the global economy.

Zhou himself has been an advocate for greater liberalisation of the Chinese financial system, including the relaxation of government controls on capital movements and increased access for foreign banks, but has faced opposition within government circles.

Zhou was the main force behind the push to have the International Monetary Fund (IMF) recognise the renminbi as an international currency last year. Without the freedom of movement of capital in and out of the financial system, however, it does not have the status of other reserve currencies.

Free capital movement is a two-edged sword. On the one hand it is seen as applying pressure to domestic financial institutions, forcing them to deal with bad debt on their balance sheets. On the other, it runs the risk of creating the conditions for a major outflow of capital, as was seen in the Asian financial crisis of 20 years ago, an occurrence which would have a major impact on the Chinese economy.

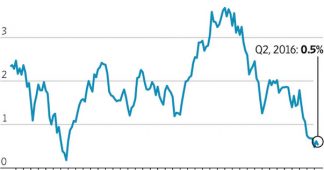

Zhou’s warnings came as the growth rate for the third quarter was reported to be 6.8 percent on an annual basis, well above the government’s target of “around” 6.5 percent. But there are concerns that this higher growth rate has been achieved largely as a result of stimulus measures, relying on the expansion of credit, particularly in the property market, which is creating risks for the future.

Eswar Prasad, economics professor at Cornell University and former head of the China department at the IMF, said the latest growth data painted a “reassuring” picture of an economy that “on the surface, is firing well on all cylinders. But beneath the surface, potential financial market stresses continue to build up but remain at bay for now.”

If growth continues at the current level, China will experience its first acceleration in growth since 2010. At that time, the economy expanded rapidly due to stimulus measures—increased government spending and credit—adopted in response to the global financial crisis, which resulted in the loss of around 23 million jobs.

In his remarks last week, Zhou said corporate debt was “very high” and household debt, while still low, was rising rapidly. While there were no plans to reduce household debt, its quality would need to be monitored as it grew.

The IMF has issued several warnings about the high level of Chinese corporate debt, describing it as “dangerous.” Last August, it expected China’s total non-financial debt to rise to almost 300 percent of gross domestic production by 2022, up from 242 percent last year.

Last month, the S&P global ratings agency cut China’s sovereign credit rating, following a similar decision by Moody’s in May. The Chinese finance ministry claimed the S&P downgrade was the “wrong decision.”

The concerns over the financial system centre on the property market, which is assuming ever-greater significance for the Chinese economy and the banking system. According to official data, 38 percent of all bank loans in the year to August were for home mortgages, while local government bought 18 percent of all residential floor space.

Last August, a senior government legislator warned of the effects of the property boom.

Yin Zhongqing, deputy director of the National People’s Congress finance and economics committee, said in a speech: “The real estate industry’s excessive prosperity has not only kidnapped local governments but also kidnapped financial institutions—restraining and even harming the development of the real economy, inflating asset bubbles and accumulating debt risk. The biggest problem currently facing the country is how to reduce reliance on real estate.”

Zhou’s remarks underscore this warning. Financial Times market columnist John Authers described them as a “startling moment of clarity,” likening them to shouting “fire” in a crowded theatre. He said the term “Minsky moment” should never be used by a central banker.

Authers pointed to the timing of Zhou’s comments to coincide with the CCP congress. The installation of President Xi Jinping and his supporters for another five years could be the optimum time to take uncomfortable measures that could allow China to avoid a debt unravelling “to match the Lehman crisis.” The invocation of Minsky “was the earliest possible point to send the signal, and a sign of urgency.”