- Opinion

Negotiating a clear boundary between Australia and East Timor would help heal this damaged relationship and give us a stronger moral voice on global disputes, writes Damien Kingsbury.

- ABC – By Damien Kingsbury *

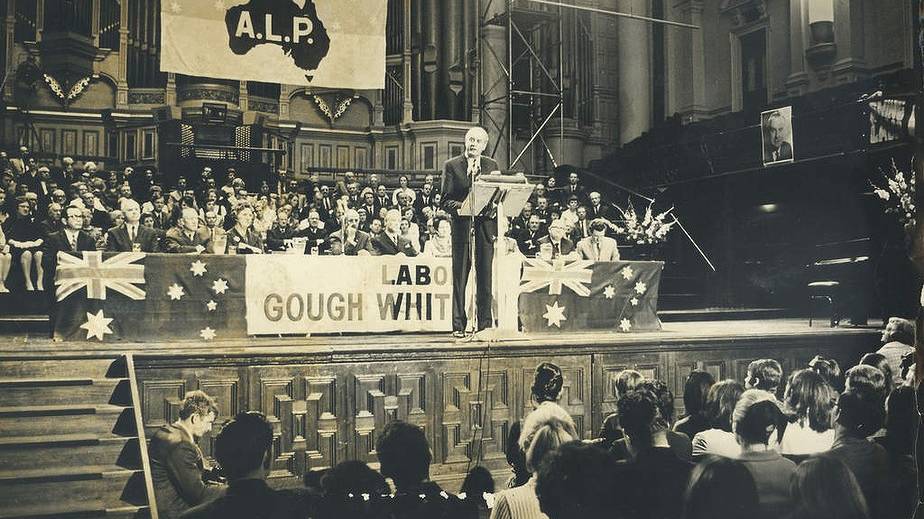

The Timor Sea issue is back on the national agenda following the announcement on Wednesday by shadow foreign minister Tanya Plibersek that Labor will, in government, scrap the existing Timor Sea Treaty.

She said that Labor would enter into new negotiations on a permanent boundary between Australia and East Timor and, if a negotiated settlement could not be reached, a Labor government would submit itself to the jurisdiction of an international tribunal.

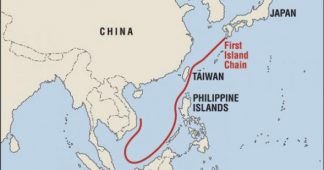

This announcement is important because it standardises Australia’s position on a rules-based international order. This is particularly important as China continues to defy world opinion by building artificial islands in disputed waters in the South China Sea.

By claiming these artificial islands as part of its national territory, China extends its sovereignty across a significant swathe of resource-rich and strategically critical sea lanes. Yet Australia’s argument that China submit to a rules-based international system for adjudication of this issue is undercut by its failure to follow such a policy when it comes to East Timor.

As importantly, re-negotiating this issue goes some way towards righting what many regard as a profound wrong having been committed to East Timor when it was at its most vulnerable. In 2002, Australia offered East Timor the alternative of signing an unfair treaty or, in effect, losing access to virtually all independent income.

That Australia did so by allegedly employing spies to bug the East Timorese cabinet rooms only made that wretched agreement more distasteful. East Timor’s former prime minister Xanana Gusmao has railed against this alleged Australian spying, yet the spying allegation was simply a means to delegitimise the 2002 agreement and establish a case for new negotiations.

While Labor has committed to entering into new negotiations, it is not clear that the Coalition government is intending to shift its position. But, apart from the Government’s weakness in arguing for international rules-based claims regarding China, it also exposes Australia to another strategic vulnerability.

If China’s activities in the South China Sea are of concern, a Chinese foothold closer to home would raise alarm. China’s ‘soft diplomacy’ approach has led to a firm relationship with the government of Timor-Leste. It is, therefore, in Australia’s strategic interest to not push East Timor further into the arms of a country which can quickly turn ‘soft’ diplomacy to ‘hard’ real politik.

Negotiating a new boundary with East Timor will require the cooperation of Indonesia, given that a boundary change could impact upon the margins of the Indonesian sea border. Some, too, will argue that there will be an economic cost to Australia.

Yet the Timor Sea oil fields are now coming towards the end of their producing lives and East Timor has benefited from the greater allocation of income from those fields in any case.

The Greater Sunrise liquid natural gas field has been seen as the biggest prize in such proposed negotiations. Once valued at potentially over $40 billion, between contractual problems, disputes over processing and now the plummeting price of LNG, the Greater Sunrise development is now very unlikely to proceed, at least within the foreseeable future. There is no income lost if there is no income generated.

East Timor had hopes of building a petro-chemical industry on the back of Timor Sea resources; that grand vision is starting to look less likely. But a formal boundary between Australia and East Timor will provide much greater certainty to Australia’s small neighbour over what resources it might have, and what it does with them.

It is reasonable that countries desire clear borders with their neighbours, and East Timor has long asked for such a border with Australia. That at least part of the Australian polity has taken a step closer to agreement on that is a step towards the normalisation of regional relations.

Such a move will improve Australia’s damaged relationship with East Timor and it will give Australia stronger moral voice in the wider international arena. It is perhaps a vain hope, though, that it will also become a bipartisan position.

- Damien Kingsbury is Professor of International Politics at Deakin University. He has written extensively on East Timor politics, and is married to East Timor’s Honorary Consul in Victoria, Rae Kingsbury.