Thanks to young people, especially those of color, this time might be different.

Emma Gonzalez’s remarkable poise was one revelation of Saturday’s march. I met her before it began, in the press tent, where she broke into a smile listening to the pre-march music playlist. “Yes! I got Celia Cruz on this!” Nodding to the beat, she fielded questions from a dozen national reporters. About the flurry of inadequate but promising gun-safety measures passed since Parkland, she says: “It feels like: they tried to take a giant step—and then they tripped. I’m not gonna knock it, it’s a good first start.” That’s the kind of “we’ll get ’em next time” equanimity activists normally take years, or even decades, to perfect.

The movement, Gonzalez tells reporters, “is probably gonna be years, and at this point, I don’t know that I mind. Nothing that’s worth it is easy. We’re going against the largest gun lobby. We could very well die trying to do this. But we could very well die not trying to do this, too. So why not die for something rather than nothing?”

On that note, a media minder whisked Gonzalez away, as fellow student David Hogg, another movement star, approached. Hogg, 17, wore a stone-colored suit and an earpiece. Then he was whisked away, too; the program was about to begin.

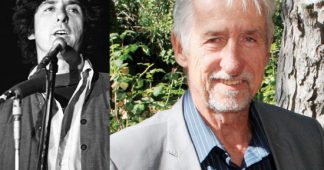

“Damn,” said Vanity Fair writer Dave Cullen. We agreed: We should have ignored the rules and pressed up to where the networks were situated, to talk to Hogg. But Cullen will get his time. This is his story. I decided to trail him, as he tried to trail the Parkland students around Washington, because we have a history on this issue: On April 20, 1999, he called me at Salon, with reports of a school shooting at nearby Columbine High School. He filed almost daily for a while, absorbing the pain of the families and the survivors. Ten years later, he wrote the remarkable bestseller Columbine.

Full disclosure: Since that time, we have become friends. And I’ve watched as he’s gotten calls over the years, after every school shooting, as he goes on TV, or he writes a story, and sometimes he winds up visiting survivors. And he does it dutifully, but I see how it drains him. On his Facebook page, he regularly commiserates with Columbine survivors over the latest mass shooting—the latest example that the nation learned no lessons since 1999. (For me, the most tragic point of the day was when young Sandy Hook survivors talked about how Columbine survivors sent them an encouraging banner; then they unfurled a banner from Newtown High School to Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School. A special gesture, but can’t we just stop this particular kind of brotherhood right here?)

But Parkland hasn’t drained Cullen; it’s energized him. “This is completely different. I swore I’d never come back to a scene [of a mass shooting],” he told me. “But this isn’t about just their grief, horror, pain, and sadness. This is about doing something.” When he wrote Columbine, he worked hard to make it roughly half about the victims and survivors, half about the killers. “But 90 percent of the questions I get, everywhere, are about the killers,” he tells me. “I really thought it was a lost cause, to focus these stories on the survivors.”

But Parkland “flipped the script,” he said. So much so that, strolling through an airport recently and seeing a story about the killer, “I realized I forgot his name!” With the survivors’ activism, he says, “I can cover this story all day and just be energized.”

The second revelation of the day, for me, is how hard the Parkland students have worked to meld their cause to the cause of young black people, who disproportionately suffer gun violence. I met Curtis Kelly, the father of 16-year-old Zaire Kelly, shot during a robbery in Washington, DC, last year as he was coming home from a college prep class. He says the Parkland students have been working with students at Kelly’s Thurgood Marshall High School; his son Zion Kelly, Zaire’s surviving twin, spoke at the rally.

Zion got choked up talking about his brother. “Can you imagine what it’s like to lose someone that close to you?” The students on the stage cheered him on, as his father hugged one of the many friends who’d come out to the event. I have not done the kind of reporting that would let me say with certainty that the Parkland movement—and it is a movement—has done all it can to bring in gun violence victims of color. But Cullen says “behind the scenes,” that’s how many of the Parkland survivors spend much of their time. “They really see the bigger picture. They know there’s more power if they join forces with kids from Chicago, and everywhere—that’s where victory is.”

Certainly the diversity of speakers was impressive—no more than when Parkland survivor Jaclyn Corin introduced a surprise guest: Yolanda Renee King, the 9-year-old granddaughter of Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Looking eerily like her grandfather, she led a chant, smiling and cheering, “Spread the word! Have you heard? All across the nation, we are going to be a great generation!”

I’m not capturing enough of the humor of the rally. My favorite sign was “When They Go Loesch, We Go High,” mocking the NRA’s creepy martinet Dana Loesch. She featured in a lot of the videos produced for the march; her cruel jabs at this movement have made her a justified target. I saw several different posters that featured Michelle Obama in a sleeveless dress with jokes about how hers are the only “guns” we want to see. Amen. “NRA: Lick Our Musket Balls” stays with me, even though I didn’t write it down.

When the program was over, people milled about, almost as if they didn’t want to leave. I met Winston Peraza, an advertising executive from Tulsa, Oklahoma, who had come to support his old friend Manuel Oliver, father of Joaquin Oliver, a Parkland basketball player who lost his life February 14. Peraza wore a “Change the Ref” shirt, one of so many signs and shirts and swag at the march that pointed to the way our political system is controlled by referees “who’ve been paid by the other side,” he said.

And again I ran into Parkland resident Debbi Schapiro, who had worried that Emma Gonzalez’s six-or-so-minutes of silence represented trauma, not a deliberate message. She seemed relieved it was over. “It was phenomenal; it went straight to the heart,” Schapiro said. “We are a broken community. One that is going to band together. But we are truly broken.”

I remind Schapiro that she first thought Gonzalez’s silence represented anxiety, that she had taken on “too much.” She tells me: “It is too much. They’re children. I mean, they chose to do this. But they’ve lost their childhoods.”