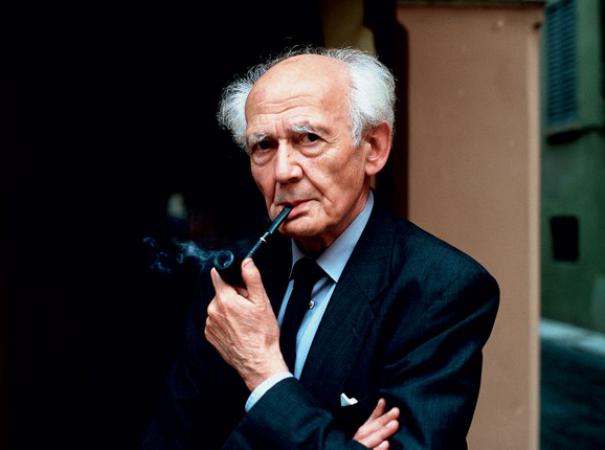

By Paolo Gerbaudo

The 2011 square occupations have been a watershed moment that, despite its evanescence, has profoundly changed grassroots and institutional politics.

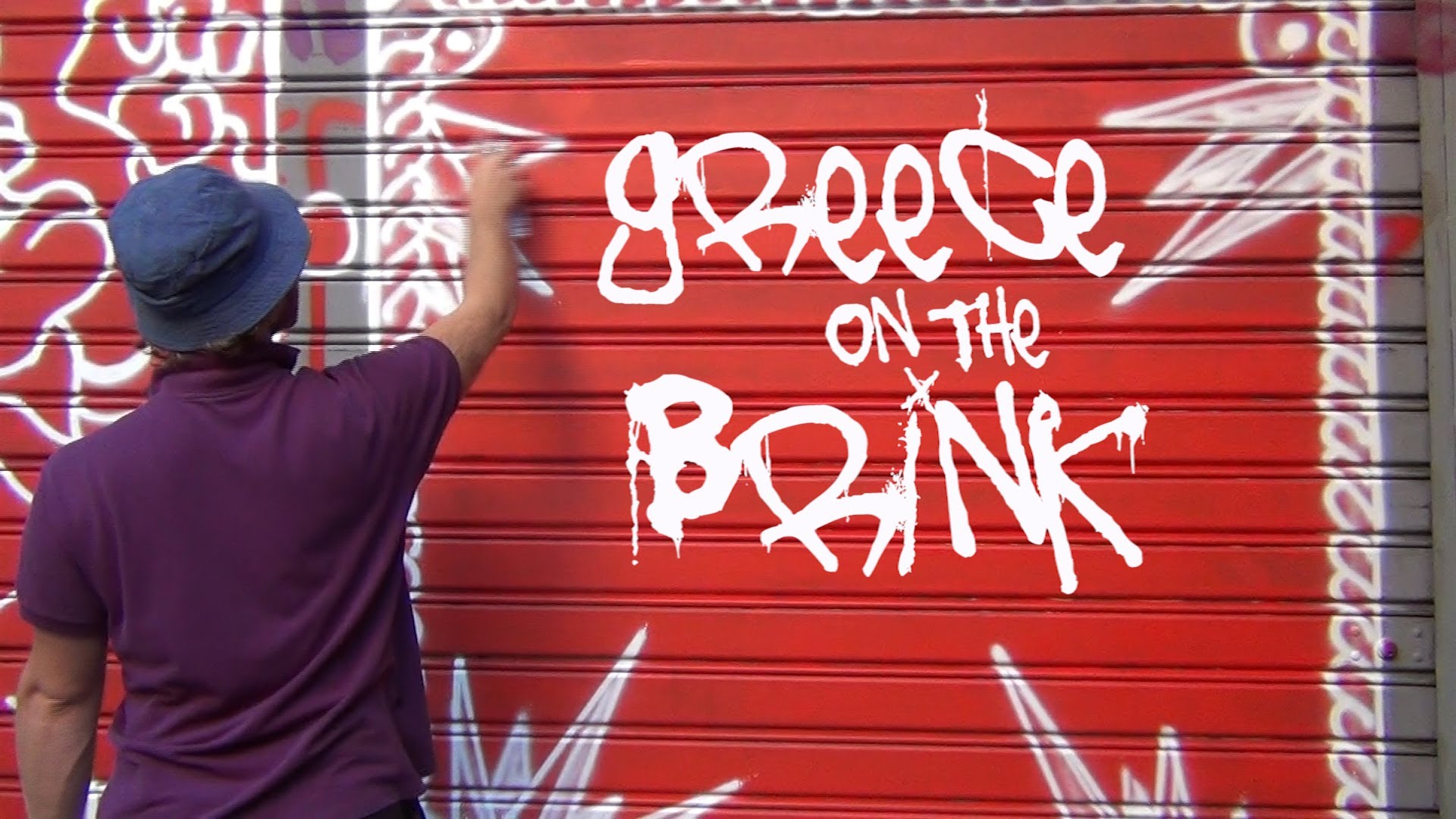

What has become of the great promise of social change raised by the “movements of the squares” of 2011? What did those spectacular occupations of public squares, from Tahrir in Cairo to Puerta del Sol in Madrid and Syntagma in Athens leave behind? To what extent did they contribute to advancing the cause of the “99%” or of the “common and ordinary people” they purported to fight for?

With protest movements, as with any other social and political phenomenon, there comes a time to take stock of what has happened — a time that is as important for evaluating the past as it is for planning future action. The latter appears to be particularly relevant in light of the rise of new movements, such as Nuit Debout in France, that can be seen as the continuation of the 2011 cycle.

Five years since 2011, famously celebrated as the “year of the protester” on the annual cover of TIME Magazine, we are perhaps sufficiently distant from the heat of those events to draw up something akin to a balance sheet of the achievements and letdowns of that momentous wave of protest.

The appraisal of the mobilizations of 2011 is, as it often happens with great historical events, a highly contentious topic. The movements of the squares have enthused in equal measure as they have disappointed; they have both under-delivered and over-delivered.

For some people these protests seemed to have achieved nothing at all; for others, like the Greek activist Giorgios Giovannopoulos, they “completely changed the political landscape.” Some, including many nostalgic leftists, see them as just a distraction from serious politics,or a childish display of naivety; for others, the mobilizations have been a decisive turning point in contemporary politics.

Read the full article here:

https://roarmag.org/essays/2011-balance-sheet-paolo-gerbaudo/